It’s a shame that the oppressive practice of bonded labour persists in the 21st century

In 1865 the thirteenth amendment to the US constitution abolished slavery and the buying and selling of humans, and soon the transatlantic slave trade declined. But a century and a half since, slavery persists across the globe in giant proportions and insidious forms. The International Labour Organisation estimates that 40.3 million people are enslaved, and 75 percent of them are in the Asia-Pacific region.

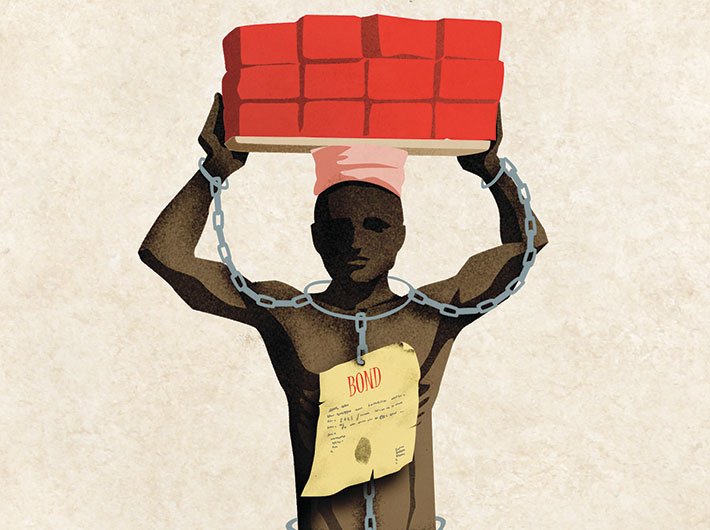

Among the widespread practices of slavery is that of bonded labour, seen in India and other subcontinental countries. It’s an exploitative, venal way of abusing for profit the labour of others. The borrower works off his debt, but, being illiterate and innumerate, he often has no clue about the interest rates, the payment cycles, how much he has repaid in labour, and how much remains to be paid. The terms of the loan are crippling, and the borrower and his family end up working all their lives without being paid for it, the womenfolk doubling up as farmhands and household help, often sexually exploited. They are usually put to work on farms, construction sites and orchards, and in brick kilns, garment factories and carpet factories. This is the unorganised sector, where deals are by word of mouth, safety is thrown to the wind, work hours are long, living conditions are appalling, meals are inadequate, and discipline is often enforced through violence.

A Global Slavery Index estimate from 2016 tells us that 18.3 million people, including children, were in modern slavery in India that year; in the same year, the National Crime Records Bureau data shows that 15,379 people were trafficked. Of the 23,117 individuals rescued from trafficked situations that year (including people who may have been trafficked in previous years), 10,509 had been compelled to work under oppressive forced labour arrangements.

Those trafficked and put to work at brick kilns and sweatshops in India are almost always lured by the promise of well-paid work. (This also applies to Indian workers trafficked to the Gulf and other regions, where, on entry, their passports are seized to dispossess them of their identity proof and mobility.) Many enter into bonded and forced labour systems with volition – but without foreknowledge as to what abuse is waiting for them – because of debts they took. The debt might be taken to meet the expenses of a wedding, a funeral, or to meet another similar social or community obligation, and always paid at exorbitant rates of interest – between 24 and 36 percent. It could be taken to pay for a medical emergency, to start a small business, to build a house. In any case, the debt is repaid in labour rather than in money. The creditor decides the terms of repayment, including the monetary value of the labour that the debtor performs. Thus the period of time he will have to stay bonded to the creditor, paying compound interest and principal at a rate set by the creditor – is also decided by the latter.

As a bonded labourer, the worker loses ownership of his work and of any products he makes with his own hands. He is prohibited from accessing any labour market where he can claim minimum wage, or showcase his products for sale at market value. Effectively, he becomes chained to the locale where his servitude has been established. He can escape neither his debt, nor the conditions of repayment that have been designed at great cost to him.

Sometimes, an employer, usually a manufacturer of some sort, will promise an advance to large groups of people if they migrate to work at a distant kiln or factory. When they have reached the destination, they are given only a small living allowance for food and other essentials, and immediately set to long and gruelling hours of work. In the absence of paperwork to corroborate the verbal contract, they are unable to claim the lump sum, their annual or biannual wage.

In bonded labour systems in India, some creditors, as employers consistently take advantage of workers’ ignorance and many vulnerabilities to manipulate credit histories so the labourer, and sometimes his entire family, can serve him as low-cost or free human resource inter-generationally. They deny their workers safe work environments, health benefits, any social security, and any shred of consideration for their comfort or welfare. Women in bonded labour are subjected to routine sexual exploitation; children, as they work alongside older members of their families, are forced to give up their rights to an education.

Over 18 million people live this life in India. That figure represents 1.4 percent of the nation’s population. They exist, after a fashion, in docile tolerance of shocking abuse.

The Bonded Labour (Prevention) Act of 1976 criminalised all forms of forced and bonded labor in Indian territory, and wrote off currently held debts. Interestingly, there were already precedents to this piece of legislation in the constitution. Article 23 prohibits all variations of bonded labour systems, whether the victim has migrated as a result of his enrollment in a bonded labour system or not. Article 21 also proffers the right to personal liberty to all Indian citizens, an entitlement bonded labourers have to forego once they commit to working at a set place for an indefinite period. With the 1976 statute, a scheme was developed to facilitate the rehabilitation of workers rescued from bonded labour setups, which has been through multiple revisions; the most recent version of the scheme is dated 2016.

The 2016 Centrally Sponsored Scheme for the Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers brings into the open significant observations on existing structures of debt bondage and forced labour operating in eight Indian states, including Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, where disadvantaged groups are at high risk of lapsing into bonded labour arrangements, or to be trafficked for exploitative work (not including commercial sexual exploitation). The document comments on problems in implementing existing legislation for the benefit of those trapped in bondage, and makes recommendations to resolve these.

Unsurprisingly for an Indian context, inefficient law enforcement appears to be one of the reasons why bonded labor continues to be a problem that governing bodies have to grapple with. In the four decades that have passed since the Bonded labour Act came into force, both the push and pull factors – fulfilling normative imperatives, wanting better lifestyles, and going after larger opportunity – that drive India’s chronically poor into debt, thence into debt bondage or other forced labour conditions, have not changed as much. It follows causally, then, that the same mechanisms that were employed through the first half of the twentieth century to reap fiscal profit off the labour of others are being used today, and history is repeating itself in the narratives of victimhood of exploited workers. Male heads of families are lured into bondage, women and children follow suit. Families from weaker economic classes continue to send children out to work to supplement family income. To break the circle and contrive proper prevention measures, the socioeconomic mainsprings that trigger people’s entry into bonded labour need to be identified and addressed.

The Bonded Labour Rehabilitation Scheme has provisions for non-cash assistance (though all rescued workers receive cash compensation) for rescued labourers, including affordable credit, seeds, and a supply of farming implements and animals. Most freed labourers have not received these goods. The International Labour Organisation has observed that district-level Vigilance Committees (appointed under the scheme) meant to identify and rehabilitate bonded labourers do not take their duties seriously enough. Cases against employers are dropped in favour of settlements made out of court; this essentially means that the employer can walk away with impunity and the newly freed serf jeopardises his own prerogative while contributing to the gap between what policies intend and what happens in practice.

The new Trafficking of Persons Bill 2018 makes special note of trafficking for the purpose of forced labour, and categorises it as an aggravated form of trafficking. It is important to note that the labourer in question, say, a labourer who enters into debt bondage with a landowner from his own village or district, will still be counted as a victim of labour trafficking despite the fact that he does not migrate, because once the motive of the recruiter – here, the creditor – has been established to be that of exploitation, we have a clear-cut case of a trafficking offence based on section 370 of the Indian Penal Code.

The Trafficking of Persons Bill 2018 is slated for discussion in the Rajya Sabha’s winter session, and if passed, can prove to be a crucial milestone in the campaign against trafficking as an organised crime in general, and unethical and exploitative bonded labour systems in particular. Coupled with the Bonded Labour Prevention Act and implemented squarely, there is chance yet for hoping that modern slavery will crumble to release millions into freedom and dignity.

(The article appears in December 31, 2018 edition)