There’s much to be said for the grand vision – doubling farmers’ income. But ground reality makes it a promise that is unlikely to materialise soon

Early in March, farmers of Maharashtra belonging to tribal and backward groups marched from Nashik to Mumbai under the aegis of the CPI(M)-backed Akhil Bharatiya Kisan Sabha. They wanted to draw attention to their sorry plight: they have been cultivating forest land which by law should have been transferred to them but hasn’t. This demonstration was different from those organised by powerful farmer groups from across India – in Maharashtra itself, in Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and many other states. When even powerful farmer groups demand job quotas, it is clear that agriculture is in an unprecedented crisis. Those hit worst are marginal farmers with little or no land. In this scenario, prime minister Narendra Modi’s promise to double farmer income by 2022 assumes significance. We look at the farmland crisis with a field report.

According to 40-year-old Ramphal Singh, a farmer is happy only on two occasions: one, when he sees a standing crop; two, when it is ready for harvesting. “After that, he only cries,” says the farmer from Barwala village, Muzaffarnagar.

In the mud-plastered courtyard of his farmstead, some 15 km from Muzaffarnagar town in Uttar Pradesh, Ramphal, his three brothers and two farmer friends are making some calculations as they rest on a charpoy. One of them is jotting down the figures on the back pages of a school notebook. They say it’s an exercise that saddens them, working out farming expenditure and arriving at their meagre earnings.

Like many others in Barwala, Ramphal is a small farmer. The four brothers hold about five hectares on which they grow mostly wheat, rice and sugarcane. At present, they have sown wheat, their only asset and source of food security. The mere thought of property distribution frightens Ramphal. If ever the four brothers decide to share the land, they would get a little over a hectare each. Ramphal and two brothers live on what farming brings them, the youngest is a police constable in Ghaziabad.

“We never calculate our investment and expenditure,” says Ramphal. “If we start doing that, we’ll die of heart attack.” The extended family of 21 members owes Rs 7 lakh, of which Rs 5 lakh was borrowed from a bank and Rs 2 lakh from a moneylender. The bank loan was for a tractor, and the rest for the treatment of a son who died a year and a half back because of kidney infection. “I’ve not been able to repay the debt,” he says. “It brings tears to my eyes when I think about my land being on mortgage.”

Ramphal’s troubles are typical of small and marginal farmers across the country. Nearly 3,000 farmers committed suicide in 2015; 80 percent of them were driven by unpaid loans. The average value of these loans is Rs 2 lakh, a drop compared to the Rs 11,300 crore involved in the Nirav Modi scam. The irony can’t be starker: the jeweller may well go untouched, while these farmers ended up committing suicide.

Ramphal invested a huge amount five years back with the hope of getting good returns. It never happened. While the farming sector slipped into an economic crisis (read interview with Himanshu), the cost of cultivation and other household expenditure increased. The situation was grave across India. Against that we have prime minister Narendra Modi’s vision: doubling farmers’ income by 2022.

Modi first spoke of his vision at a farmers’ rally in February 2016. Later, finance minister Arun Jaitley said in his 2016 budget speech: “We are grateful to our farmers for being the backbone of the country’s food security. We need to think beyond ‘food security’ and give back to our farmers a sense of ‘income security’. The government will, therefore, reorient its interventions in the farm and non-farm sectors to double the income of the farmers by 2022.” The point was reiterated in the 2017 and 2018 budget speeches, and an expert committee headed by Ashok Dalwai was set up. The committee has written 14 volumes on the subject, of which 11 reports are in the public domain.

But for Ramphal and farmers like him, it’s difficult to believe in the prime minister’s vision. “We produce 70 quintals of wheat on our land, of which we sell 50 quintals. The total expenditure is almost Rs 53,000 and when it is sold in the market it gives us Rs 65,000. The overall return is Rs 12,000,” says Ramphal’s eldest brother Mohan Singh.

Input subsidies

Seed is the primary input. Ramphal buys it for Rs 5,500. He and other villagers are aware of subsidies on seeds purchased from co-operative societies. The one nearest to Barwala is 11 km away. On purchase of a kilo of seed costing Rs 25, a subsidy of Rs 9 is given. Ramphal no longer buys seed from the society. “To avail of the subsidy, we have to spend money on transportation. It is better to buy from nearby private shops, three km away,” says Narendra Kumar, a farmer friend of Ramphal. He says the issue is the non-availability of the seed varieties that farmers want; besides, he says, coops often cheat them on weight.

It’s the same story for fertilisers and pesticides. More expensive than seeds, they are used thrice during a crop cycle. Ramphal spends almost Rs 10,000 on fertilisers and pesticides. Even after getting them at subsidised rates from the society, he has to spend from his own pocket. Like other farmers in the village, he is quite unhappy with the direct benefit transfer (DBT) of subsidy in bank accounts, which aims at making farmers pay the full amount while buying material and wait for the subsidy to be deposited into their accounts. Somewhat like cooking gas subsidies.

Mohan Singh says, “Fertilisers and pesticides cost a good deal. It will affect us financially if we have to deposit the money in one go and wait for the subsidies to be transferred...that could take days. We’ll have to borrow during the peak cultivation season, and how many times will we have to visit the bank to check if it is transferred?” Interestingly, the policy is to allow a farmer to purchase fertilisers through point-of-sale (PoS) machines while the subsidy will be transferred to his bank account after his transaction details are uploaded on retailers’ websites.

Currently, the government data shows about 1,30,000 PoS machines are given to fertiliser retailers in 14 states where DBT has already been rolled out. More than 2,00,000 machines will be installed across the country by March this year. Since the scheme is Aadhaar enabled, it is likely to have technical glitches like biometric authentication. A survey by Microsave, a government-mandated organisation, in 200 outlets of 88 districts shows that 88 percent farmers are unaware of the Aadhaar requirement to buy fertilisers.

Besides, the government is also working on measures to reduce consumption of urea – the largely used and heavily subsidised fertiliser. But it has turned out to be less effective. Urea manufacturers were mandated in 2015 to coat urea with neem to minimise its harmful effect on soil and prevent its usage in milk adulteration.

Narendra Kumar says a farmer suffers the most when he gets poor quality seeds, fertilisers, and pesticides. “Poor quality fertilisers and pesticides reduce the overall yield. There should be a facility for testing these chemicals at least once in the lab before they are spread on the field,” says Narendra.

Fertiliser testing facilities are provided under the soil health management (SHM) scheme, but farmers are not aware of it. In 2014, under the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture, the scheme was introduced to improve soil health and encourage farmers to go for the judicious use of fertilisers. Soil health cards are issued on which recommendations to farmers are given to improve soil fertility and quality control of fertilisers. “These cards are made casually without following any guidelines. There are recommendations mentioned on the card. Neither the farmer is aware nor the officials are interested in creating awareness about it,” says Rajiv, who works in the agriculture department in Muzaffarnagar district.

Irrigation problems

Farmers in Barwala and other nearby villages are dependent on the conventional method of irrigation. They take water from the diesel-run tube wells of big farmers and pay rent for it. Ramphal pays at least Rs 400 for three hours. The total cost throughout the cultivation season works out to Rs 9,000. There’s much wastage of water in the process because efficient irrigation methods are not followed. So farmers end up depending even more on the rain.

Out of the 160 million hectares of cultivable land, only 65 million hectares is irrigated. The country has faced successive droughts in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2014 and 2015. The Economic Survey 2017-18 clearly states that the income from agriculture will see a downturn of 25 percent due to climatic changes in the coming years. Agriculture experts are suggesting of micro-irrigation using drip or sprinkler system. The finance minister, in the 2017 union budget, announced a micro-irrigation fund for addressing the ‘per drop more crop’ goal under the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana. A Rs 5,000 crore fund was to be set up by NABARD. The fund was approved by the ministry days before the union budget 2018 was released. Besides, in this year’s budget, a long-term irrigation fund of Rs 40,000 crore has been introduced. The ministry of agriculture and farmers welfare data shows that only 8.6 million hectares is under micro-irrigation. Ramphal and his friends are aware of drip and sprinkler technology but they are apprehensive about it. They fear the equipment won’t work in the plains as it has the chances of getting choked and can be easily stolen or destroyed.

Meanwhile, Ramphal spends Rs 5,000 on diesel for the tractor; more than Rs 9,000 on labour wages during harvesting; Rs 8,000 on threshing and at least Rs 4,000 on other expenditures including transportation to the mandi for sale.

Market linkages

The biggest challenge is after the harvest. With no storage facility nearby, farmers are in a rush to sell their produce at the earliest. They don’t mind selling it to government-run mandis at the MSP or commission agents or private flour mill owners to get a fair price for their produce. A farmer has to face multiple issues once he reaches the mandi with the produce. Like Ramphal many in the village don’t prefer selling their produce to government dealers. “The first thing is to pay money to the commission agent. To sell the produce to a government dealer means waiting for two to three days. The buying is at a very slow pace. Once the jute bag is opened and emptied on the ground for weighing you have to sell it within a day,” says Ramphal. It leaves farmers helpless as they cannot take back the crop and have to sell it at the best price given on that particular day. “Private buyers derive the benefit out of our stranded situation. Therefore, by evening we sell the produce to private players at the reasonable price. Occasionally, we get good money,” says Ramphal.

MSP based procurement

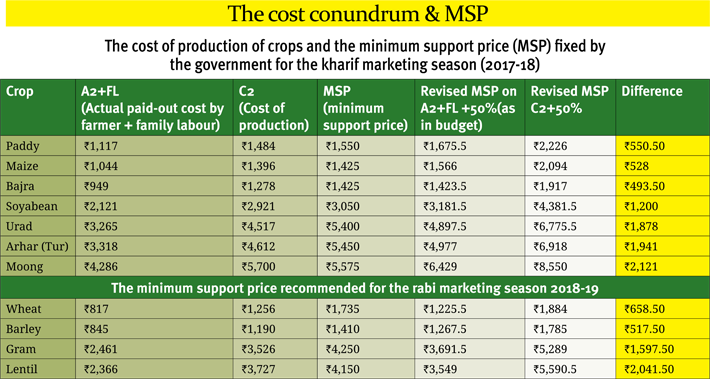

Farmers, generally, get to know about the MSP after sowing. Many farmers are pushed into debt and distress due to poor remunerative prices. It is the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) that projects the cost of the agriculture commodities on the basis of actual paid out cost by the farmer (referred as A2) and imputed value of family labour (referred as FL). By adding the two, the MSP is generated. In 2017, the projected cost of maize, kharif crop was Rs 1,044 per quintal and recommended MSP was Rs 1,425 per quintal. However, it was sold in the market at Rs 1,050-1,100 per quintal in December. Likewise, urad was sold at Rs 3,500 per quintal while its MSP was Rs 5,200 per quintal. The variation in MSP cannot be attributed to demand and supply in the local or domestic market. The import and export policy of food grains and international prices have an important role to play. (Read Himanshu and Ashok Gulati’s interview for detail on pulses policy).

In 2014, the prime minister in his election campaigns promised of 50 percent margin over the cost of production (C2) which includes all the cost incurred in production including rentals to increase the MSP. Social activist Yogendra Yadav says that the prime minister has broken his promise of raising the MSP as per C2+50% calculation. A green paper published by Yadav’s organisation Swaraj Abhiyan shows that the MSP in last four years has been kept substantially low to an extent that out of 20 crops for which MSP is declared, seven crops showed negative returns. Meanwhile, in the remaining crops, the returns were marginal – only two to eight percent.

The centre prohibited the state governments from declaring additional bonus in MSP for farmers in 2014-15. The paper contests that there has been an attempt by the government to bring up (A2+FL) as the basis of cost of production to show higher margins. The CACP reports clarify that net returns are over C2 while A2+FL is the gross return.

Even the finance minister, in this year’s budget, mentioned that the MSP would be one-and-a-half times of the cost of production but he did not mention whether it will be on A2+FL or C2. The mystery still looms over the formula of calculating MSP. Yadav in a press conference held soon after the budget said that in 2015, the government filed an affidavit in the supreme court saying it won’t be possible for them to increase the MSP on C2+50 percent formula.

On the other hand, in order to remove middlemen and commission agents, the government’s thrust is on expanding the electronic National Agriculture Market (e-NAM) – an electronic marketplace to directly link farmers with buyers in different states. Until December 2017, 470 markets across 14 mandis have been integrated with the e-NAM portal.

Surprisingly, farmers in Barwala village are unaware of it. The FM in this year’s budget announced of expanding the coverage from the current 250 markets to 585 APMCs.

Getting insured

“The bank does not inform us about the insurance. Somehow we are made the beneficiary of the scheme at the time we apply for the Kisan Credit Card. We are already in debt and on top of that the premium amount is added. There are so many issues in making a claim that none of us in our village has received any benefit,” says Narendra. Many farmers in other villages complained about it too.

Under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) a farmer has to pay a premium of two percent for food crops and five percent for commercial crops while the remaining amount is paid by the centre and states. A state chooses insurance companies, through bidding, which charge a minimum premium. The purpose is to reduce the premium burden on the government. But data show the average premium collected across the country has increased by 12.55 percent of the insured amount. Meanwhile, reports show that in 2016-17, the gross premium collected by companies was Rs 22,004 crore while the total claims were paid only Rs 12,020 crore.

“On what basis is the government talking about doubling our income? There are so many schemes but we are scared of them now. At the end it will only increase our financial burden,” says Ramphal Singh.

feedback@governancenow.com

(The article appears in April 15, 2018 edition)