Muzaffarpur outbreak illustrative of unexplained and frequently under-investigated public health threats, says the report

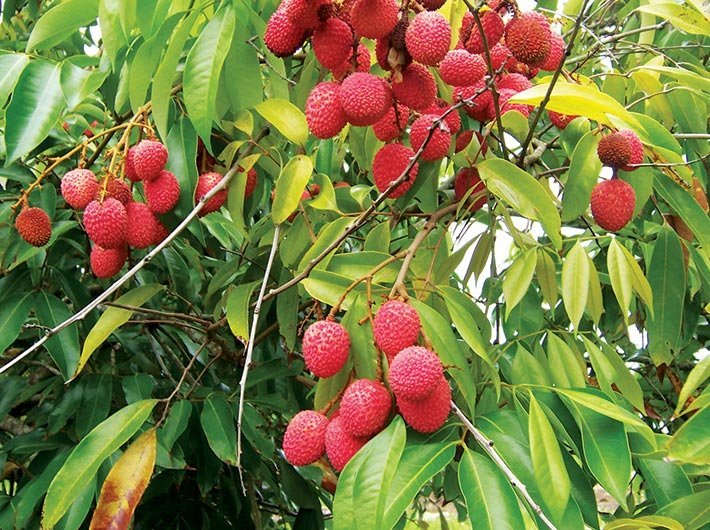

Scientists and researchers have found that consumption of litchi fruit has been increasing child mortality in India. Since 1995, Muzaffarpur district of Bihar, the largest litchi fruit cultivation region in the country, has been reporting seasonal outbreaks of an acute unexplained neurological illness. The illness characterised by acute seizures and changed mental status – often in early mornings – has led to high mortality. These recurring outbreaks begin in mid-May and peak in June, coinciding with the month-long litchi harvesting season. Children from poor socio-economic backgrounds in rural Muzaffarpur are the worst causalities.

An investigation was initiated by the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), India, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC) in 2013 with the focus on characterising the clinical and epidemiological features of illness and assessing potential infectious causes.

READ: Battling to save kids’ lives – and ethics of research

Surveillance was done at the Shri Krishna Medical College Hospital (SKMCH) and the Krishnadevi Deviprasad Kejriwal Maternity Hospital (KDKMH) – the chief referral medical centres in Muzaffarpur. Between May 26 and July 17, 2014, 390 patients meeting the case definition were admitted at both the hospitals, out of which 122 (31%) died. On admission, 204 (62%) of 327 had blood glucose concentration of 70 mg/dL or less.

More than six samples of litchi fruit of unripe, ripe plucked from tree, and ripe fallen on the ground categories were collected from orchards in the five blocks of Muzaffarpur between May 19 and June 13, 2014, and were tested under different temperature settings. In 36 litchi arils tested from Muzaffarpur, hypoglycin A concentrations ranged from 12.4 μg/g to 152 μg/g and (methylenecyclopropylglycine) MCPG ranged from 44.9 μg/g to 220 μg/g. The quantitative evaluation of a small number of litchi arils (edible fruit) collected in Muzaffarpur indicated approximately twice the level of detected hypoglycin A as well as MCPG in unripe versus ripe fruits.

The laboratory investigation found no evidence of a known infectious cause and clinical data indicated that the illness was consistent with a non-inflammatory encephalopathy. A common laboratory finding was low blood glucose (<70 mg/dL) on admission which was also associated with increased mortality.

“Absence of clinical, epidemiological or laboratory findings to support infectious pathogen, pesticide and heavy metal related causes of illness suggest the observed protective association of routinely washing fruit or vegetables was not directly related to a toxin or infectious agent. These findings focused our attention on the possibility that children in Muzaffarpur were exposed to an environmental toxin which resulted in low blood glucose and, subsequently, seizures and encephalopathy,” say the findings published in The Lancet Global Health.

During May and June young children in affected villages frequently spend their day eating litchis in the surrounding orchards. Many return home in the evening uninterested in eating a meal. Skipping an evening meal is likely to result in night-time hypoglycaemia particularly in young children who have limited hepatic glycogen reserves which would normally trigger β-oxidation of fatty acids for energy production and gluconeogenesis. However in the setting of hypoglycin A/MCPG toxicity, fatty acid metabolism is disrupted and glucose synthesis is severely impaired which can lead to the characteristic acute hypoglycaemia and encephalopathy of the outbreak illness.

The study recommends minimising litchi consumption among young children, ensuring children in the area receive an evening meal throughout the outbreak season and implementing rapid glucose correction for children with suspected illness.

Observing that limitations in the ability to provide aggressive critical care including closer respiratory monitoring and mechanical ventilation which probably contributed to mortality among affected children despite the administration of dextrose supplementation, it says that “at a broader level the Muzaffarpur outbreak is illustrative of unexplained public health threats in resource constrained settings whether localised or regional that are frequently under-investigated”.

An outbreak of a similar acute neurological illness with hypoglycaemia and seizures was reported in June 2014, among young children in Malda, a litchi cultivation district in West Bengal.