A new law correctly distinguishes between bribery and misconduct. But what is lacking is a broader approach to tackling corruption, and a new model for enforcing the law

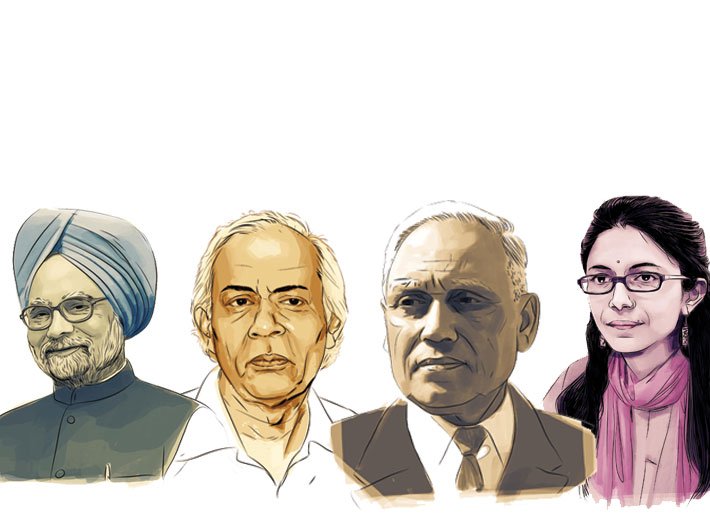

There is a common thread between the charges of alleged corruption CBI has filed against former public servants – Manmohan Singh (prime minister), Harish Gupta (secretary, coal), Shashindra Pal Tyagi (air chief marshal) – and by the anti-corruption bureau of the Delhi government against Swati Maliwal (chairperson, Delhi commission for women). In each case the investigating agency has failed to show when and how much bribe was paid.

Definitions

The Prevention of Corruption (Amendment) Bill, 2013, to amend the Act of 1988, is pending before parliament. This bill was first introduced in the Rajya Sabha in 2013, during the UPA regime and further amendments were proposed by the NDA government in 2014. A select committee of the Rajya Sabha, comprising members from across the political establishment, has approved these changes which have been endorsed by the cabinet.

The definition of corruption in Section 13(1)(d) of the existing PCA covers various indirect forms of corruption including the obtaining of “any valuable thing or pecuniary advantage” by illegal gratification or by “abusing his position as a public servant”. The section defines “Abuse of Official Position” under the overall category of “criminal misconduct by a public servant”. The present bill removes this section and replaces it with a definition of criminal misconduct by a public servant in terms of fraudulent misappropriation of property under one’s control, and intentional, illicit enrichment and possession of disproportionate assets.

Currently, an investigating officer has only to establish that legal provisions, guidelines and rules were violated which led to pecuniary advantage to somebody, including a third party, and not necessarily the public servant. There is no requirement to prove a direct trail of money, or any other quid pro quo, with respect to the public servant in the decision-making process.

This anomaly of treating administrative decisions as part of a criminal conspiracy is now sought to be rectified in the amendment to the PCA recently approved by the select committee of the Rajya Sabha. It conforms to widely accepted international practice and is far from being a conspiracy of the “political establishment” reflecting the “power of babudom”.

Worldwide, anti-corruption laws do not criminalise breaches of duty; rather they seek to prevent it by criminalising bribery which is likely to encourage breaches of duty. The law commission also suggested that any “undue advantage” that results from “improper performance of public function or activity” of a public servant should be punishable. Clearly, the focus has rightly to be on ‘undue reward’ and not the process of decision-making. Adherence to guidelines and rules is the domain of the CAG and has unfortunately become the basis of charge-sheets filed by the CBI in cases of alleged corruption.

The proposed amendment clarifies the law by defining criminal misconduct in terms of financial gain to bring it in line with international practice limiting corruption to bribery. Including bribe-givers is an important step forward to ensure that senior corporate actors are sufficiently accountable.

Public servants are justifiably concerned about ex-post-facto review of decision-making by an investigating officer and a criminal court. The law as it stands also includes concepts such as “abusing his position as a public servant” which have broad interpretations. Both criminalise matters which should be inquired into only as misconduct. The Prevention of Corruption Act currently confuses misconduct with corruption.

Enforcement model

The debate should really be on the approach to corruption responding to changed conditions since the anti-corruption legislation was first framed in 1988, in five key areas.

First, cases involving decisions by Ministers should be considered by a tribunal set up on the lines of the French Court of Justice of the Republic. It is made up of three judges and six lawmakers from both the lower and upper houses of parliament, gives its ruling in seven days and does not preclude a separate criminal investigation.

Second, dealing with “corrupt or other improper exercise of police powers and privileges” should be based on a new offence of police corruption, on the lines of legislation in the UK. It covers cases in which a police officer acts improperly with a view to obtaining an advantage for themselves or someone else – or causing some form of detriment to someone else, “fails to act” for a corrupt purpose, and it would also apply when an officer threatens to do something, or not do something, for an improper purpose. This flows from an analysis of the criminal justice system where individuals corrupt staff and processes to avoid arrest, prosecution and conviction.

Third, demonetisation highlights that money laundering is now the most significant form of corruption. It cannot function without access to the legitimate economy to launder illegal gains through the financial sector, or use the services of lawyers or accountants to invest in property or set up front businesses. A small number of corrupt or negligent professional enablers, such as bankers, lawyers and accountants can act as gatekeepers between the corrupt, and organised criminals, and the legitimate economy and should face heavy criminal sanction, for which a new offence needs to be formulated, as well as a new enforcement model.

While India has taken steps and widened the definitions under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act in 2012 (the law was enacted in 2002) to align with international laws related to anti money laundering and counter financing of terrorism, the enforcement model has not changed. A report by the US Department of State titled ‘Country Reports on Terrorism 2015’ said that the Indian government is yet to implement the legislation effectively, especially with regard to criminal convictions. “Law enforcement agencies typically open criminal investigations reactively and seldom initiate proactive analysis and long-term investigations,” it added.

Fourth, corruption in local government needs different treatment through improving transparency. For example, the public should have the right to inspect records of decision-making with respect to planning, land development, housing and contracts and suggest matters for audit to inspect. The action taken should be part of the annual report of these bodies. Integrity of institutions in their public dealing needs to be strengthened using digital technology, for example, on the model of reforms for the issue of passports.

Fifth, it is also important to periodically gather and analyse information about the full extent of corruption and institute appropriate measures. This should be done within government as well as with civil society and the public. A web-based reporting mechanism for the public with easier procedures and measures to incentivise and support whistleblowing will be needed.

Corruption is indeed hydra-headed. The problem in dealing with it is not the revival of the ‘single directive’, requiring prior approval of government or Lokpal to initiate an inquiry into allegations of corruption against public servants. The real problem is the focus on a single definition of corruption unrelated to criminality, the organisational context ignoring the many ways corruption now takes place and the enforcement model.

Sanwal is a former civil servant.

(The column appears in February 1-15, 2017 issue)