India is facing its ‘worst’ water crisis in history, according to the government’s think-tank NITI Aayog’s Composition Water Management Index (CWMI) report. Moreover, by 2030, the country’s water demand is projected to be twice the available supply. The study also states that 21 cities, including Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad, will run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting 100 million people.

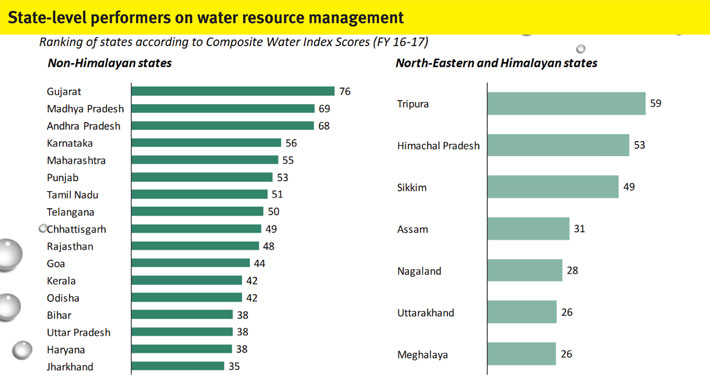

The CWMI report has ranked all the states in India on the basis of their composite water management. Gujarat has topped among states in efficiency of water management in 2016-17, followed by Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra. The ‘low performers’ are the populous northern states including Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan, which are home to over 600 million people or half of the country’s population. Among the northeastern and Himalayan states, Tripura is at the top position for effective water management in FY17 followed by Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Assam.

However, there is large inter-state variation in water index scores, and most states have achieved a score below 50 (out of 100) and need to significantly improve their water resource management practices.

What can be done: Some CWMI recommendations

- The Composite Water Management Index can establish a public, national platform providing information on key water indicators across states. This platform will help in monitoring performance, improving transparency, and encouraging competition, thereby boosting the country’s water achievements by fostering the spirit of ‘competitive and cooperative federalism’ among the states. Further, the data can also be used by researchers, entrepreneurs, and policymakers to enable broader ecosystem innovation for water in India.

- Explore incentive-based mechanisms for groundwater restoration, such as an innovative water impact bond that pays out funds to community organisations/ NGOs on achieving groundwater recharge targets.

- Currently, water is a state subject, resulting in frequent inter-state disputes and limited policy control by the centre. Further, funding to states is not linked to performance to water metrics. A National Water Fund may be established under which the centre can bypass the state list issue and incentivise adherence to national policy guidelines by providing funding for water infrastructure and conservation to high performing states.

- Geo-tagging and the construction of harvesting structures.

- The government can improve the country’s water-efficiency in agriculture by accelerating the proposed DBT scheme for micro-irrigation subsidies. In this way the market competition and innovation can bring down the equipment cost and enable greater adoption.

- At present India treats only 30% of its water and reuses a negligible amount. The country needs to establish a network of treatment plants and piping infrastructure to treat domestic waste water and put it back into the supply system for reuse in domestic consumption and peri-urban agriculture irrigation.

- Currently, water data either does not exist, is unrealiable due to outdated methodologies, or is not shared across all policymaking levels. By establishing a central platform for surface water and ground water data across a variety of parameters, the government can improve policymaking at all levels and enable innovation through open APIs.