Publication of a selection of articles from the venerable EPW is a cause for celebration

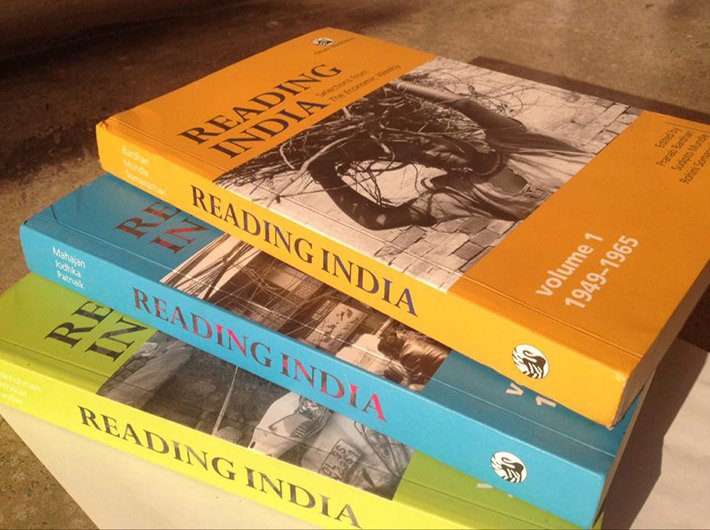

Reading India: Selections from The Economic Weekly, Volumes 1/2/3

Edited by Pranab Bardhan, Sudipto Mundle, Rohini Somanathan (Vol 1), Gurpreet Mahajan, Surinder S. Jodhka and Ila Patnaik (Vol 2), and Pulapre Balakrishnan, Suhas Palshikar, and Nandini Sundar (Vol 3)

Orient BlackSwan, 448 pages/ 486 pages/ 552 pages, Rs 695/ Rs 745/ Rs 795

Politicians call for it, editorialists call for it, but often it is not clear what it exactly is. What is a national debate? Shouting matches and scripted dramas of prime-time television certainly do not constitute a debate. The venue for right debate is expected to be either parliament or the edit page of the select few newspapers. The first, however, has limitations of time among other things, and the second has limitations of space – 1,200 words would be luxury. Amid ups and downs, new arrivals and departures in the publishing scene in India, two names have remained constant as the site of in-depth, impartial and well informed debates: EPW and Seminar.

The advantage with the EPW was that it was launched in in 1949, a decade before the Seminar, and close to the founding of the republic itself. Thus, its canvass has covered the spectrum of India’s colours in full chronology. It was launched as The Economic Weekly in a period that was “full of hope and expectation, but also questioning and rethinking. Under the leadership of its illustrious founding editor, Sachin Chaudhuri, the journal soon became a major platform for the finest minds of the time, providing a diverse range of scholarship and space for differing, often conflicting, ideological positions”.

It is reported that Jawaharlal Nehru, prime minister then, had left standing instructions the EW copy should go straight to his desk as soon as it arrived, notes Bardhan, Mundle and Somnathan in their introduction to the first of the three volumes that have put together a representative selection of articles from seven decades.

When Chaudhuri died in 1966, the baton was passed on to Krishna Raj, and it was around this time that it acquired the new name. Raj edited it for about three decades more. In recent times, it was helmed by inimitable C Rammanohar Reddy, followed by Pranajoy Guha Thakurta for a short while, before the current editor, Gopal Guru. Amid the changes, the journal has maintained its quality with incisive and illuminating analysis. For some of the best minds in the country (and abroad), it has been the first choice for publishing their essays. All the Nobel Economics Prize winners associated with India – Amartya Sen, Angus Deaton, Abhijit V Banerjee, and Ester Duflo have written for the EPW. Other contributors include Dr Manmohan Singh as well as Jagdish Bhagwati, Arun Shourie as well as Mani Shankar Aiyar, and Ramachandra Guha as well as Amitav Ghosh – not to mention Kaushik Basu, Romila Thapar, Jeffrey Sachs, Prannoy Roy, T.N. Srinivasan, Subramanian Swamy, Christophe Jaffrelot, Jean Drèze, and Andre Beteille.

Students and scholars earlier used to get their hands dusty scouring old EPW files in dingy corners of the university library. Digitisation has changed it; now old articles can be accessed with ease. Journalists and avid readers have joined them in waiting for Saturday mornings, when the new weekly edition goes online.

Of course, making a selection available in book form is a welcome move. The project had three panels of three eminent experts, selecting articles from periods 1949-1965, 1966-1991, and 1991-2017, to produce three volumes. The initiative, of course, faces the daunting challenge of what to include and what to leave out. The editors of the first volume acknowledge that this is bound to be an idiosyncratic selection, but it is hoped that it captures a flavour of the EPW.

Each volume presents the selections around broad themes of economics, policy, society and so on. The first volume opens with the classic ‘The Social Structure of a Mysore Village’ by M N Srinivas. Other authors include Bernard S Cohn, Iravati Karve, Andre Beteille, Rajni Kothari, Ghanshyam Shah, Nirmal Kumar Bose – and that is only the first of the nine parts of the volume.

The second volume begins with Rajni Kothari’s oft-quoted study, ‘India’s Political Transition’, and includes Arun Shourie’s critique of the control economy among other notable articles. The third volume has Ramachandra Guha tracing ‘Prehistory of Indian Environmentalism: Intellectual Traditions’, and includes Dharma Kumar’s ‘Left Secularists and Communalism’, Tanika Sarkar on ‘Vande Mataram’, A G Noorani on films and free speech, Amartya Sen’s ‘The Three Rs of Reform’ along with G Haragopal’s critique of it, and concludes with Akeel Bilgrami’s ‘Secularism: Its Content and Context’.

Given the extraordinary richness of the EPW archive, any selection is bound to leave some or the other reader unsatisfied. In terms of authors: Ramachandra Guha on challenges of contemporary history or on the bilingual intellectual generated much enthusiasm in recent years, but he has 62 articles in this journal so far! G P Deshpande was a regular contributor, writing on a broad range of topics from China to the question of classical language. Amid writing his seafaring tales, Amitav Ghosh delivered a gem of an essay, ‘Of Fanas and Forecastles: The Indian Ocean and Some Lost Languages of the Age of Sail’. Rajmohan Gandhi’s critique of Arundhati Roy on the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate, and her rejoinder too, found place – where else but – in the pages of the EPW. In terms of themes, many have been left untouched, from Gandhi to literature to climate change.

This is not pointed out as complaint, of course. And, yes, the cream of the EPW back issues has been made available in book form even earlier, with the thematic selections on caste, water, rural India, social policy, higher education, environment, sectarian violence, women, adivasi question and so on published by Orient BlackSwan [https://www.epw.in/book-store]. So, on the positive side, there is still scope for several more theme-based selections.

Meanwhile, the reader should not complain: there is a rich source material on the debates that shaped India since Independence, all put together in three well produced volumes.