Poor, ageing and inadequate water-related infrastructure in our cities is one of the reasons for rising incidence of diseases. A look at the issue, and zooming in on addressing it

The ongoing monsoon may have given respite to urban residents from sweltering heat, but their environment offers a breeding ground for various water- and vector-borne diseases. Diarrhoea, Shigella, dengue and tuberculosis have emerged as urban diseases and public health concerns. Existing pathogens/viruses are increasingly adapting to the new urban environment and several others are re-emerging. The growing economy, high mobility of urban population, dilapidated water infrastructure, social inequality and vote-bank politics have created a conducive environment for diseases. The 2014 revision of the World Urbanisation Prospects by UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs) warns of the largest urban growth in Asia, and hence it is important for India to be prepared to contain the urbanising diseases.

Incidences of urban diseases are reported before, during and after monsoons. Urban authorities assume diseases are a concern of the health department and question the lethargic response of urban medical officials and hospital officials. This is further compounded with the disengaged approach of national and international agencies to address issues of drinking water, sanitation and sewerage systems in urban India. In recent years, various cities and state governments have gone commercial by introducing bottled water and automated water vending machines. It is basic science that about 80% of the water consumed is discharged as waste by humans. What are the existing mechanisms to dispose this wastewater?

A parliamentary panel in 2012 expressed its “distress” over the implementation of one of the largest urban development programmes in the country – the Jawaharlal Nehru national urban renewal mission (JnNURM). It found that over 50% Indian cities did not have sewerage connections and only 21% of them had their wastewater treated. The result is a combination of drinking water pipelines supplying poor quality or priced water and lack of sewerage connections to dispose wastewater. As a result, people are drowning in their own wastewater. Storm-water drainage is almost non-existent in urban India. People are often blamed for their unhygienic lifestyle, but with inadequate water, sanitation and sewerage system, poor housing and insecure land tenure, maintaining hygiene becomes impracticable, especially when the environment is filthy.

Poor water infrastructure is claimed to influence human health. However, there is a dearth of studies that could reveal the link between poor quality of water infrastructure and disease prevalence. Water infrastructure in all our cities is ageing. It was created about 50 years ago as per the needs of the then population and is in a dilapidated condition now. Information on the current status of this infrastructure is all elusive and is exploited by various actors. Vote-bank politics, encroachment of public space, illegal water connections, growing informal settlements and inability of local governments to address the crisis adds to the chaos.

Improving water infrastructure in urban areas is absolutely essential to the growth and health of cities. There are many technical, medical and socially engineered advances to address water supply and sanitation issues in urban areas, but turning the tide against these killer diseases threatens to be unachievable. While everyone is to be blamed for the crisis, there is no magic wand.

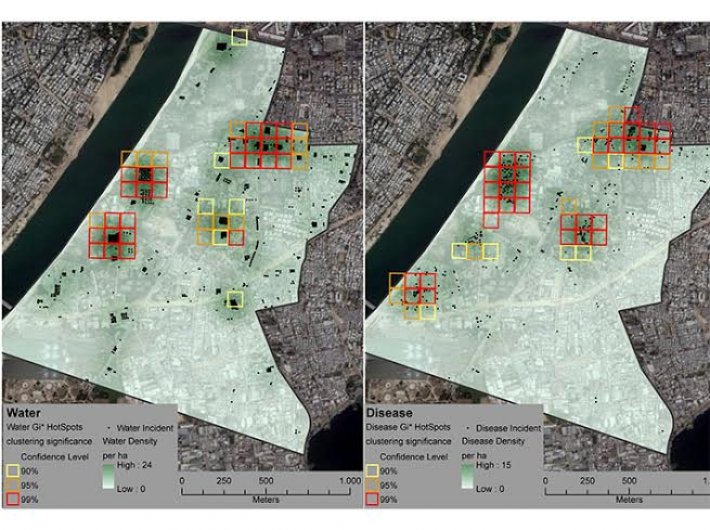

An ongoing collaborative research, being conducted in Ward A and Ward B of Ahmedabad for 2011 and 2012 [the names of the wards are kept anonymous], offers a way forward by integrating and geo-referencing micro-level sector-wide information, especially on the quality of water infrastructure and occurrence of diseases in municipal wards. Supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), it will help us identify the hotspots of disease emergence and the quality of water infrastructure through spatial mapping of water networks (only legal pipelines).

They document and geo-reference water infrastructure problems registered with the authorities. In this book, households register their everyday complaints about road, water, sewerage and other public works issues. The register contains a wealth of information about the complainant (name and address), the nature of the complaint, location of the complaint (address or landmark) and the remarks of the junior engineer on whether the reported case has been addressed. These complaints are based on the people’s day-to-day experiences and observations in their settlements. The report is an important documentation that makes the infrastructure visible through everyday problems. The register runs into several hundred pages, and there are four or five books for each year.

The information is not compiled in any way (for politically convenient reasons) for precautionary decision-making, but is rather used as a ‘fire-fighting’ approach by junior engineers to address day-to-day complaints. The research team documented and geo-referenced the location of complaints on poor water quality, water leakages and low water pressure for analysis.

The other set of information on the health status of urban residents is available with local healthcare authorities. This statistical information is integrated and analysed to locate the hotspots of disease emergence and its link with settlement types in the two selected wards. Ward A is in the oldest part of Ahmedabad city, with many informal settlements comprising poor housing and abandoned textile mills. In contrast, Ward B is a planned settlement developed in 1970s. This however, has not deterred the growth of informal settlements here. Moreover, poor maintenance and inadequate regulation of planned housing has made the ward a breeding ground for water-related infectious diseases.

The findings from this collaborative research would be published in the Journal of Industrial Ecology (http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12172) in August. The findings reveal that the head-reach of the pipeline has higher density of water networks. The data suggests that this area of the ward has bungalows and housing societies and have better access to drinking water. As the pipelines reach the tail-end, the density of the water network decreases and leads to the mushrooming of informal settlements, which presumably have less access to drinking water, but not in terms of illegal water connections.

Complaints on water leakages and poor water quality were found to be high on the tail-end where the housing was poor and environment filthy, compared to the head-reach. The households in the head-reach also had enough resources to gain more access to water (by using electric pumps and additional storage devices within their houses) and treat water, and also had better access to health care. This is in contrast to the people living in informal settlements with poor housing quality, with lesser water supply often poor in quality and higher malnourishment conducive to disease.

The analysis showed strong spatial coincidences between poor quality of water infrastructure (water leakage, poor water quality and low water pressure, clubbed together as ‘water’) and occurrences of diseases (jaundice, gastroenteritis and malaria, clubbed together as diseases) [Fig. 1 and Fig. 2]. Unfortunately, it is the urban poor who suffer the brunt of poor water quality and lesser quantity as also in terms of burden of diseases. Further, the findings reveal urban diseases are strongly related to environmental hygiene. In this highly contested urban space with a complex socio-political environment, we need an alternative.

To tailor interventions and monitor progress for better urban health, the research advances to document and visualise existing micro-level information, to start with. Such an approach should take advantage of new technologies (GIS and mobile technologies) to harmonise sector-wide information, improve communication and advocate for improved urban health through free flow of information among various stakeholders.

Government agencies should rope in various educational institutions to document and upscale this information. This information could be shared with various stakeholders to communicate the health risks, thereby ensuring transparency and accountability. This will help government agencies to introduce stronger regulations and civil society could be mobilised to actively participate for efficient integration of water system planning and demand forecasting, design centralised and/or decentralised water infrastructure, and to improve public health.

The new government offers hope, by renaming (for political reasons) the JnNURM with a focus on use of latest technologies (including geospatial tools) and by giving priority to ‘housing for all’ by 2020. The speedy implementation of the national urban health mission, launched in 2013, is expected to improve urban health care and to work out institutional synergy with urban authorities.

The government is planning to invest about '7,060 crore to build 100 smart cities. Will the new government live up to the expectations of the rapidly urbanising economy? Can investment contain the urban ecology that is creating conducive environment for diseases?

Saravanan is with the Centre for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn, Germany.

The story appeared in the August 16-31, 2014 issue of the magazine.