Villages without power supply are easy to find though the government says there are none. The lines are laid, but many villagers are too poor to pay for electricity. BPL (below poverty line) families, entitled to free supply, are waived the installation charge. But they don’t have money to wire their homes. Others are held back by the fear that bills will rise beyond reach.

“Electricity is like a star,” says Vinod, a barber who also works as a farmhand. “Everyone wishes for it, but few can afford it.”

He knows that well: it’s only a couple of months since electricity arrived at his home in Uchauli village, Hardoi district, some 70 km from Lucknow. In May 2017, the government declared that the village had been electrified. But only a few signed up for connections. Villagers and voluntary groups say officials denied people like Vinod a free connection, saying they weren’t on the BPL list.

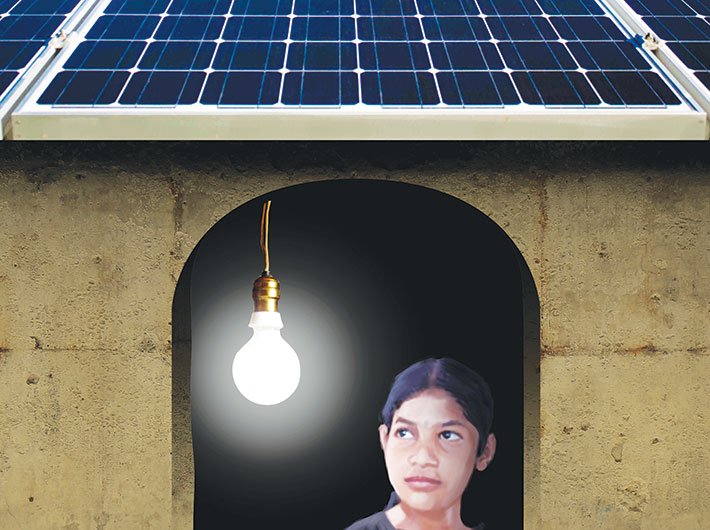

The solar panels and supply grid set up by HCL as a CSR initiative in Uchauli, Hardoi district, Uttar Pradesh. The IT giant has set up such grids in 13 villages of the district.

It isn’t as if Vinod suddenly found the money to buy electricity. Thanks to Samuday, a corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative of IT giant HCL, he gets it free. In October 2018, Samuday offered them electricity from a solar grid and promised fixed hours of supply at prices reached by consensus. The villages responded enthusiastically: 120 of the 182 households enrolled, though the installation charge was only a rupee cheaper than the government’s charge of Rs 500. Forty houses having government connections signed on for the solar-grid project as a fallback.

What won them over was Samuday’s collaborative, pragmatic approach. Navpreet Kaur, director of Samuday, says it took time to convince the villagers. “They had accepted lack of electricity as a fact of life. They were also ignorant of how electricity could change their lives. We organised meetings involving men, women, village elders, the pradhan. People had assumed that bills would shoot up after five or six months. But we told them they would themselves calculate and set the tariff based on the appliances each household used. They were finally convinced.”

The project took about two years: surveys had to be conducted, village-level committees had to be formed, operational set-ups had to be designed and implemented, solar panels and grid lines had to be installed. Kaur says the team strove to arrive at affordable pricing.

“If you distribute something for free, nobody values it. We want villagers to bear the basic maintenance cost. They should not depend on us. Right now, we supply power for eight hours daily. At the base price, every house gets to run two LED lamps. If someone wants to run a fan, a refrigerator, a TV set or other things, the bill goes up accordingly,” she says.

The Samuday team reached out to those who did not enroll despite the village-level meetings. “We checked out their financial condition, and for people like Vinod, who really couldn’t afford it, we installed meters free of cost,” says Kaur. The team also electrified the local health centre and schools. They don’t have to pay for electricity.

Samuday has installed 13 solar grids in Hardoi district: besides Uchauli, the villages are Kantha, Dugnai, Dhautera, Tutiyara, Samuda-Tajpur, Fatehup, Darshankhera, Bhiri, Malhpur, Gujrehta, Basantpur, and Mavaee. They generate 302 KWs and power some 2,000 households and 215 street lights, besides health centres, schools and other facilities. All grids will eventually be managed by the villagers.

“Solar grids are the way forward, as coal-burning plants pollute,” says Kaur. “India has committed to producing 30 percent of its electricity needs from renewable sources by 2030, and electrifying villages with solar energy is one step towards achieving that goal.”

Many villagers are acutely aware of how cities have better government-supplied amenities. Shivrani, a 62-year-old widow who lives in Malhpur village, says, “In 2014, I lived with my youngest son in Noida for one month. He gets electricity for 18-22 hours a day. For urban people, it’s considered a basic need; for us, it’s considered a privilege. I always wanted electricity in my village.”

Boardly speaking

Outside every village recently electrified by the government, there are boards such as this one. They declare that the village has been electrified under the Pradhan Mantri Sahaj Bijli Har Ghar Yojana (also known as Saubhagya) or the Deen Dayal Upadhyay Gram Jyoti Yojana. This board is in a village in Uttar Pradesh, a state in which the government claims all 74.78 lakh homes have power supply. What many boards, like this one, really say is that electricity has been brought to the village and that “those interested” in signing up have been provided electricity. Affordability, encouraging villagers to sign up by offering incentives – alas, the government mechanism rarely works with sensitivity that will consider those questions.

Her house, where she lives alone after her three sons left to work in cities, is made of bricks plastered with mud. The roof is covered with tarpaulin to prevent leaks during the rain. A chulha, some clothes, a few utensils – she owns little. But when Samuday approached her, she readily signed on. (In fact, all 152 households in Malhpur signed up.)

“The government definition of power supply is vague. They promise wires, poles, bulbs, meters...but not proper supply. Samuday provides fixed and guaranteed power supply. This brightens the future of our children,” Shivrani says.

It also fosters self-reliance. Says Samuday head Kaur, “We want villagers to take responsibility for the solar grids. The life cycle of the batteries is 5 years, though the solar panels have 25-year warranties. We have estimated the household needs in these villages for the next 25 years. Schneider Electric, who set up the grids, trained village youths in maintenance, repair, etc. When we leave, we want people to take ownership of the grid.”

(This article appears in the February 28, 2019 edition)