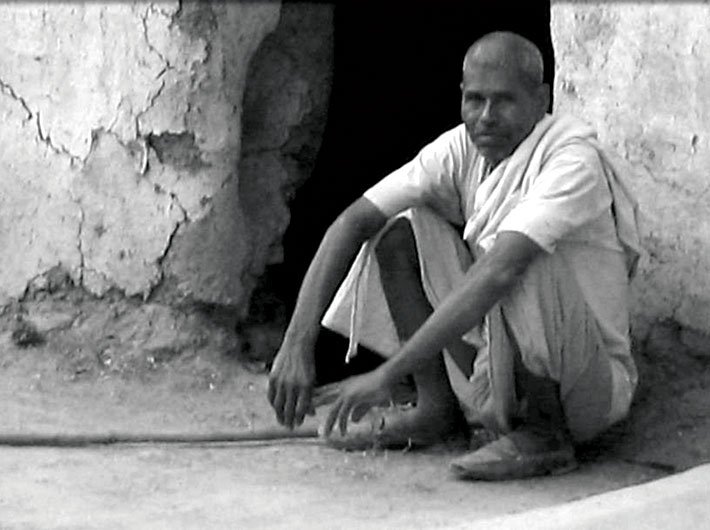

A survey in drought-hit Bundelkhand paints a startling picture of farmers in distress

Bundelkhand, the land of famous warriors Alha and Udal, is entrapped in an unending battle. But unlike 1857, today there is no ‘harbola’ to tell the stories of sacrifices. Then, Subhadra Kumari Chauhan wrote, “Bundele harbolon ke munh hamne suni kahani thi, khoob ladi mardani voh to Jhansi wali rani thi (from the mouths of storytellers of Bundelkhand did we hear a story, the one who fought well like a man was the queen of Jhansi).” There is almost a silence in the times of ‘Make in India’ on this battle against hunger as farmers here are committing suicide in large numbers.

Bundela farmers had once fought as soldiers but today, they are forced to eat ‘ghas ki roti’ (bread made of grass) to sustain themselves. It is not an exaggeration but a finding of a survey conducted by an independent organization,

Swaraj Abhiyan, under the leadership of social activist Yogendra Yadav. He warns that the situation of Bundelkhand is worse than that in Marathwada region of Maharashtra, and is heading towards a famine. Yadav had organised a Samvedna Yatra during October-November in drought-prone areas of the country to study the ground reality.

Nearly 360 farmers have committed suicide in Bundelkhand this year. Swaraj Abhiyan covered Banda, Chitrakoot, Lalitpur, Jhansi, Jalaun, Mahoba, Hamirpur (Bundelkhand region’s seven districts in Uttar Pradesh) and surveyed 1,206 households in 108 villages in 27 tehsils, between October 27 and November 9. According to findings of the survey, this is the third successive drought in Bundelkhand with 96 percent households reporting loss of previous rabi, 92 percent households reporting complete loss of their moong dal and 84 percent households saying they had lost all their arhar dal in the region, also known as the ‘pulse-bowl’.

In the survey, carried out in association with NGO Parmarth, 38 percent villages reported at least one death due to hunger/malnutrition. “Multi-pronged distress” was visible in the area, with 71 percent households reporting indebtedness, 40 percent resorting to distress sale of cattle, 27 percent had to let go off their cattle due to lack of fodder, 27 percent had to sell/mortgage their land and 97 percent said their debts had increased. MGNREGS that guarantees at least 100 days of wage employment under the law has totally failed here. But the most astonishing fact is that up to 17 percent families are eating ‘fikara’, roti made of grass, to feed themselves.

This story of Bundelkhand is a part of the agrarian crisis that India has been facing for almost two decades. More than 2.8 lakh farmers have committed suicide during this period due to crop failure and debt trap. By the end of 2015, nine states of India had officially declared a drought and 302 of the 640 districts are living in drought-like condition.

Drought is not new for Bundelkhand but the frequency is increasing. Government records show that Bundelkhand used to have one drought in 16 years during the 18th and 19th centuries. From 1968 to 1992, the region saw a drought every five years. But in the 21st century, the region has already suffered more than seven years of drought. Even with a minor deficiency in rainfall, the region suffers severely. The canal system is highly underdeveloped with no systematic plans for the preservation of rainwater such as rainwater harvesting. The region had a system of manmade water tanks to face the challenge but the safety net of community-managed tanks is only history now.

Way back in 1989, the erstwhile planning commission had warned about the linkage between deforestation and depleting groundwater. “Bundelkhand, devoid of forest cover, looks like a barren land with naked mounds of hills. The problem of soil erosion, soil filling into the ponds making them useless, direct flow of rainwater into the rivers, depleting ground water resources and unproductivity of the land, all these are the emerging issues in Bundelkhand which have roots into the depletion of forest cover,” said its report ‘Study on Bundelkhand’.

Rapid commercialisation of agriculture and poor irrigation system has greatly increased the input cost of agricultural production. The output, however, has not increased in the same proportion making agriculture a loss-making activity. Getting influenced from the commercialisation of agriculture across the country, farmers of Bundelkhand have also started switching over to commercial crops that require more water. But with the declining availability of water, farmers are forced to look for alternative resources such as ground water. In order to explore ground water, by way of digging wells and installing tube wells, they have to take loans from private moneylenders. This has increased the overall cost of agricultural production.

Jitendra Uttam, an assistant professor at School of International Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University, says that the agrarian crisis in India is a big threat. The focus of policy makers is only on industry, while agriculture has become a neglected field. The agricultural policies we have are not much effective on ground. For cash crops, farmers are using factory-made products that have increased the cost price a lot. Dependency on machines has badly affected the community network and when crop fails, one is unable to find a support system. Finally, farmers fall in the debt trap. “Some years ago, there was no concept of ‘monthly bills’ to be paid by farmers. Now they have to pay regularly for things like cable and mobile connections. So the need for cash is also increasing and when they are unable to manage these, the sense of being poor increases manifold,” says Uttam.

Renowned journalist P Sainath is known for his extensive ground reports of the agrarian crisis. He is a strong critic of the model of development, which showcases multi-storey buildings with swimming pools on every floor in Mumbai and Pune when farmers face acute water shortage for irrigation. According to Sainath, there is a drop of 15 million in the farmers’ population in India since 1991. “On an average we are losing 2,000 farmers every day. Today the farmers (who work more than six months continuously) comprise only 8 percent of the Indian population. The 2011 census clearly shows that the addition in urban population in the last decade is more than the addition in rural population, for the first time after 1921. This is only because of huge migration from rural to urban India,” he said in a public lecture recently.

The situation of Bundelkhand is a loud alarm for the government and civil society as well. We need to think of rural India and its farmers seriously; else not even sufficient grass would be left to make rotis for every Indian.

feedback@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the December 16-31, 2015 issue)