Railway budget has proposed nine bullet trains. How feasible and viable is the proposal?

Neelesh Shukla, 50, lives in Mathura and works with a private company in Delhi. Around 9 every morning, he takes the EMU train from the city station to begin the 140-km journey over a couple of hours. Packed like sardines is the usual phrase to describe the passengers on such ‘local trains’ but on early July 1, as the humidity level in the national capital region threatened to keep pace with Mumbai’s, the sweat of fellow passengers is the only constant in Shukla’s mind.

To divert the mind, he strikes a conversation with a co-passenger. For a start, Shukla is not angry with the railway fare hike, announced on June 20. His only concern is whether the additional revenue generated would be used to upgrade railway infrastructure – used, especially, to start work on the project closest to his heart since Narendra Modi became the prime minister: bullet trains. Life, Shukla tells the co-passenger, would be a breeze then.

Four days later, Shukla’s dream comes somewhat closer to earth when the railways test-ran a semi-bullet train between Delhi and Agra on July 4. The 200-km journey was completed in about 90 minutes, with the train clocking a top speed of 160 km per hour (kmph) – 10 km more than the previous record.

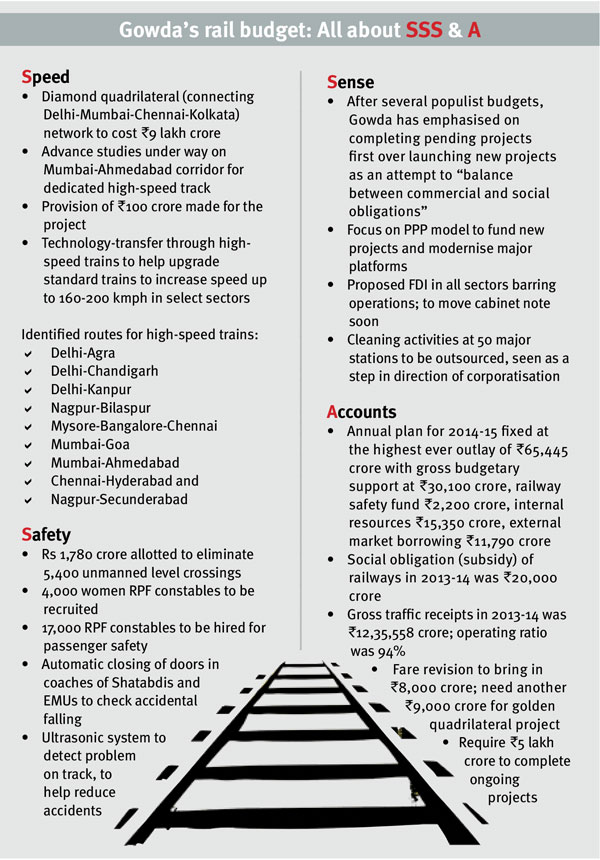

On July 8, as the Modi government presented its first railway budget, with railways minister Sadananda Gowda unveiling, among others, plans to start the first bullet train on the Mumbai-Ahmedabad route and presenting a proposal to start similar high-speed trains on eight other sectors, Shukla would have been on cloud nine while returning home – crushed in the rail coach – in the evening. Shukla’s son studies law in Faridabad; he undergoes a similar daily ordeal.

Life would be a breeze for thousands of inter-city commuters once the government puts on track the speed plan: high-speed (250-350 kmph) or semi-high-speed trains (160-250 kmph).

While the government is planning to build a diamond quadrilateral (connecting Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata) through these trains, measuring, in all, 10,000 km, the job, if it gets implemented, would be anything but a breeze.

While the NDA blames populist schemes of successive ministers like Lalu Yadav, Nitish Kumar and Mamata Banerjee for running the Indian railways to the ground, the track record of earlier projects – dedicated freight corridor, modernisation and electrification, among others – leave enough room for doubt. Many view the bullet trains as one of Modi’s many highfalutin plans, with little scope for such big-ticket projects being flagged off when the coffers are empty.

Even the US, this section contends, has put brakes on expanding its bullet train network.

Possible, achievable

Vivek Sahai, a former chairman of the railway board, the top decision-making body of the railways, believes the comparison between India and the US is not correct. “(US president Barack) Obama had announced the launch of high-speed trains in 2009. But then nothing much happened because bullet trains are very capital-intensive. Some Chinese and French studies show that you have to have 10 million passengers on each track every year to break even. That’s why only two or three lines are making profit even in China. But it is workable in India since we have the volume (of passengers).”

Explaining the difference between demand for high-speed trains in the two countries, Jaijit Bhattacharya, partner (infrastructure and government services) at KPMG in India, says the US is an automobile-based economy. “For them, it made more sense investing in roadways for shorter distances and in airways for long-distance travelling. India is a different case,” he says. “We have the volume here and the roadways are in a bad shape; even non-existing in many areas.”

But such a project, says Sahai, needs a man with a “heart of steel”. Seventy-five percent of success in such projects depends on the leadership. Then, “of course we need to have a strict deadline,” he says. It needs to be executed in a highly professional manner – like Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC) did – because the venture is so capital-intensive that delays would lead to cost overruns, which will kill the idea before it begins, Sahai says.

“If we are serious about it, the decision needs to be taken fast,” Sahai says. “It needs a strong leadership to roll out such a project. DMRC became a success story only because of E Sreedharan (the ‘Metro Man’ who was DMRC’s chief from 1995 to 2012). He had the guts to go against the railway board’s suggestion to run Delhi Metro on broad-gauge tracks. But Sreedharan fought against it and opted for standard gauge against the entire administration without wasting any time.”

For the record, Indian trains run on 1.6-metre gauge compared to 1.4-m standard gauge used worldwide.

Some sceptics also contend that the terrain and ground texture would make bullet trains a pipe dream in India. But Sahai laughs off such arguments and puts forward the example of Konkan railways. That, he says, was a difficult terrain to run trains on but it became the country’s only profitable railway segment. An underground metro railway network, he says, was called impossible but the DMRC did it.

Similarly, bullet trains are “technically feasible in India”. The only requirement: the tracks would require concrete reinforcements, like in any other country, he points out.

Bhattacharya, too, rubbishes the apprehensions, calling it just an “engineering issue”: “If a high-speed train needs a 4-inch concrete bed in Europe, make it 8 inches here if the soil is loose. This is how it has been done in other countries.”

Hurdles on the tracks: finance

Experts say financing – or getting loans – “should not be an issue” for the project if there is a decisive leadership at the helm. After the success with Delhi Metro, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is working as the funding agency for the Mumabi-Ahmedabad high-speed rail project.

The Indian railways should aim for soft loans for such projects, as it did in the case of Delhi Metro, Sahai says.

More important is time, he says. Borrowing money is getting expensive every day and bullet trains being a capital intensive project, if the government invests in it, it needs to get fast returns. That, however, would be possible only if the project is completed on time. Otherwise, its fate would be same as that of usual railway projects: the money would be locked, there would be cost overruns and low returns, and then the government would keep subsidising only to keep it running. And in that case no private or foreign entity would be interested in investing, experts warn.

If the government can replicate the professionalism shown in the case of Delhi Metro in the upcoming Mumbai-Ahmadabad high-speed corridor, both private players and foreign investors will jump in. JICA and the World Bank have already expressed interest in pouring money in India’s high-speed trains project.

JICA is carrying out a feasibility study on bullet trains in India. Refusing to give details, a JICA spokesperson says, “The study is at a very initial stage and is due for its completion in July 2015. We choose not to comment on anything before the study reaches its conclusion.”

Cost of speed

Manoj Singh, advisor (transport), planning commission, says the cost of running bullet trains is six times that of a standard train. “Running a bullet train would cost '100 crore per km. But that should not be a problem if we are determined to build the project,” he says. “The cost of underground metro was '200 crore per km. But we did it.

“India has the volume to make bullet trains profitable even at this high cost. The Delhi Metro is a live example before us.”

The union government can only help build the projects, but the day-to-day operational cost needs to be recovered from the passengers, Singh says, adding a rider: “These projects need to be run professionally and can’t be subsidised.”

What is important is pricing, Singh says. If pricing is competitive vis-a-vis flights, even 20 trains can be run at night and cut short the journey on the Mumbai-Delhi route to, say, between six and seven hours. That, incidentally, is the approximate point-to-point (home to destination, including journey to and from airports and wait at the airport) time taken by a flight journey.

So the challenge, former railway board chairman Sahai says, is to keep the ticket rates competitive.

Bhattacharya of KPMG concurs: “We should be bold enough to try new business models. As an example, Delhi Metro has one of the lowest metro fares in the world and is still operationally profitable, unlike most other metro (networks). Similarly, it might be possible to have a low fare and yet high-speed railway which becomes financially self-sustainable from an operations perspective if we choose the correct segment.

“High-density business traveler segments such as Mumbai-Ahmedabad or even Mumbai-Delhi could perhaps be the most appropriate segments to have high-speed railways in India.”

Sahai says India need not replicate every international model. “We can run trains at 250 kmph instead of 350 kmph considering our requirement. If the cost of running a 250 kmph train is '1 crore, it is '3 crore for 350 kmph,” he says.

Experts say the competitive fares could be compensated by revenue generated from other avenues. “In a preliminary study conducted by KPMG, it turns out that it is a challenge to have a financially sustainable high-speed railway (system) in India, taking into consideration the high cost of land. However, the projects start becoming sustainable when the value of the impact corridor is factored in and the impact corridor is monetised.”

‘Impact corridor’ is a term used for commercial assets along with the stations and tracks – like Delhi Metro has advertising boards, food courts, shopping plaza and office space that add to its revenue significantly.

Aim first for shorter distances

Since bullet trains are capital-intensive projects, experts advise starting them on shorter, 300-500 km distances before the government puts in place a plan to connect the four metropolitan cities. India is set to have its date with bullet trains with the Mumbai-Ahmedabad train covering 500 km – and that’s what the aim should be initially.

These shorter distances are not profitable propositions for air operators and railways can exploit them, giving immediate return on investment, experts say. Singh says, “Worldwide, our assessment is that if you analyse the traffic it is 80 percent bullet (train) and just 20 percent flight if the distance is up to 500 km. So (since) volumes will not be an issue in India, that’s why the government is first looking at shorter distances.”

What makes bullet trains imperative

The impact of a bullet train is somehow equivalent to the impact of saving the tiger, according to experts. Saving only the tiger does not entail wildlife preservation. But by saving the tiger, it is imperative that the whole ecosystem is saved, which in effect ensures that other wildlife also get saved.

Similarly, implementing the bullet train network would ensure an upgrade of the whole system, policies, procedures, human resources and organisational restructuring that is essential to run a modern railway system. The spin-off effects of bullet trains on the conventional system areas are very significant, Bhattacharya reasons.

Another red flag put up by critics is the energy issue. They contend that high-speed trains need enormous energy, which would not be good news for an already energy-deficient country. Agreeing that energy consumption of high-speed trains is higher than that of standard trains, Singh, however, says, “Per capita energy consumption is less than flight. It (also) makes great sense from the environment point of view, and that’s why governments worldwide are envisaging these trains.

“Even small countries like Morocco, Malaysia and Vietnam are mulling on getting these trains.”

Experts also point out that being a greenfield project, it would be easier to build the bullet train network than semi-high-speed trains, as brownfield projects would be relatively difficult considering the traffic volume.

Although it is difficult to assess its impact on the GDP at the moment, experts say the high-speed train network will help in rapid urbanisation and industrialisation. New cities and business hubs will develop along these corridors, which will have a rub-on effect on the overall economy. The cost of building these networks can be recovered hypothetically, they say.

The project will also have a rub-on effect on the railways as a whole, helping in technology sharing and upgrade of the creaking railway network. It would also decongest other routes and increase safety measures on existing tracks, experts say.

“We cannot make one initiative dependent on another. That way, India will never become competitive and will always play catch-up with globally competitive economies. We must implement modernisation of conventional railways and implementation of high-speed railways simultaneously,” Bhattacharya says.

The government is exploring both the public-private partnership (PPP) model and foreign investment, along with soft loan from global finance organisations, to start these projects.

Railways: from 28 kmph to 50 kmph in 161 years

India’s first train ran on April 16, 1853, carrying 400 passengers and covering the 34 kilometres between Bombay and Thane in about 75 minutes at a speed of 28 kmph. After 161 years, an average train in Mumbai runs at an average speed of 50 kmph.

In 66 years since independence, India has added 13,000 km of new tracks. China added 14,000 km in just 5 years between 2006 and 2011, according to an Ernst and Young report.

Indian railways carries around 23 million people every day. A 2012 government report put the number of annual railway-related deaths at 15,000.

In 2012-13, railways reported losses of Rs24,915 crore.

(The story appeared in the July 16-31 issue of the magazine.)