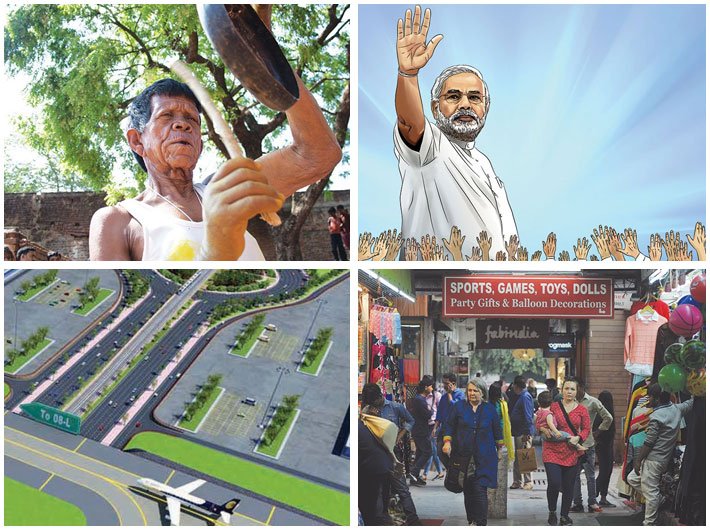

People who have known the prime minister up close say his magic – which according to analysts handed the BJP a landslide victory in Uttar Pradesh despite anger over demonetisation – is not all about charisma: it emanates from his good habits of working hard, being a keen listener, taking every issue seriously, and openness to new ideas, which he refines to perfection. There’s no place for courtiers to hang around the tall and seemingly aloof figure of Modi. “He gives 100 percent attention to you while discussing an idea,” says a BJP leader. He is privy to an incident in which Modi sat for one and a half hours with an undersecretary-level official, listening to his ideas about changing India.

By all accounts Mumbai is a high-flying city. Except on one. It just doesn’t have enough land to, well, safely land the ever-growing tribe of globetrotters. The city is adding close to six million air passengers every year. That’s a Singapore taking off or landing in Mumbai every year. For the record, 41.67 million passengers used the Mumbai airport in 2015-16, and that figure is expected to breach the 46 million mark by the time this fiscal year winds down to an official close. More and more people flying in and out of a city is usually good news. But this is Mumbai, a city where holding on to land is a harder fought battle than some of the high-flying boardroom skirmishes. The Mumbai airport has decisively lost one battle at least, if not the war.

Twelve years after announcing the elimination of leprosy, the government is undertaking a massive vaccination drive against the disease. That slow about-turn is the culmination of a rush to meet a statistical goal and, in the process, the casting aside of the creation of a Padma Bhushan awardee. Dr GP Talwar, a sprightly 91 years, keeps a regular 10-to-6 schedule at the Immunology Foundation, in Neb Sarai, Delhi. It’s an independent not-for-profit, where he directs doctoral and post-doctoral work. “In 1969-70, when I was at the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), the World Health Organisation (WHO) approached me to work on a vaccine against leprosy,” says Dr Talwar, who later became the founding director of the National Institute of Immunology (NII), Delhi.

An archetypal Indian, let us call him Ram Lal, pays water tax, municipal tax, road tax, house tax, sales tax, central sales tax, professional tax, value added tax, octroi, service tax, excise duty, customs duty and myriad other taxes. Then, on whatever money is left with him, Ram Lal has to pay income tax. Ram Lal has also to pay a number of cesses and duties – education cess, krishi kalyan cess and Swachh Bharat cess to name a few. No wonder Ram Lal feels short-changed when he sees Bharat getting dirtier, roads developing newer potholes, farmers committing suicide and the number of illiterates rising. To collect all these taxes, the centre, states and municipal corporations have full-fledged tax departments which have full authority in law to enforce their just and unjust demands.

In the nine years of my career here, I have not seen a single instance of a couple bringing along a relative who will bear their child as a surrogate mother,” says Inderpreet Kaur, head coordinator at Baby Joy, a west Delhi-based clinic that provides in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and surrogacy services to childless couples. Doctors and administrators at hundreds of infertility clinics across the country will second Inderpreet: in India, it’s almost unheard of for a surrogate mother to be related to the couple seeking treatment. But the draft Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, introduced in Lok Sabha last November, proposes to change that drastically – and, some would say, impractically. If passed, it will only allow a relative of a couple to bear a child for them. It will also ban commercial surrogacy, that is, paying a woman, usually poor, to bear a child for a couple.