Mr Moily, you were right. There are import lobbies at work, but they are not the only ones. If you just look around in your ministry, and those of your cabinet colleagues, you will find different import, export, domestic, political, private sector, public sector, and economic pressure groups lurking in almost every corridor of power

“Masochist”, claimed a column in Business Standard, as it explained the attitude of the government to consistently attract controversies. “Mind-boggling foolishness”, said another piece uploaded on www.firstpost.com. Both the articles took cue from the government’s latest “reforms” move to double the domestic price of natural gas to $8.4 from April 2014. The decision was taken despite the opposition from some cabinet ministers, including the petroleum minister, M Veerappa Moily, himself.

Moily, in fact, had earlier sensationally claimed that he, like past ministers, was threatened by “import lobbies”, which did not want the Indian government to take decision to “cut down imports” of oil and gas. He said this at a press conference in the context of why the country had to increase local gas prices to attract investments in the exploration sector. His rationale was that if the foreign investors get a good price, they will pump in money as India was “floating in oil and gas”.

However, Moily had hoped that the cabinet would increase the gas price by around 50%, and not 100%. Does this imply that UPA-II avoided the pressures of the import lobbies as it hiked gas prices, but succumbed to the influences of the “domestic lobbies” that wanted the prices to double, rather than go up by only 50%? Whether Moily likes it or not, domestic energy prices are invariably determined by powerful political, business, diplomatic, legal, economic and global lobbies. These groups force India’s hands, both overtly and covertly, when it comes to pricing of the fuels.

Here is an attempt to explain the role of these lobbies, and how they impact the decision-making process. If we just consider the recent hike in gas price, one can understand how Moily’s claim about import lobbies was only partially correct, and was only the tip of the iceberg. Here’s why:

Politics behind gas prices

One constant refrain that one hears in the present context is: why did the government take the decision to double the gas price almost a year in advance? Why couldn’t it wait till early next year, as the price had to be reviewed in the case of some domestic producers only in April 2014? The single-word answer to such questions is: politics. Clearly, there were lobbies within the government, as well as within the Congress party and its allies, which wanted the decision to be taken NOW.

The thinking within these political sections was that if the government waited too long, it wouldn’t be able to act at all. The reason: if the decision was postponed till February or March 2014, the election commission (EC) could have stalled it. The EC rules state that major policies can’t be announced once the assembly or national election phase kicks in, which is either three months before the elections or after the EC announces the poll dates.

Since the national elections are scheduled by May 2014, the risk of EC’s intervention went up substantially if the hike was delayed until early next year. Another fear amongst the pro-hike groups was that the government may be forced to opt for early national elections in November or December this year. In such a scenario too, an announcement now was a better alternative. The main interest of these lobbies was to boost the profits of select gas exploration firms in India.

One has to remember that several months ago Arvind Kejriwal of Aam Admi Party (AAP) alleged that the former petroleum minister S Jaipal Reddy was shunted out because he had opposed the increase in gas price. Kejriwal maintained that the hike was demanded by Reliance Industries, one of the largest gas producers in the country. Therefore, one can assume that the pro-hike political lobbies were earnestly at work for some time to benefit certain gas companies.

Legal issues behind gas prices

The website, www.firstpost.com, which is “published by Network18, whose promoters have received funding from the Reliance (Industries) Group”, has made an insidious argument several times. According to its logic, gas prices cannot be decided by a government committee, bureaucrats or the cabinet. “The only move that can be called reform is market-based pricing – where businesses take both the risks and rewards of global and domestic price movements,” said one of its recent pieces.

Such an argument has two inherent and critical flaws. The first is that the supreme court in its 2010 judgment had set down the ground rules on how the gas price can be fixed. The order argued that natural resources, whether under the ground or over it, are owned by the citizens of the country. Therefore, only the government can decide both the price of natural gas and the manner in which the discovered gas can be allocated to the different user industries (like power, fertilizers and steel).

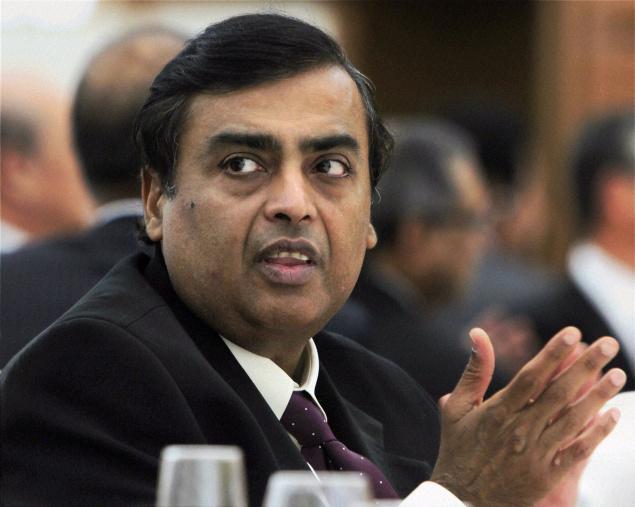

In the case of gas, the court concluded that the price would be decided by the ministers and bureaucrats. Ironically, it was Reliance Industries, which argued in favour of government intervention in gas pricing in the supreme court. In the same case, the company, whose promoter, Mukesh Ambani, fought against his younger brother, Anil, had maintained that the contract signed with the government did not leave any scope for market pricing.

The second flaw in the market-based price thesis is that it intrinsically implies that the domestic price should be linked to the international price(s) of natural gas. If this contention was taken to its logical ends, the cabinet should have fixed the domestic price at $10-12, and not $8.4, or a further increase of 19-43%. Thus, if the government had followed the advice of www.firstpost.com, Reliance Industries, as also other local gas producers, would have benefitted further. We know that in India, companies do not reduce the local price if global price goes down, but they are among the first to hike it in case they go up.

Import lobbies behind gas prices

Moily obviously did not realise the implications of his disclosure about the threat from import lobbies. The biggest lobby that argues for and supports gas imports comprises the government-owned companies such GAIL and Petronet LNG; the official line is that Petronet LNG is not state-owned, although 50% of its equity is held by four oil and gas PSUs, including ONGC and GAIL and its chairman is generally the highest-ranked bureaucrat in the petroleum ministry.

Around the time that Moily sensationalised the issue, his bureaucrats told the media that the government wished to import an additional 20 million tonnes per annum of gas, over and above the 15 million that it imports today. They added that India was the fifth largest gas importer, and there were plans to increase the capacity for re-gassification (gas is generally imported in liquid form and then re-gassified at domestic terminals) from 13.6 million tonnes per annum to 50 million tonnes by 2017.

In the recent past, GAIL has announced its intention to double gas imports, and the PSU has signed agreements for fresh supplies with two US firms, and also has an existing contract with Russia’s Gazprom, which will supply gas from 2019. GAIL plans to build a new re-gassification terminal in Andhra Pradesh, apart from its existing one in Maharashtra. Petronet has inked gas deals in the US, and the ministry has sought for higher and new supplies from Qatar and Australia, respectively.

What Moily forgot was that gas imports are mostly finalised at the bilateral level through negotiations between the Indian government and the supplier country. This was the case with Qatar, which is among the leading supplier to India. In addition, it is always the intention of the Indian government to source gas from friendly nations such as the US, Canada and Australia, apart from Qatar. In the past, discussions with not-so-friendly nations such as Pakistan and Myanmar have not proceeded well. Logically, the Indian government can be construed to be a part of the import lobbies.

Diplomacy behind gas prices

As mentioned above, diplomacy and international relations play a crucial role in gas imports as most of the deals are negotiated at the bilateral level. In the recent past, Qatar, which sits on cheap gas sources, has put pressure on New Delhi to increase its purchases. In fact, Qatar agreed to supply gas at rock-bottom prices to India. The Indo-Qatar agreement for gas supplies was one of the important ingredients that prompted the government to hike gas prices now.

The contract between Qatar and India stated that the latter would pay international (higher) prices for gas from 2014 onwards. This meant that the government had to take hard decisions, or else there would be a huge mismatch between the price of imported gas and that of locally discovered sources. This would have led to market distortions, and Petronet’s inability to sell the higher-priced gas. As the government was unsure about elections – they may be held in November 2013 or May 2014 or any time in between – it took no chances and announced its intention to hike the domestic price to peg it nearer to the global price.

If, as stated above, GAIL and Petronet source fresh gas supplies, they would have to buy it at the higher international prices ($10-12 or whatever the price would be when they sign the final purchase agreements). New imports from the US are from shale gas sources, which too are expensive. To sell additional quantities, GAIL and Petronet would have to find consumers in 2014 and 2015, if the supplies commenced in 2016 and new re-gassification plants were built by 2017. Not many consumers would have paid a higher price, if the domestic price remained at $4.2.

Business lobbies behind gas prices

For years, Reliance Industries was at the forefront to lobby for a higher gas price. The reasons were simple: forced by circumstances, its promoter, Mukesh, had agreed to supply huge quantities of gas to the state-owned NTPC and his younger brother, Anil, at ridiculously low rates. The company wanted to wriggle out of these commitments and, in 2010, the supreme court decided in its favour. The government played its part earlier and allowed Reliance Industries to charge $4.2, instead of the promised $2.34. However, Mukesh wasn’t satisfied as global prices were higher.

Later, Reliance Industries put pressure on former petroleum minister, Reddy, to agree to a further hike. Reddy was removed, and Moily took his place. The Rangarajan committee on gas prices said the new price, applicable from 2014, should be $8.4. In a bid to nip the gas controversy in the bud, especially after Kejriwal’s allegations, Moily pushed for a workable solution or for a price midway between $4.2 and $8.4. It was then that he came with his explosive statement on import lobbies.

However, both private- and public-sector lobbies continued to influence the government. With support from key government agencies and ministries, like the planning commission, they succeeded even though at least three powerful ministries (petroleum, power and fertilizers) were against such a huge (100%) hike. Moily, in fact, became the joker in this game, as he publicly said that the government was likely to agree to price of around $6.5, and not the Rangarajan formula.

National interest behind gas prices

Big business houses in India play set-piece moves when they wish to curry huge favours from the government. In general, the trick is to convince the media and public that the government’s decision was in “national interest”. The late Dhirubhai Ambani, the father of Mukesh and Anil, perfected this art into a science in the 1980s and 1990s. Each favour that was doled out to Reliance Industries, or its sister concerns, was always in public and national interest. It was billed as a favor to the consumers.

Today, the government too has become adept at this play. When the gas price was increased to $4.2, it was not done only for Reliance Industries. Even the non-NELP gas price, i.e., gas discovered in fields that were allotted before the government came out with its new exploration licensing policy in the late 1990s, was increased to $4.2, which meant huge benefits to state-owned entities like ONGC. Thus, the logic was that the move helped mostly government-owned firms.

In the present case, when the price has doubled, it was applicable to all companies that produced gas, including Reliance Industries. Yet again, it was ostensibly aimed to help public sector units. But the critics argued that it would harm state-owned firms in the power and fertilizer sectors, which would have to pay a higher price and, finally, hurt the consumers and farmers who would have to pay more for electricity and fertilizers. So, finance minister P Chidambaram took a curving free kick.

He explained that while the price which the exploration firms will earn, or output price, has been decided by the cabinet, no decision has been taken on what the user sectors like power and fertilizers will pay, or the input price. “What is the price at which it (gas) should be supplied to a power plant, to a fertilizer plant, in order to make power affordable, fertilizers affordable… that can still be decided between now and April 1 (2014),” Chidambaram told the media.

This argument, to any sensible person, would seem like another illogical one in order to suit certain pressures, lobbies or interests. Mr Moily, you were right. There are import lobbies at work, but they are not the only ones. If you just look around in your ministry, and those of your cabinet colleagues, you will find different import, export, domestic, political, private sector, public sector, and economic pressure groups lurking in almost every corridor of power.