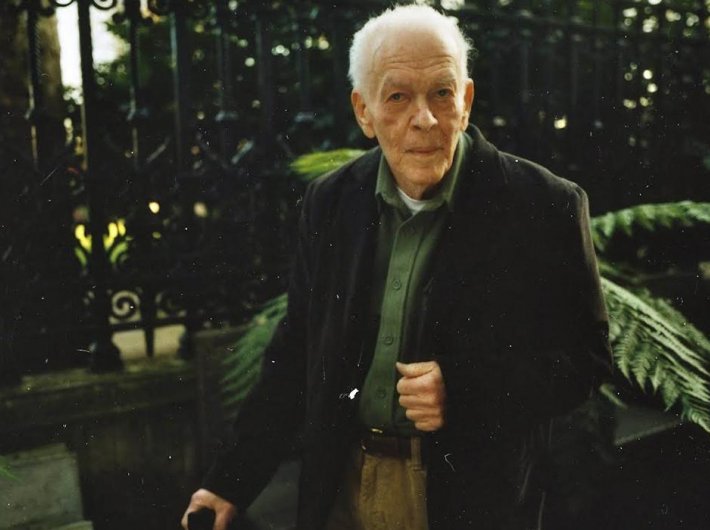

Gene Sharp, the American political scientist, distilled lessons in nonviolence, inspired change around the globe

When it comes to nonviolence, Gene Sharp’s influence is arguably next only to Gandhi’s. Sharp, a political scientist who continued his studies on peace and power from the Albert Einstein Institution he founded, died peacefully at his home in Boston on January 28. Though he had recently celebrated his 90th birthday, he had chosen to continue to work rather than retire.

Scholars and activists have for long turned to his writings for explanation and inspiration on peaceful methods of conflict resolution. In recent times, Ukraine’s Orange Revolution (2004) to the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement against economic inequality in the US (2011) were partially credited to his silently incendiary writings.

Right from his early youth, he must have been influenced by the life and thought of Gandhi – his MA thesis, way back in 1951, was on ‘Nonviolence: A Sociological Study’. That year, he also moved from Ohio to New York and continued his Gandhi studies, preparing his first major work in 1953, when he was barely 25. He must have been pleased when it was eventually published by Gandhi’s own Navajivan Publishing House in 1960. The book, ‘Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power’, presents three case studies of nonviolence in action: Champaran 1917-18, the ‘independence campaign’ of 1930-31, and the independence campaign afterwards.

In his foreword, Albert Einstein wrote:

“At the Nuremberg trials the following principle was put into practice: The moral responsibility of an individual cannot be superseded by the laws of the state. May the day come soon when this principle is not merely put into operation in the case of citizens of a vanquished country! Gene Sharp may have drawn the strength to complete his work from the inner struggle these problems have engendered. No attentive reader will be able to ignore its effect.”

The 1950s turned out to be an eventful decade for Sharp. He was jailed for his civil disobedience against conscription for the Korea war. For this move, he found support from many including Einstein. By then, he was also an associate member of the Gandhi Peace Foundation, Delhi.

In a career spanning more than half a century, Sharp diligently went on to publish score of books, tracts and pamphlets. In particular, ‘198 Methods of Nonviolent Action’, a veritable playlist of tactics compiled from lesser-known aspect of history, is among his most useful works. (The ‘Methods’ is part of a three-volume magnum opus ‘The Politics of Nonviolent Action’.)

Sharp was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize four times, and won the Right Livelihood Award in 2012. “Sharp devoted his life to studying nonviolent struggle, deeply researching and documenting its use in human history, analysing how the technique operates cross-culturally, and sharing the results of his research with other scholars, practitioners, organisers, government institutions, and citizens and civil-society groups on every continent. His numerous books and articles on the subject have been translated into more than 50 languages, and are disseminated worldwide,” says the obituary note of the Albert Einstein Institution. “His work continues to inspire and enable people engaged in struggle to wield social power by building on and learning from the experience, results, bravery, and sacrifice of those who have come before them.”

“Drawing on Henry David Thoreau and Mahatma Gandhi, Sharp’s groundbreaking book, ‘From Dictatorship to Democracy,’ provided the foundations for most nonviolent resistance movements of the last three decades,” Human Rights Foundation (HRF) president Thor Halvorssen said in tribute. “Sharp's work has proven to be invaluable as a source of education and inspiration for the brave individuals tasked with initiating nonviolent revolutions across the world. Sharp’s spirit will live on through the work of every person who labors for a freer world using non-violence as a weapon of resistance.”

Noam Chomsky, a fellow gadfly, in his tribute said, “Gene Sharp made fundamental and original contributions to the theory and practice of non-violence, a contribution of immense significance in an age of brutal violence under the spreading shadow of virtual extermination.”

Chomsky, not exactly a Gandhi fan, is right. Gandhi preached and practised the seemingly impossible nonviolence mode of political resistance during a particularly cruel time of history – with the excesses of colonialism and fascism. Sharp, not a practitioner mostly but a researcher and mentor, was advocating peaceful means in no less violent times, when the state itself was often the biggest source of violence. Yet, over the years, Sharp’s views came to differ from Gandhi’s.

Eminent Gandhi scholar Thomas Weber, for example, writes:

“When he was specifically asked to address the links between Gandhi and nonviolence, Sharp noted that the Mahatma ‘tried to convince people who did not believe in ahimsa [nonviolence] on ethical grounds to adopt nonviolent methods as a practical expedient, a technique that works’. In his foreword to a later edition of ‘War Without Violence’, Krishnalal Shridharani’s 1939 classic study of Gandhi’s satyagraha, Sharp makes it clear that he is much less interested in the extreme religious pacifist and moral arguments approach to nonviolence, which emphasises conversion (that is, arguably, Gandhi’s approach), preferring instead a ‘technique approach’.” [Gandhi Marg, 2006]

Weber prefers to call him “the Clausewitz of Nonviolent Action” – echoing the British journal New Statesman’s description of him as “Machiavelli of Nonviolence”. But the best tribute to Sharp, however, might have come from a Lithuanian defense minister who, going by an anecdote, after reading ‘Civilian-Based Defense’ said:“I would rather have this book than the nuclear bomb.”