Champaran, the site of the Mahatma’s first major campaign in India after his arrival from South Africa, is ripe for another satyagraha – like the rest of the country

It is a nondescript, small-town railway station. The two platforms have the usual throng: passengers, station staff, vendors, luggage-bearers. Also, people and dogs loitering without intent. Like every dog, many railway stations also have their day. For this one, called Bapudham, it was a hundred years ago.

In April 1917, Mohandas Gandhi stepped down from a third-class compartment at this stop, the railway station of Motihari in East Champaran of Bihar. From here he began his campaign to study the plight of indigo farmers – his first major political action after returning home from Africa.

I try to see and feel what Gandhi must have seen and felt around the same time of the day (afternoon) and about the same time of the year (April 15).

The weather must not have been very different back then. I am pleasantly surprised by a mildly cool breeze instead of the predictable early-summer heat. But then, Champaran – originally Champa Aranya, or Forest of Magnolia, is not far from the foothills of the Himalayas.

Read: A small beginning apparently, but a crucial one, says Irfan Habib

Gandhi’s visit had generated as much hope as curiosity among the farmers, sometimes called raiyyat, here, and a crowd must have gathered to greet him. From the foot-overbridge, I look down at the two platforms and try to visualise, in sepia tones, a crowd of over a thousand people waiting for the arrival of their ‘Mahatma’. Dr Rajendra Prasad, the first president of India and in whose house Gandhi stayed for a while in Patna, writes in his memoirs, “In that journey from Muzaffarpur to Motihari, people had gathered at each station to welcome Gandhi.”

(Platform number two of Motihari railway station from where Gandhi began his journey to Champaran)

Today, the station is teeming with passengers, visitors, security men, vendors, luggage-bearers and onlookers, not to mention dogs. Some have no business with any of the arriving or departing trains; they have come simply to sit under one of the lazily stirring fans or catch the latest gossip of the town. Or fetch water from the newly installed ‘water ATM’, which has replaced the traditional pyaus, just as iron benches have taken place of those made of cement. Towards the right of the main entrance, a glossy LED screen flashes updates on the arrival and departure of 26 pairs of trains. A group of young boys is busy with their smartphones, earphones plugged in.

It is Ram Navami and a Ramayan mandali has gathered in the ‘circulating area’ of the station, outside the station entrance. People are listening to the Ramcharitmanas recital. Gandhi might have sat down, if the recital of his favourite scripture were on when he arrived here. The main hall of the station is not as clean as it should have been. Gandhi might have asked for a broom and gotten down to cleaning it up. The walls are filthy with posters of job vacancies and advertisements promising sureshot cures for various ailments.

Yes, the station remembers its role in the history of India, and I notice paintings, charts and posters of Gandhi and his satyagraha stacked in a corner near the station master’s office. “The station walls are about to get a whitewash. Preparations are on for the centenary celebrations,” a fellow passenger, Manish Ranjan, who is quite familiar with the place, tells me.

“Bapu’s train arrived on platform number two. He reached here at three in the afternoon,” says one of the railway officials in the station master’s office. He suggests that I visit platform number 2 to see Gandhiji’s ‘rare’ statue in which he is ‘in action.’

The 10-foot-tall brown statue displays excerpts from ‘India of My Dreams’ on its base – next to the announcement that this statue was installed by railway minister Lalu Prasad in 2006. The Bihar government has plans to give the railway station a facelift.

****

Indigo and satyagraha

The history of indigo farming in India is quite old. However, during the colonial rule, the British forced it upon the farmers against their wishes. The indigo was not a profit-making crop. More than half of the land in Champaran was owned by the Bettiah estate, which was under heavy financial debt because of poor management. Taking advantage of it, the British took the land on lease to grow indigo.

The farmers, called raiyyats or tenants, were forced to obey their landlords, the British indigo planters. They had to cultivate indigo instead of food crops on whatever little land they had. The colonial administrators in the region imposed a system called ‘tinkathia’, according to which raiyyats had to cultivate indigo on three out of every 20 kathas (unit of measurement) of land they had. It was a stringent system and farmers of this region had to suffer humiliation, poverty and hardships. The indigo farmers were supposed to pay taxes under 20 heads in a system called ‘abvaav’.

“These rules were one-sided and this led to farmers’ exploitation by rich landlords and the British empire. Because of the pressure of growing indigo and growing almost nothing else, the region had suffered five famines between 1870 and 1907,” says Bhairab Lal Das, a writer-researcher from Patna who has been working on Champaran’s history. During World War I, Germany developed a method of producing synthetic indigo, leading to increased pressure on Indian farmers.

(Hardiya Kothi, one of the indigo factories, also called Nilha Kothis, in Raxaul village, Bettiah, West Champaran)

Gandhi arrived in Champaran and won people’s faith in the initial few days when he refused to leave the region against the notice of the district magistrate. For his protests and campaigns, he applied a nonviolent way of disobedience – which he had first tried out successfully in South Africa and called ‘satyagraha’. This led the magistrate of the Motihari court to allow him to stay on. During his stay, he visited several villages, indigo factories, farmers and even indigo planters. He listened to more than 8,000 farmers and recorded their statements. The government was forced to form a committee for the indigo farmers’ grievance redressal. The result was that a Champaran Agrarian Bill was passed in April 1918, ending the tinkathia and abvaav and thus all colonial exploitation of the farmers. This was the first milestone among the several campaigns that Gandhi led during the freedom struggle.

****

Man who brought Gandhi to Champaran

“Kissa sunte ho roj auro ke,

Aaj meri bhi dastan suno”

These were the words of an indigo farmer, Rajkumar Shukla, in one of his many letters to Gandhi. Gandhi was then touring by railway the length and the breadth of the country, looking at his homeland with new eyes. His political mentor, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, had advised him to explore India and its million mutinies before plunging into the freedom struggle.

Shukla met Gandhi in Lucknow during the annual session of the Congress in 1916 and urged him to lend his voice to the indigo farmers. Shukla followed Gandhi to Cawnpore (now Kanpur).

“Champaran is very near here. Please give a day, he insisted,” Gandhiwrites in his autobiography. “Pray excuse me this time. But I promise that I will come,” Gandhi replied. Shukla later followed Gandhi to Ahmedabad ashram and Calcutta (now Kolkata).

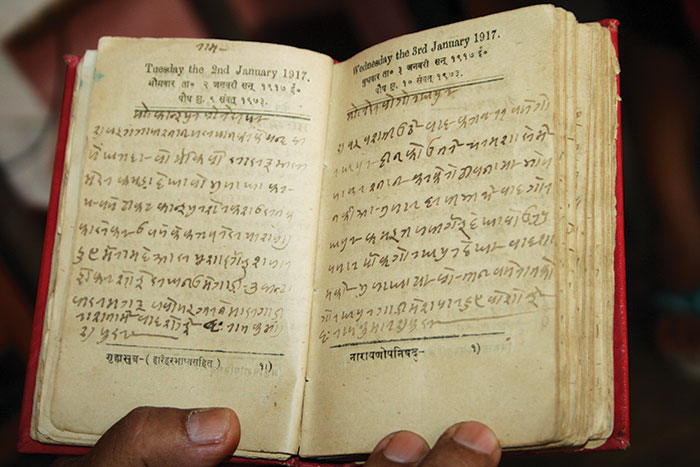

This Bhojpuri-speaking Shukla maintained a personal diary during 1917-18 which is now in possession of his grandson. As he used to write in the old Kaithi script, his diary – a prime document offering a first-person account of the agony and hardships faced by the indigo farmers as well as of the struggle – has been largely ignored by historians and researchers. A Patna-based historian and writer, Bhairab Lal Das, was intrigued when he came across it, and has transcribed it in Hindi as Gandhiji ke Champaran Andolan ke Sutredhar Rajkumar Shuka ki Diary.

(Rajkumar Shukla’s personal diary, in which he maintained everyday’s record of meetings with Gandhi, indigo planters and others)

“Kaithi is a forgotten script of the Hindi belt. It took me one and a half years to translate the script. His writing was crisp, to the point, and had daily accounts,” says Das, who is employed as a project officer with the Bihar legislative council. He started translating the diary in 2011, and completed the work in one and a half years. “No publisher was ready to publish the edited diary and it was only in 2014 that Maharajadhiraj Kameshwar Singh Kalyani Foundation came forward to help publish it,” says Das.

“The book answers several questions about the Champaran satyagraha and has anecdotes which are not available in any other book or government documents,” he says.

Shukla’s village Satwariya, now in West Champaran, is well connected with the rest of Bihar’s towns and villages. However, I see no pucca roads within the village. Entering the village, there is an ‘inter college’ built in the memory of Shukla, who is remembered as ‘Krantikari Shuklaji’. The college is a single-storey building with seven or eight rooms. One has to walk through a dusty ground, which is not exactly a playground, to reach the classrooms. A bust, which locals say bears little resemblance to Shukla, has been installed in the college premises. “My grandfather died young, he was never as old as he appears in the bust. We have the photographs; one can see and match,” says 73-year-old Mani Bhushan Rai, Shukla’s grandson who is living with his family in the village.

(Mani Bhushan Rai, grandson of Rajkumar Shukla, at his home in Satwariya village, West Champaran)

I am sitting in their ‘bahar ka kamra’, the drawing room, and take a look at the framed photograph of Shukla, hanging on a wall. “That’s the only photograph of Shuklaji,” Rai says. To the left of Shukla’s portrait hang pictures of Mahatma Gandhi and Indira Gandhi along with a framed text of the universal declaration of human rights.

Rai, who calls himself a true Gandhian, was out of job after the sugar factory he was working in was shut down in 1992. He is wearing a white vest and a blue lungi and yet sends in a child, who is hanging around, for his khadi kurta. “Politics these days is very dirty. You cannot walk into it if you carry ideologies,” Rai bemoans as he gets into the withered kurta which is torn at many places. “Perhaps that is why I am not even in the management committee of the college built on our land,” he says flipping through the pages of Shukla’s red diary, which is much treasured by the family.

****

Decay and dilapidation

My quest to trace Gandhi’s footsteps in Champaran takes me to the villages that he had visited, the places he had stayed in and the schools and vocational training centres that he had opened for children and women. Gandhi stayed in Champaran for about ten months, till January 23, 1918, busy not only preparing the legal case for indigo farmers but also crafting a template for a ‘constructive programme’. Obviously, there are numerous places of historical significance here, but they are all in a sorry state.

Vrindavan ashram, located about six km from Bettiah, has fallen off the satyagraha map; a room and a statue to commemorate Gandhi’s footprints remain here. The ashram has been left to crumble with only one building remaining. Fifteen years ago, the place was humming with charkhas and women making pickles and other cottage products.

(Vrindavan Ashram caretaker Banhu Bhagat, who grows fruits on a patch in the compound)

The ashram once had 109 bighas of land. A major portion of it was given out to build a Navodaya Vidyalaya, a Rashtriya Buniyadi Vidyalaya, a hostel, a Khadi Gramodyog Centre, a post office, and a health centre. “The ashram had over 20 educational and vocational training centres. Gandhi and Kasturba, along with other men and women, used to spin charkha in their rooms. Very little is left now,” says Sohan Gaddi, the caretaker of the Khadi Gramodyog Centre which operates from the only room that stands with a roof. The charkha and other instruments are dumped in one corner and left to decay.

The Hazarimal Dharamshala in Bettiah is now a garbage dump. Braj Kishore Singh, secretary of Motihari Gandhi Sangrahalaya, blames it on the central and state governments’ neglect over the years. “Most of the sites in West Champaran are decaying because of court and land disputes. The case of Hazarimal Dharamshala is one example. East Champaran is slightly better in condition,” he says.

The Bhitiharwa ashram, in northwest Champaran, is in a slightly better condition; however, it fails to reflect Champaran’s history. Uttam Singh, its caretaker, guides me inside the ashram. All he has to report is that “Gandhi carried out a lot of social work from there during 1917.” This was one of the centres for social work selected by Gandhi when he was in Champaran. “A few years ago, nothing was left of this ashram. It was only after 2011 that the ashram was renovated with the help from the Sabarmati Ashram, Ahmedabad. The room in which Gandhi used to stay was renovated. They provided some photographs, which are, however, not relevant to history of Champaran. A school bell and Gandhi’s desk are the only well-presrved items,” says Aniruddha Prasad Chaurasia, secretary, Bhitiharwa Gandhi Ashram Sarvangik Vikas Samiti. He is unhappy with the functioning of the nearby Kasturba Balika Vidyalaya, established by Gandhi in 1917.

(Gandhi’s three monkeys at Bhitiharwa Ashram in Bettiah)

Today, a khadi centre operates from the ashram, which is run by the Bihar Khadi Samiti. Two statues of Gandhi and a figure of three wise monkeys seem to greet visitors who usually number less than them. The Bihar government has chosen the Bhitiharwa ashram for inclusion in the proposed ‘Gandhi circuit’.

****

How Champaran failed Gandhi

Gandhi’s name lives on in Champaran: apart from the Bapudham station, there are numerous Gandhi chowks, many stretches of town roads, schools, statues, busts and banners. There is even a Hotel Gandhi Inn (in Motihari, not far from the Bapudham junction). There are ashrams and museums named after him. There are girls’ schools, colleges and hostels named after Kasturba. Even a casual visitor can’t miss his presence everywhere – except in matters he would have wished to be remembered for. Fearlessness; fighting exploitation, inequality and untouchability; healthcare, sanitation; basic education.

While championing the cause of indigo farmers, Gandhi realised that the root cause of the problem was fear. Also, ignorance and illiteracy. “The villages were insanitary, the lanes full of filth, the wells full of mud and stink and the courtyards unbearably untidy. The elders badly needed education in cleanliness. They were suffering from various skin diseases. So it was decided to do as much sanitary work as possible and to penetrate every department of their lives,” Gandhi writes in his autobiography. So, he opened schools for girls and women. Voluntary teachers and helpers were called from different parts of the country to contribute to Champaran. The seed of everything that Gandhi worked for later in his life was sown in Champaran.

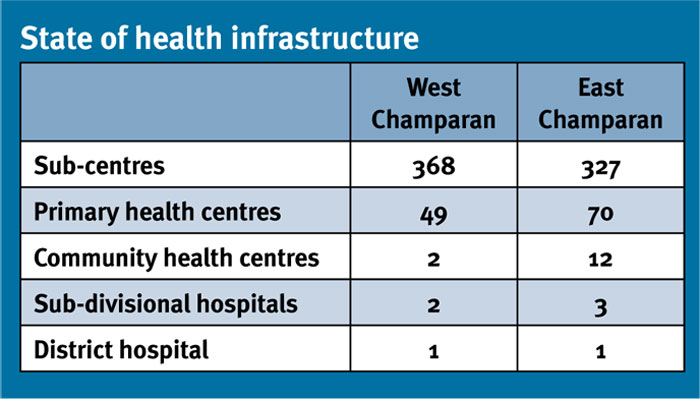

Yet, even 100 years later, almost 50 percent of the population is still not literate. According to Census 2011, average literacy rate in East Champaran is 55.79 percent: shocking but an improvement over 37.54 percent in 2001. While male literacy rate in the district is 65.34 percent, female literacy rate is only 45.12 percent. In West Champaran, female literacy is only 44.69 percent and male literacy is 65.59 percent. Overall literacy is only 55.70 percent.

Wakeel Ahmed Barmaky, whose family has been living in Champaran since 1905, says, “It isn’t that there are not enough schools. In fact, some of the educational centres here are quite renowned and people from other parts of Bihar come here for studies. But taking the local children to the schools is a problem; they either work as labourers or help parents in their work.”

The region isn’t doing well on the sanitation front either. According to the Swachh Bharat Mission data, household toilet coverage in East Champaran is only 27.88 percent and in West Champaran it is only 27.31 percent.

In West Champaran, 63.9 percent girls marry before the legal age, 80.8 percent households have ‘low standard of living’, 28.6 percent women go for institutional delivery, only 7.7 percent women and 43 percent men are aware of HIV AIDS, according to the district health action plan 2010-11.

Situation is more or less the same in East Champaran. A household survey in East Champaran has revealed that 42.8 percent of girls in rural areas married before turning 18. The block-level data shows that 47 of the 4,227 girls who got married last year were less than 18 years. There is no specific data on gender-based violence but the household survey states that women take it as part of marriage and hence undermine the fact.

Farmers of the blue soil

I travel some five kilometres north from Bettiah to reach Raxaul village. Here, on the banks of the Chandravak river stand the remnants of over 100-year-old building built in colonial style. The remaining red bricks have turned black. The only other colour visible nearby is the green of the vegetation and weeds growing from within the walls. An old chimney on the top of the left corner hints at the existence of a warehouse inside its premises. The chimney now covers the trunk of a tree that has found it convenient to grown in such a way that its branches now spring from the black column.

The nondescript structure, the tallest standing amid wheat fields, was Hardiya Kothi, one of the main indigo factories in Champaran. It was one of the 13 kothis set up in the region in 1885. In Bhojpuri language, these factories, which often served as the residence of the indigo planters, were called ‘nilha kothi’, or the indigo planter’s bungalow. Relics of these factories can still be found in rural Champaran. These factories used to be surrounded by huge farms where indigo was cultivated.

“Not a chest of indigo reached England without being stained with human blood… I have had raiyyats before me who have been shot down by the planters. I have put on record how others have been first speared and then kidnapped; and such a system of carrying on indigo, I consider a system of bloodshed,” E De-Latour, an officer of the Bengal Civil Service, wrote in his report in 1848.

Such kothis once sent shivers down any farmer’s spine. Today, farmers are not giving a second look to the Hardiya Kothi, busy as they are with the ready crop of wheat and mango. “Chait me gehu ka katai hota hai [wheat is harvested in the month of Chaitra],” Sabri, a woman in her late 40s, tells me. The owner of two bighas of land, she is busy making plans for harvesting and giving instructions to farm labourers.

(The farms near indigo factories. The soil, once blue, now yields golden wheat in abundance, apart from sugarcane, maize and bananas)

The soil used to be blue once. It now yields golden wheat in abundance as well as sugarcane, maze and banana. Almost 90 percent of the population in the two Champarans lives in villages. The region is well irrigated by a network of rivers like Gandaki, Kosi and Chandravak.

Sabri’s forefathers were indigo farmers. “My grandfather faced atrocities from indigo planters. We had nothing to survive on and he sent my father to Jaunpur in Uttar Pradesh. I grew up there but decided to come back to Champaran with my husband who also has his roots in the region,” she says.

I ask whether anything has changed. She says, “How can I say? I was not born in those years. But I am not dying without food certainly.”

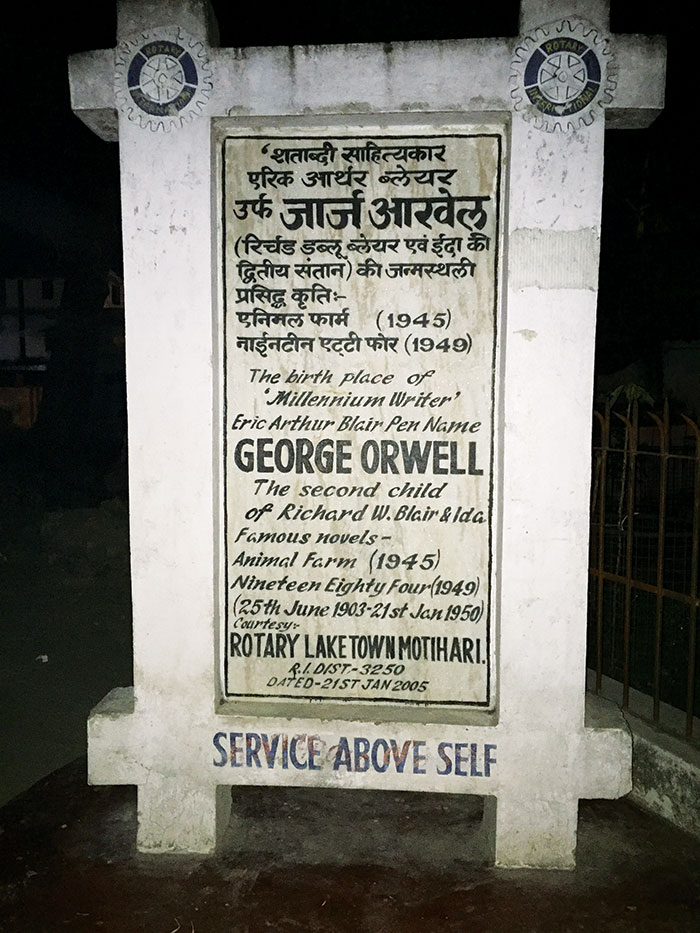

Orwell’s words and the old house

Though it has given up on living up to one legacy, Motihari actually has one more as well. George Orwell (pen name of Eric Arthur Blair) was born here. Only in recent years did the administration wake up, renovated the dilapidated bungalow where his father, a clerk in the opium department of the British raj, placed a bust and a plaque, and officially bestowed the place the historical status. The bungalow is right next to the Shatabdi park, a popular landmark in the town. But little is known of this heritage.

(Birthplace of writer George Orwell in Motihari)

The administration is represented here by Lallan Baitta, the caretaker who keeps the place clean and spends his time gossiping with women unless there are visitors to accompany around the bungalow.

“People come searching for this house. I am not aware who he [Orwell] was. They say he was a vihcharak [thinker],” says Baitta.

Orwell and Gandhi never met each other. But they share at least this much of a common ground. And a mutual acquaintance – Balraj Sahni. The Bollywood actor was once an inmate of the Sevagram Ashram, Vardha. He was handpicked – with Gandhi’s permission – by the All India Radio chief Lionel Fielden in 1939 to assist Orwell in preparing what were essentially propaganda broadcasts during the World War II for the Indian audiences. One can only suppose that Orwell’s critical yet admiring views on Gandhi must have been coloured by reminiscences Sahni might have shared.

This is Orwell’s summing up of Gandhi:

“One may feel, as I do, a sort of aesthetic distaste for Gandhi, one may reject the claims of sainthood made on his behalf (he never made any such claim himself, by the way), one may also reject sainthood as an ideal and therefore feel that Gandhi’s basic aims were anti-human and reactionary: but regarded simply as a politician, and compared with the other leading political figures of our time, how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind!”

swati@governancenow.com

(The article appears in May 1-15, 2017 edition of Governance Now)