A senior bureaucrat, apparently much respected among the administrative circles, faces two years in jail. His crime: a decision that may have come from the political leadership.

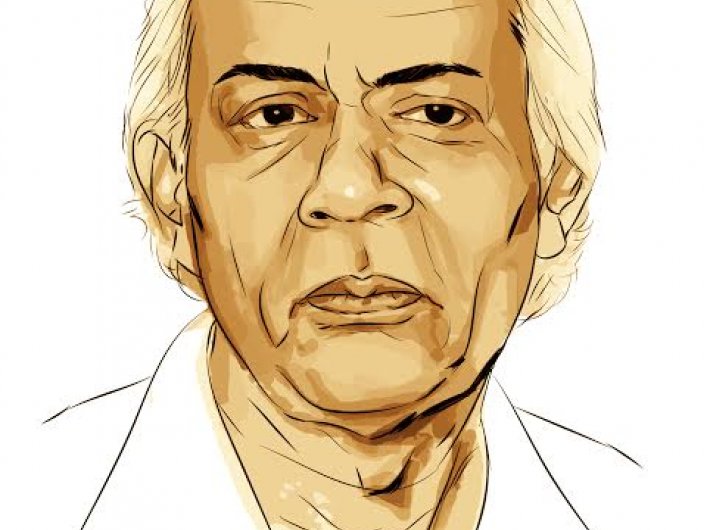

HC Gupta, a former coal secretary, is among the three bureaucrats convicted by a special court in a coal block allocation case. They have been slapped with two years in jail and a fine of Rs 1 lakh each, though court has granted them bail to appeal in the Delhi high court.

CBI had charged Gupta with presenting false information before the minister – prime minister Manmohan Singh was holding the charge of the coal ministry back then.

The court had last week convicted Gupta, KS Kropha (then joint secretary in the coal ministry) and KC Samaria (then director, coal allocation- i section of the ministry) of criminal conspiracy and cheating under the Indian Penal Code and for corruption under the Prevention of Corruption Act.

There are two issues at stake here: one, the responsibility of the bureaucrat in executing what may essentially be a political call, and two, the pending bill to amend the Prevention of Corruption Act which, among other things, aims to provide relief to bureaucrats in such circumstances.

As Mukul Sanwal, a former secretary to the government of India, explained in his

column in

Governance Now, the definition of corruption in Section 13(1)(d) of the existing PCA covers various indirect forms of corruption including the obtaining of “any valuable thing or pecuniary advantage” by illegal gratification or by “abusing his position as a public servant”. The section defines “Abuse of Official Position” under the overall category of “criminal misconduct by a public servant”. The amendment bill replaces this section with a definition of criminal misconduct by a public servant in terms of fraudulent misappropriation of property under one’s control, and intentional, illicit enrichment and possession of disproportionate assets.

“Currently, an investigating officer has only to establish that legal provisions, guidelines and rules were violated which led to pecuniary advantage to somebody, including a third party, and not necessarily the public servant. There is no requirement to prove a direct trail of money, or any other quid pro quo, with respect to the public servant in the decision-making process.

“This anomaly of treating administrative decisions as part of a criminal conspiracy is now sought to be rectified in the amendment to the PCA recently approved by the select committee of the Rajya Sabha. It conforms to widely accepted international practice and is far from being a conspiracy of the ‘political establishment’ reflecting the ‘power of babudom’,” writes Sanwal.

The amendment bill has been subject to much debate, especially for the shield it offers to the bureaucrats. “The bill has replaced the definition of criminal misconduct. It now requires that the intention to acquire assets disproportionate to income also be proved, in addition to possession of such assets. Thus, the threshold to establish the offence of possession of disproportionate assets has been increased by the bill,” explains the PRS Legislative Research in its

analysis of the bill.

This necessity arose in the scam-a-day times of the UPA regime, when bureaucrats were perceived to be afraid of taking administrative decisions, leading to what was called policy paralysis.

On the other hand, a section of anti-corruption activists has opposed raising “the threshold to establish the offence”, as it may weaken the fight against graft – even if Gupta’s case seems one of a kind.

One way out, arguably, is what Sanwal advocates: “The problem in dealing with it is not the revival of the ‘single directive’, requiring prior approval of government or Lokpal to initiate an inquiry into allegations of corruption against public servants. The real problem is the focus on a single definition of corruption unrelated to criminality, the organisational context ignoring the many ways corruption now takes place and the enforcement model.”