Why the Nasreen Rehman translation promises to be the definitive English edition of the ultimate ‘readers’ writer’ of the subcontinent

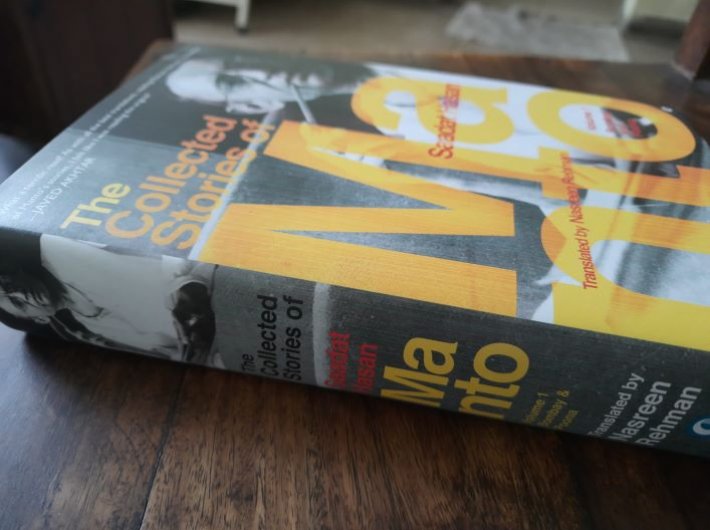

The Collected Stories of Saadat Hasan Manto: Volume 1: Bombay and Poona

Translated by Nasreen Rehman

Aleph Book Company, 548 pages, Rs 999

There are writers, there are writers’ writers, and then there are readers’ writers. Saadat Hasan Manto is one of the rare few in the third category. His short stories continue to appeal to the widest possible range of readership. The kind of people who otherwise don’t find reading books worth bothering would make an exception for some writers. Manto, along with Premchand, is among them in this subcontinent.

Manto (1912–1955) was, in a way, continuing the great tradition of the nineteenth-century fiction – he is said to have begun his literary career by translating a Victor Hugo novella. Like Chekhov, he is interested in reproducing in words the lived lives of a larger class of people, as opposed to ideas and isms of the elite. A single theme runs through his twenty-odd collections of short stories apart from his plays, radio dramas, screenplays and some essayish prose pieces: he was equal parts curious and sympathetic about the dramatic points of common folks’ lives.

In the old parts of a city – Delhi, Lucknow, Lahore – or towns, among the people of a certain generation, it won’t be out of place to come across those who narrate the gist of stories like ‘Toba Tek Singh’, ‘Thanda Gosht’, ‘Khol Do’ or ‘Kali Shalwar’ as if they were narrating some factual, historical anecdotes. And many of them need not have read the stories themselves; they might have only heard them.

The period in which he was writing was a historically defining one for India and Pakistan, and that makes his stories an archive of a unique kind. Partition of India, a great calamity, inspired countless works of fiction and memoirs, but Manto’s stories shine light on personal tragedies, ironies and the ‘banality of evil’ like no other work. He bears witness but in his own idiosyncratic way.

That explains why Manto’s appeal is not restricted to the common readers and why a pre-eminent world historian like Christopher A. Bayly would be fascinated by Manto’s tales.

It was Nasreen Rehman, working on her doctoral dissertation, ‘A History of the Cinema in Lahore, c. 1919-1947’, who had selected and translated fifteen Manto stories for Bayly, who was her thesis supervisor. “A generous teacher with a singular ability to immerse himself in a student’s work, Chris read the stories and, encouraged by him, I used Manto as an ethnographer in my thesis,” writes Rehman.

That was years ago. After a career in private and public sectors in the UK and Pakistan as an economist, Rehman turned to the arts and humanities. It was the urging of Aleph Book Company founder David Davidar that she took up the mammoth project of putting together all of Manto’s 255 known stories translated into English for the very first time.

The first volume (‘Bombay and Poona’), published this month, includes fifty-four stories and two essays written when he lived in those two cities and worked in the film industry there. It features well-known stories like ‘Mummy’ and ‘Janki’, which provide rare insights into the Poona film industry; the fascinating story of ‘Babu Gopinath’; and ‘My Marriage’ and ‘My Sahib’, two essays that read almost like stories.

There have been several translations of Manto’s works, but usually under the rubric of ‘best-of’ or on the theme of Partition, if not in bits and pieces. The Aleph series promises an exhaustive, comprehensive collection. While for Manto fans, it is a moment of celebration, it is also an ideal entry point for new readers. For the either kind of reader, the USP of this volume has to be the long introduction from the translator. It is the story of a character called Manto, his life and history-making times.