The ivory white monument of love is turning pale yellow, and mudpacks are being applied to improve it. But is that enough when the cause of the yellowing is rampant pollution?

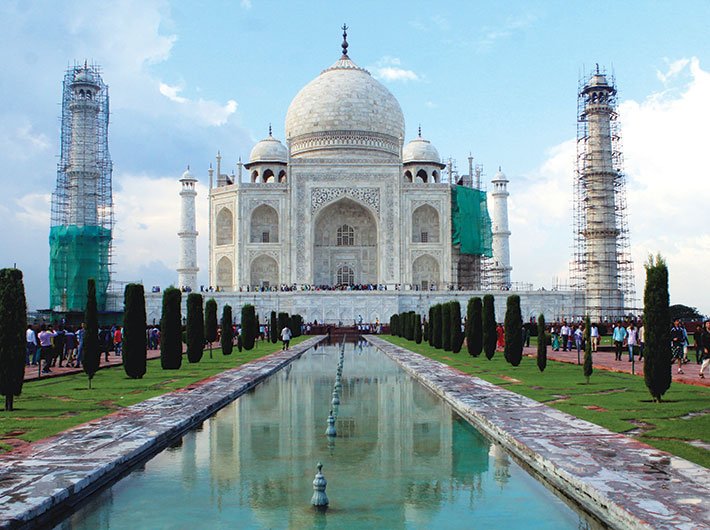

Patch by patch, the lucent dome of the Taj Mahal is being plastered with a mixture of Fuller’s earth. It’s a treatment other parts of the monument of love – minarets, walls and pathways – have received over the years. These mud packs, of two millimetre thickness, are believed to take away the grime and restore the marble to its ivory whiteness. Since the 1980s, toxins in the highly polluted air have turned the marble a sickening yellow. The mud packs will help, providing a temporary makeover. Of course, it’s no permanent solution.

In addition to preservation and conservation of the Taj, restoration work has also been undertaken by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Its experts have been applying Fuller’s earth packs on the Taj since 1994. The marble mausoleum had been given this treatment several times in the past, including in 2001-02, 2008-09, 2012 and 2014. “But earlier, this mud pack was applied on minarets, the passage and the level from which the main dome rises,” says MK Bhatnagar, of the science branch of ASI, Agra. This is the first time the main onion dome is being treated with mud. Work began in April, and is likely to take a year to complete – though there’s a break for two months now. Scaffolds have come up for workers to climb and apply the paste; polythene sheets are being cling-wrapped on the paste to prevent it from drying up too soon; green nets have been spread to check the sunlight. When the layer of dried clay starts falling, the walls are washed with distilled water. “Fuller’s earth packs are quite effective, non-abrasive and non-corrosive. They remove sticky pollutant deposits on the walls and crevices of the monument. Once cleaned, the surface doesn’t require treatment for 6-7 years. This method has been successfully used in the UK and Italy,” says Bhatnagar.

The treatment does leave marble structures bright. But there are some who say it’s only a cosmetic process. Prof R Nath, a historian and founder of the Brij Mandal Heritage Conservation Society of Agra, says he’d warned the ASI that applying Fuller’s earth would only deface the monument. Brij Khandelwal, a journalist and environmentalist who is a member of the society, says that Fuller’s earth would make the marble patchy.

There’s also criticism from those involved in tourism. “People come here for pictures,” says Vishal Khandelwal, a photographer and social activist. “If the dome is covered in scaffolding for a year, it will hit tourism.” The peak tourism season is from September to March, and since the work could take up to April next year, this year’s business is more or less ruined, according to those in trades and services associated with tourism: photographers, guides, money-changers, hotels and restaurants, handicrafts and so on.

There’s also criticism from those involved in tourism. “People come here for pictures,” says Vishal Khandelwal, a photographer and social activist. “If the dome is covered in scaffolding for a year, it will hit tourism.” The peak tourism season is from September to March, and since the work could take up to April next year, this year’s business is more or less ruined, according to those in trades and services associated with tourism: photographers, guides, money-changers, hotels and restaurants, handicrafts and so on.

The root cause

The experts who commend the Fuller’s earth treatment are well aware that it’s the conservation equivalent of symptomatic relief. The cause of the Taj’s discolouration is heavy air pollution – from heavy traffic, from the many factories and industrial plants in the Taj trapezium zone (TTZ), from the glass factories, from the many petha (candied gourd, synonymous with Agra) makers, who release smoke in the air and dump the residue from petha-making directly into the Yamuna. There are brick kilns that spew smoke and soot in neighbouring Firozabad and Mathura, and there’s an IOC refinery in Mathura, which spews sulphurous fumes. A few of these units have been shut down – but only on paper.

Municipal solid waste (MSW), which includes everyday items like polybags, plastic items, newspapers, clothes and rotten food, is also increasing the pollution and damaging the Taj Mahal. Instead of being properly disposed of, much of the MSW in Agra and in the neighbouring districts of Firozabad, Mathura and Gwalior is being burnt in the open. Agra alone burns a shocking 223 tonnes of MSW daily on average, which is 24 percent of the total waste generated in the city, according to a report prepared by a team of American and Indian scientists. In comparison, the national capital Delhi burns 190-246 tonnes of MSW on average, which is only three percent of the total MSW generated, reveals the report published in the journal Environmental Research Letters in 2016.

“Our study basically looks at emissions from burning of municipal waste and cow dung cakes in Agra. These two are the factors that can damage marble to the maximum extent than any other factor excluding vehicular and factory pollution. We found an acute rise in organic aerosols near Taj, especially carbonaceous one. Dust is another factor for the discoloration of the monument. Too much of vehicular pollution and continuous felling of trees in TTZ are also responsible for yellowness,” says professor SN Tripathi from the civil engineering department of IIT-Kanpur’s Centre for Environmental Science and Engineering. Tripathi was one of the members who prepared the study.

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) criticised the UP government over dumping of solid waste in the Yamuna near the Taj, commenting that the state was unable to protect a monument from which “it is making millions”. Since 1996, stiff measures have been taken by the government to slow down the Taj’s discoloration. In its first order, it completely banned coal fired power plants and coke industries in the city. It also ordered the relocation of over 400 brick kilns in and around the city. The district administration’s crackdown on the petha industry and the ban on burning of cowdung cakes for cooking were some other attempts.

Refinery woes

The issue of pollution around the Taj has its roots in the 1973 decision to set up a petroleum refinery at Mathura, some 58 km from Agra. In 1981, based on the reports of committees that looked into the pollution threat, the government closed down two thermal power plants in Agra and started using diesel as fuel in its railway shunting yards. In 1996, the supreme court ordered the establishment of the TTZ, an area of 10,400 sq km around the Taj Mahal, for strict enforcement of environmental rules to ensure its better conservation. The court also ordered that there would be no further expansion of industries in this area, covering five districts of Agra region and comprising of over 40 protected monuments including three world heritage sites – the Taj Mahal, the Agra Fort and the Fatehpur Sikri complex.

(Several parts of the mausoleum, especially those facing the Yamuna, have developed tiny crevices, which are invaded by the insects that leaves them stained with greenish poop)

(Several parts of the mausoleum, especially those facing the Yamuna, have developed tiny crevices, which are invaded by the insects that leaves them stained with greenish poop)

“But on the ground, things haven’t changed much,” says Shabi Haider Zafri, one of the members of the committee set up by the court to monitor the implementation of its directives. He joined the post around a year ago after the death, in 2016, of DK Joshi, a renowned environmentalist committed to protect the environment in Agra. For Zafri, Agra is more dusty, noisy and ugly today than it was 30 years ago, when Joshi started a movement to secure the historical monuments of the city from air pollution. For Zafri, a lot has to be done before “one can say Agra has become environmentally safe for the Taj Mahal”.

According to Zafri, over 20,000 saplings were planted in the Taj Nature Walk a couple of years ago. “Hardly any survived. Five thousand saplings were planted when the then Pakistan president Parvez Musharraf visited Agra [in 2001] and I can’t see any of those plants now. Saplings that were planted in TTZ during construction of Agra-Lucknow expressway and Yamuna expressway are not visible anywhere,” he says. Expressing concern over the increasing population in the city, he says that in the last decade, the city touched the 30 lakh mark, with more vehicles and waste heaps around the monument.

And as population increases, construction has had to keep apace. And instead of stopping construction of high-rises on the banks of the Yamuna near the Taj Mahal, the Agra Development Authority has gone on a house-building spree with Phase-1, Phase-2 and now Phase-3. “If the scenario remains same, you will see a grey Taj Mahal in half a century and may be a black one in another 100 years,” says a former ASI chief of Agra on condition of anonymity.

The bugs

Many parts of the monument have occasionally turned green, especially parts facing the Yamuna. According to the ASI, pollution in the Yamuna is to blame: the green colouration is actually a bug’s poop. “It’s because of pollution and pools of stagnant water. The Yamuna has turned into a breeding ground for a specific type of insect that is turning the white marble green. After several chemical and biological tests, the insect was identified as Chironomus calligraphus (Goeldichironomus),” says Bhatnagar. Several parts of the mausoleum, especially those towards the Yamuna, have developed tiny crevices, which are invaded by the insects that leaves them stained with greenish poop.

The ASI report, which has been shared with the government and all concerned authorities, states that due to low water level in the Yamuna, on whose bank Taj Mahal is situated, the area has turned into a swamp. This has accelerated the heavy algal growth and phosphorus contents in the water. This is the primary food for Chironomus calligraphus. It has been suggested that the Yamuna be desilted near the Taj to prevent stagnation. “Even after sharing the report with the government last year, nothing has been done till now. What was more shocking was that we were told to keep cleaning the Taj. Wo bole aane do keede. Aap bus ssaf karte raho. (They said, let the insects come and you keep cleaning),” says an Agra ASI official on condition of anonymity.

In the ASI report, the reason given for the high levels of phosphorus in the river is the practice of dumping the ash from bodies brought to Mokshadham, a cremation ground. The other reason cited is that when sluices of the Mathura dam are shut, the water flow stops, and the industrial waste dumped into the Yamuna, especially that from the leather and petha industries, stagnates. And indirectly causes damage to the Taj.

Crematorium and Hindu sentiments

In 2016, the SC had ordered the replacement of all conventional crematoriums near the Taj Mahal with cleaner electric ones. A similar order had been given by the court in 1998, but the UP government and the Agra civic bodies had replied that it was not possible to shift the crematorium – they said that according to some unofficial records, the crematorium was in use much before the Taj was built!

Environmentalists say the smoke is affecting not just the marble of the Taj but people’s lungs too. “Heavy pollution is caused due to these open pyres at the crematorium. Besides releasing harmful gases, the process also emits heavy metals. Mercury filling in teeth, for instance, when burnt could prove to be hazardous to people in the vicinity,” says RK Upadhyay, former professor of chemistry, Allahabad University, who is based in Agra after retirement. Attempts to move the crematorium elsewhere have been met with stiff resistance from locals, who claim the move will hurt their religious sentiments.

“It’s a very sensitive issue,” says Gaurav Dayal, district magistrate, Agra. He says the administration is trying to persuade people to switch to electric cremation and efforts are being made to upgrade the already existing electric crematorium adjacent to Mokshadham.

The staff of Mokshadham, however, vehemently deny all charges of pollution. “Can you imagine that we are causing pollution by burning ghee, camphor, sandalwood in the pyres?” asks Sanjay Singh, manager, Mokshadham. These things are instead helping enrich the environment by killing bacteria in the air and also produce good smell, according to him. Scientists at the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), Pune, which keeps a tab on the pollution status near the Taj Mahal, have offered a solution. Padma Rao, senior scientist at the institute, has recommended that crematoriums that use electricity and biogas should be used in Mokshadham. But her advice is hardly followed.

Apathy everywhere

So far, the government oversight has only made things worse. In fact, the SC recently berated the Uttar Pradesh government for the shoddiness shown in the repair work of the monument. “[Your] engineers should be ashamed of themselves,” said the court, while commenting on the quality of construction of roads in Taj’s inner circle, ring road and other areas that lead to the monument. It further stated, “People from all over the world come to see the monument and any construction done near Taj should be as good as Taj. You messed it up. It is unacceptable.” It could be due to administrative ineptitude or a lack of environmental regulation, with every passing minute this teardrop on the cheek of time is witnessing damage, sometimes repairable and sometimes irreparable. “If the Taj Mahal is to survive or return to its former glory, then bold new solutions are needed, and needed fast,” says ADN Rao, ASI’s counsel.

(Photo: Manoj Aligadi)

(Photo: Manoj Aligadi)

Even the willingness of officials to preserve and conserve Taj is hardly visible. Commenting about the ban on burning cowdung, AK Anand, former head of the pollution control board (PCB) in Agra, says that every step is being taken to stop people from using cowdung cakes but if they use it inside houses, the PCB doesn’t have any way of stopping it. “Even after the ban on autos on MG Road, Agra’s main road, these vehicles can be seen as there is no strictness. Plantation drives are being carried out, but with no pressure on the maintenance of the planted saplings, there is only decrease and no increase in green cover in TTZ. The issue is with enforcement, not with efforts,” says Rao. He also says that most of the time, the ASI is struggling to deal with silly court cases, petitions and issues that are hardly of any benefit.

“DK Joshi was fighting to stop the dumping of garbage in Yamuna. This is really important as we really need water in Yamuna. It will not only help in protecting Taj from bugs and damage, but also give government an opportunity to start night viewing of the Taj from Mehtab Bagh,” says Rao, adding that no one is bothered to concentrate on the real issues and officials are usually busy struggling with something unimportant. “One can easily save Taj by just managing garbage dumping and recycling, controlling vehicular pollution and creating awareness among residents. The Taj’s yellowness is not a technological problem but actually a managerial problem,” says Prof Tripathi of IIT-Kanpur. When it comes to meaningful solutions, Tripathi believes the government has fallen short. “The authorities need to concentrate on all sectors which are responsible for the air pollution, transport, household, MSW, commercial industry, etc,” he says, while adding that a strict clean-fuel policy for all public and private vehicles should be enforced in Agra.

Above all, regular monitoring and upgradation in policies is the need of the hour. “We do not bath one day to remain hygienic. We do not exercise one day to remain healthy and we don’t even eat one day to satisfy hunger. Then why we make policies one day and never look back on their implementation and the situation at ground level. This is a major problem in the system,” he says.

Nothing to see

When asked what Taj Mahal means to him, 72-year-old Tahiruddin Tahir recited two lines: “Baadshah bhi dikhta hai. Dada bhi dikhta hai. Mehboob bhi nazar aata hai… Ye Taj hi mujhe sabka deedar karata hai (I can see the emperor. I can see my grandfather and my love. This Taj makes me see all in itself).”

Tahir claims his forefathers have been taking care of the Taj Mahal since generations. He lives in Tajganj area that surrounds the 16th century monument of love, which was described as a “teardrop on the cheek of eternity” by Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. Tahir, who owns a shop selling marble inlay artifacts, also heads the Khuddam-e-Roza committee (comprising traditional caretakers of the Taj Mahal) which offers a long multi-colour chadar – representing different faiths of the country – at the grave of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan during the Urs (birth anniversary) festival.

Around eight million visitors flock the marble mausoleum, surrounded by tall minarets, lush green gardens full of trees and the Yamuna flowing at the back, every year. But this monument of love is now at risk of being defaced forever, says Tahir. “Dense smog, created by human activity, has turned the bright white Taj a pale yellow. Besides the airborne impurities, the monument is also at risk from human vandalism, insects from the dirty Yamuna and callous attitude of the government, which has allegedly failed to address the concrete issues while exploiting tourism opportunities,” he says. The situation seems unlikely to change. All the more tragic for a monument as grand as the Taj!

ishita@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the September 30, 2017 issue)