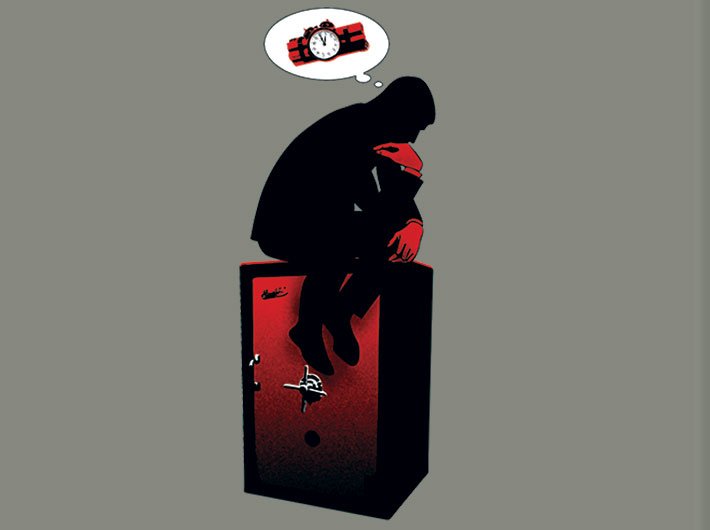

*But were afraid to ask. It is government’s last valiant attempt to bring black money out, and make it productive for economy

Black money, since the colonial times, has been the elephant in the room: it is everywhere and yet rarely talked about. In recent years, however, the middle class has become more strident in demanding action and it has led to a couple of large-scale public agitations. In Narendra Modi’s election campaign too, recovering black money was a much-talked about promise. Closer to the mid-point of its term, the government has attempted to combat the underground economy with the Income Declaration Scheme (IDS), first announced in the budget 2016.

The IDS, closing on September 30, is different from the previous schemes targeting black money in one crucial aspect: it is not an amnesty scheme but the central board of direct taxes (CBDT) is going to levy a total tax of 45 percent including 30 percent tax, 7.5 percent penalty fee and 7.5 percent surcharge. This means that if someone discloses unaccounted income or assets worth Rs 1 crore, Rs 45 lakh – close to half of it – would directly go to the government’s kitty, while the rest would turn into ‘white’. In the past, the maximum tax that the government charged on black income disclosure did not exceed 15 percent.

Read interview with Principal Chief Commissioner of Income Tax, DS Saksena: We cannot afford to do business with black money

Among the incentives under the IDS, no prosecution will be launched under the Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988, the Income Tax Act or the Wealth Tax Act in respect of the assets declared. Declaration made under the scheme will not be admissible as evidence against the declarant under any other legal proceedings. However, no immunity is provided under the Foreign Exchange Management Act, Money Laundering Act, Indian Penal Code, Central Excise Act, Customs Act, service tax provisions, VAT provisions or other Acts.

In his Mann Ki Baat address on June 26, prime minister Narendra Modi said that no one will believe that in a country with population of over 125 crore, only 1.5 lakh people have taxable income of over Rs 50 lakh. “People having annual income over Rs 50 lakh are seen in several lakhs in metro cities… Before the government takes up stringent steps to recover unaccounted money, it should give a chance to the residents and that’s why, my dear brothers and sisters, it [the IDS 2016] is a golden opportunity,” Modi said.

Read interview with Prof Arun Kumar: “But for black economy, each one of us would have been seven times richer”

The scheme was launched on June 1. Since then the CBDT has been putting explanatory notes, audio-visual messages and FAQs on its portal. Officers, led by finance minister Arun Jaitley, are addressing meetings, clarifying confusions. The income tax department is trying to bridge the trust gap with potential taxpayers. All principal commissioners are going in the field, meeting chartered accountants and lawyers, and asking them to convince their clients to disclose their income. After the scheme, CBDT will issue letters to evaders using its database of information on nine lakh high-value transactions.

Column: Time to end the marriage of bad money and bad politics

However, the response so far has been predictably tepid – while a number of officials Governance Now spoke with refused to give the figure of collections so far since it is classified information, a senior official, on condition of anonymity, said, “We have recovered approximately Rs 4,500 crore so far and the total recovery at the end of the scheme may not be more than Rs 10,000 crore.” The official cited three reasons for the lukewarm response:

(a) The tax rate of 45 percent is too high: Through the long-term capital gain tax, people can easily get their black money turned into white by paying just 6-7 percent.

(b) The scheme is not all-inclusive: Those who have already been sent notices by the income tax department are not covered under it.

(c) The lack of any fear of law: When cases go to the tribunal, most of the evaders go scot-free. Also, the prosecution process is very slow.

At the same time, as another officer pointed out, people have a tendency to wait and watch how others are going about it and then make the move; so bulk of declarations are expected only in the final hours on September 30. Meanwhile, the officers said, the department has been receiving a lot of queries.

There has been no extension as far as declaring income is concerned – and the deadline won’t be extended. The department, however, has announced the extension of the last date for paying taxes from November 30 this year to September 30 next year, and the amount can be paid in installments. A minimum of 25 percent of the tax, surcharge and penalty is to be paid by November 30, another 25 percent by March 31, and the remaining amount by September 30.

After the closure of the scheme, the department will take up a major drive to prosecute the evaders. There will be two aspects of it: penalty and prosecution. There is no separate provision under the scheme to punish the evaders, but the Income Tax Act was amended to change the penalty provisions. In case of not reporting the undisclosed income, in addition to the tax, a penalty of 200 percent will be levied.

Some experts have argued, echoing a CAG report of 1997 on the voluntary income disclosure scheme, that such measures to unearth black money are counterproductive, and even discouraging the regular, honest taxpayers. Responding to a public interest litigation (PIL) filed soon after the voluntary disclosure scheme of 1997, the supreme court had asked the government to refrain from introducing amnesty schemes, as it discourages honest taxpayers and let go defaulters, charging a part of black money.

The officials said such schemes encourage “at least the fence-sitters, who are in the dilemma over paying the tax”. “We are trying to push as many people as possible in the mainline economy,” a finance ministry official said. According to finance minister Arun Jaitley, this is the last chance for the tax evaders. “People who have undeclared income and have stayed outside the income tax net, this is the last chance to declare them and sleep peacefully,” he told media after meeting industry and tax professionals on June 28.

Underground economy

Notwithstanding the response so far, experts and officials are in agreement about the need to find innovative ways to unearth the unaccounted money.

A study done by Ambit Capital Research pegs the size of black economy in India at Rs 30 lakh crore or 20 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. Arun Kumar, former economics professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) who has authored The Black Economy in India (Penguin, 1999), believes each of us would have been seven times richer if all the black money were to come out.

The officials, meanwhile, refused to give a precise estimate about the size of black economy in the country. “We do not even know if it has grown or reduced over the years,” one of them quipped.

This huge black hole in the economy is harming the nation in two ways. The government is not getting taxes which are due and those who are generating black money remain immune from regulations. So both from the point of view of governance and of revenue generation, we are suffering because that part of the economy is not reflecting anywhere, said an official, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

A history of failures

Various tax amnesty or income disclosure schemes in the past have not been a huge success. For experts, these schemes symbolise the failure of the government to bring the black economy under regulation. The schemes unveiled in 1985 and 1997 are considered somewhat of an exception. The 1985 scheme yielded a disclosure of Rs 10,778 crore, and the latter brought Rs 33,000 crore worth of black money under the taxation regime. Last year the government had introduced the Black Money (Undisclosed Foreign Income and Assets) and Imposition of Tax Act, 2015, where it charged a hefty 60 percent tax on unaccounted income earned abroad. However, only 644 declarations were received and Rs 2,428 crore was collected in taxes, since there was hardly any pressure – or incentive or threat of action.

So why has the government not been able to tackle the parallel economy even after close to seven decades of independence? At the core of the government’s failure in dealing with black economy are a few structural and regulatory challenges, which continue to dog the economy.

First is the quality of governance: the functionality of public delivery systems. In the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Sweden and Norway, residents pay more than 60 percent of their income in taxes to the government. Healthy tax compliance there is thanks to the fact that citizens also depend heavily on their government for the basic necessities like health and education. “Access to reliable and quality public services creates a natural obligation for people to pay taxes,” said a former CBDT commissioner. Thus, even after paying high taxes, Scandinavians are the happiest people in the world, the official said. In India many do not feel the obligation of paying taxes since public service delivery systems are dysfunctional and people are forced to rely on market for most of their basic needs. “Tax collection is not a police activity. It is a function of governance,” the official said, and there is a limit to how many people you can catch through raids and searches.

Compliance is also related to psychology. People are indifferent to paying higher indirect taxes, which in some cases go as high as 40 percent. However, when it comes to direct taxes, since it is taken directly from their pocket in one stroke, it is perceived differently. The government should work to change this mindset.

Rampant corruption is also an issue. It is the very source of income, which is hidden from the taxation system, and is kept in the form of movable and immovable assets. The money earned through corrupt deals is generally parked in real estate, bullion, or released in circulation at the time of elections. According to a Transparency International report, India is ranked 76th out of 168 countries in the global corruption index.

“If you sell or purchase a house or if you are in construction business, you would pay bribes for getting land sanctions, approvals, at various levels,” a senior finance ministry official acceded. That amount has to be factored somewhere in the business.

For fighting elections parties need cash. “A businessman is certainly not going to pay to the parties from his taxable income,” said the finance ministry official. Money, however, floated during elections is still better than money parked in bullion or real estate. In elections it gets in circulation, which is in a sense good for the economy.

The third factor is administration and governance. The income tax department itself is criticised for rampant corruption. However, over the last decade, the use of information technology has reduced discretion and the number of people filing taxes and returns has increased significantly. Between 2000 and 2011, the income tax collection also increased manifold. It was Rs 31,764 crore in 2000-01 and 11 years later it stood at Rs 1,70,788 crore. “Much of it reflects on the use of computers in the administration,” said the former CBDT official.

Technology to the rescue

At present various organisations under the finance ministry are creating their own databases and are also working on information sharing between agencies. The greater the number of transactions recorded, the easier it will be for agencies to trace back a transaction. Accordingly, the CBDT official said, the agencies will be able to sketch out a profile of the taxpayer.

The income tax department has been building a database for the past five years. The records have been linked with PANs. “Now we have a data warehousing project, in which we are trying to get data from other departments where we can do a search, create linkages, do profiling of taxpayers,” the finance ministry official said. “CBDT is signing MoUs with other departments for sharing of information. The information sharing agreements are already in place between CBDT, custom and central excise,” the official added.

A major landmark would be the Goods and Services Tax Network, the agency in charge of the IT backbone for implementation of GST, which is integrating several departments and databases. It would make information exchange easier, the official said.

The PAN would then be the common identifier, as has been agreed upon by eight departments, through an inter-ministerial group. The PAN will become the basis of all business identification. “It will automatically get linked up with our database. The minute you have one identifier for all transactions, obviously all those transactions will get linked. But making this database is not going to take two or three months, it is going to take years,” the official said.

How about Aadhaar? Aadhaar is an individual identifier. Aadhaar can play an important role when someone is spending but not filing returns. “You can track households, vis-à-vis their source of income,” the finance ministry official said.

Meanwhile, the supreme court-appointed special investigation team on black money in its interim report has also made a bunch of recommendations, officials said. For example, cash transactions above Rs 3 lakh and storing cash over Rs 16 lakh should be banned. Setting a cut-off limit for cash, the official said, will not only impact sectors which are covered under the income tax law but also those which are not – agriculture, for example. “Agricultural produce are purchased and sold in cash. Here you can’t make it mandatory unless you have banking outreach in the rural areas. A restriction is still at a discussion stage,” the finance ministry official said. A decision is unlikely before the next budget, and it would come only after consulting the enforcement directorate, customs and commerce ministry, among others.

Some argue for a radical overhaul of the Income Tax Act, 1961. The voluminous legislation provides for several exemptions and deductions – virtually indicating escape routes. “Wherever you are giving any kind of exemption, its calculation becomes so complex that at every stage there are ways and means to circumvent the law,” the CBDT official said. A more efficient way of dealing with it is to do away with all exemptions. Have a cut-off limit, argue experts. The law should clearly say that everyone earning Rs 100 should pay Rs 5 as tax. Don’t leave space for discretion, the official said. For many other experts, it is impractical and utopian.

The societal perception too needs to be changed. A citizen honestly paying the last penny of the taxes is considered a fool and tax evasion is called smart tax planning. “Until that changes, we can’t change the situation,” the finance ministry official said.

pratap@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the September 16-30, 2016 issue)