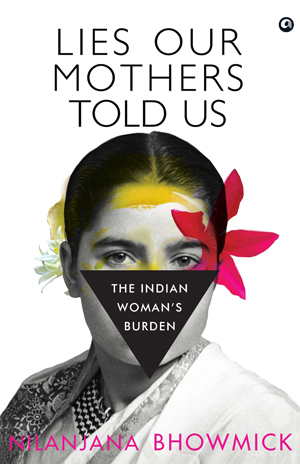

An excerpt from Nilanjana Bhowmick’s ‘Lies Our Mother Told Us: The Indian Woman’s Burden’

Lies Our Mother Told Us: The Indian Woman’s Burden

By Nilanjana Bhowmick

Aleph Book Company / 272 pages / Rs 699

Savitribai Phule, Mahasweta Devi, Amrita Pritam, Medha Patkar, Kamla Bhasin, and countless others have, since the nineteenth century, fought for and won equal rights for Indian women in a variety of areas—universal suffrage, inheritance and property rights, equal remuneration, prevention of sexual harassment at the workplace, and others. Pioneering feminists believed that due to these hard-won rights, their daughters and granddaughters would have the opportunity to have rewarding careers, participate in the social and political growth of the country, gain economic independence, and become equal partners in their marriages. On paper, it would appear that the lot of Indian women in the twenty-first century has vastly improved but, in reality, the demands of capitalism and the persistence of patriarchal attitudes have meant that they continue to lead lives that are hard and unequal, especially when compared to their male counterparts.

Savitribai Phule, Mahasweta Devi, Amrita Pritam, Medha Patkar, Kamla Bhasin, and countless others have, since the nineteenth century, fought for and won equal rights for Indian women in a variety of areas—universal suffrage, inheritance and property rights, equal remuneration, prevention of sexual harassment at the workplace, and others. Pioneering feminists believed that due to these hard-won rights, their daughters and granddaughters would have the opportunity to have rewarding careers, participate in the social and political growth of the country, gain economic independence, and become equal partners in their marriages. On paper, it would appear that the lot of Indian women in the twenty-first century has vastly improved but, in reality, the demands of capitalism and the persistence of patriarchal attitudes have meant that they continue to lead lives that are hard and unequal, especially when compared to their male counterparts.

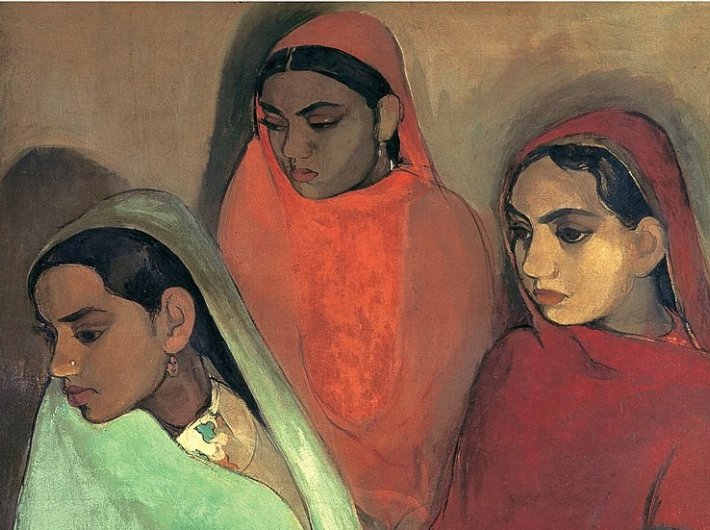

Indian women are among the most overworked in the world—they spend on average 299 minutes on housework and 134 minutes on caregiving per day, shouldering 82 per cent of domestic duties. They are burdened with work from such a young age that many are forced to drop out of schools, leave the labour force, and give up dreams of financial independence. For those who have the privilege of choosing to have a career, the only way they can make this viable is by doing the ‘double shift’: women are expected to do most of the housework, childcare, and caregiving, whether they have jobs or not. While these problems apply to all women across the country, those in India’s middle class face an altogether unique challenge because middle-class families have mastered the art of simulating an environment of empowerment in their homes. 'Lies Our Mothers Told Us: The Indian Woman’s Burden' takes a close look at the gender inequality that forms the bedrock of India’s middle class—this forces women try and be ‘superwomen’ while ignoring the deleterious effects on their mental and physical health. Using available data and anecdotal evidence from the real lives of Indian women across the country, journalist Nilanjana Bhowmick asks if, in our patriarchal society, the assertion that ‘women can have it all’ comes at too high a price.

Here is an excrpt from this work on the occasion of International Women's Day:

I clearly remember the day when my father had taken my sister and me out for a stroll and we met an acquaintance of his. My father introduced us to him. It was probably the look of pity on the acquaintance’s face, the unsaid exclamation—What a disaster! Two daughters!—that prompted my father to say, ‘They are like my sons.’ He did the best he could but even so he unconsciously killed a little light in me. He always called me his son—I didn’t want to be like a son. I wanted to be the daughter I was. It was a stark portent of what I would be fighting against throughout my life. ‘One of the women in our communities shared a story that when you do something really impressive, like doing well in school or something, and parents would use the phrase “you are like a son to me”. What was more interesting is that when the woman shared that story, it really resonated in the group. And I was so struck by that because we know biases start young, but to hear from your parents when you do something amazing that you are a son to them, it was a very interesting marker from a cultural standpoint as to how rigid gender roles were here,’ Rachel Thomas, co-founder of the Lean In organization with Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, told me. The Lean In organization runs circles in 174 countries across the world, including around 890 in India. These circles are support groups for working women and women who want to get back to work after having children. The stories in these circles had introduced Thomas to the startling gender biases in India.

But there are other kinds of biases in India, too. Biases of height, weight, complexion—too tall, too short, overweight, underweight, dark complexioned—affect a woman’s prospects in life. A friend in college was married off when she was only nineteen because she was ‘too tall’ and her parents were anxious they wouldn’t be able to find a suitable groom for her when she was older. She was a good student with a great academic future. She wanted to be a university professor. But for her family—upper caste, upper middle class, wealthy, and highly educated professionals—her future would begin and end with a good marriage. She did manage to continue her education after her marriage, but every time I met her or spoke to her after her marriage, I found her distracted and sometimes listless. The girl who had wanted to become a professor of English literature, ended up teaching in a private school. When I met her after many years, she told me, ‘Teaching in a school suits me. It allows me to look after the home and my children.’ By then she had two daughters.

Teaching, especially in private schools, is a popular profession among women in India because it seemingly does not place high demands on their time (events, late nights, night shifts) and allows them to balance home and work effectively. It is often equated with being a feminine job, a job that requires caring for children and, hence, something that many career-minded young women are nudged towards by their families. Additionally, it is not a high-growth job in this country and often does not require one to be highly skilled. While government schools do require applicants to have certain qualifications and to give entrance tests, low to mid-level private schools often circumvent such requirements. A 2018 study by the Azim Premji Foundation found that private schoolteachers had low academic qualifications, and scant or no professional training and experience as educators.4 Interestingly, in public schools, where 90 per cent of the teachers were graduates, 98 per cent were professionally qualified and had taught over 160 months on average, most of the teachers were men. It should be noted that government school jobs are more secure and come with varied benefits as well as job security whereas private schools (as I have seen among my friends who are teachers) pay a much lower salary with less job security and longer working hours. Female teachers mostly taught in private schools where 76 per cent of the teachers were graduates, and 64 per cent were professionally qualified. In these schools, the average experience of teachers was seventy-four months.

But while teaching allows women more stable hours, it also kills any other ambitions they might have. Divya [named changed] was moving up in the corporate world when she had to hit pause to prioritize her two young boys and her husband’s various job postings. When she stopped, she was working at a multinational company and earning more than her husband. She had deliberated staying behind in Delhi to keep her job but then she gave in to pressure from friends, neighbours, and family—how could she separate the family? She freelanced for a while before giving it up all together. When she eventually returned to full-time employment owing to an unforeseen misfortune, the only job available to her was that of a teacher. It was the only job that gave her the time to balance all her housework and caregiving duties with her professional commitments. She compromised, she adjusted, she reinvented herself. That’s what women do constantly. She had learnt early on that true happiness was a mirage, that we have to work with what we have. And that’s exactly what she did.

Overwork—or unpaid labour, if you prefer—is something every girl grows up negotiating right from her childhood. The constant devaluation of their capabilities and the constant over-evaluation of men’s abilities manifests itself in all gender-related social ills in our country. The thinking that women and girls are only good for reproductive labour means that many are pushed into becoming wives and mothers before the time is right, before their bodies and minds have completed the transition into adulthood.

[The excerpt reproduced with permission of the publishers.]