It would not have come to pass if we were not seen to be weak, indecisive and incapable

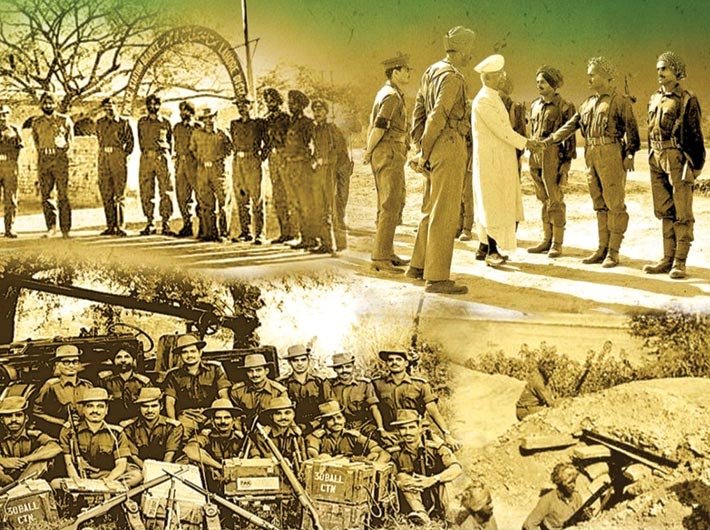

The preamble may just put you off but let me make a positive beginning. There is no doubt that we won the war that was thrust upon us; we disallowed Pakistan from achieving its aim of wresting J&K and destroyed the bulk of its modern weaponry. Our prime minister made bold decisions on the basis of military advice proffered to him, even as we fought passionately with antiquated equipment. Yet, that takes away nothing from the fact that the war was thrust on us by an incorrect perception that Pakistan was allowed to carry and build to its folly.

The beginning of the 1965 war lay in the perception of India’s military weakness in the wake of a glaring defeat at the hands of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1962. It can also be traced back to the 1950s when the foundation of modern India was being laid. The military was just kept out of the ambit of nation building. Perhaps, somewhere existed an impression that the Indian armed forces were loyal to the imperial masters and never partook in the national movement.

On the other hand, across the border, Pakistan was preparing itself for the eventuality that it may have to go to war to wrest areas which it perceived it had been denied during the partition.

Having denied a rightful place in the security hierarchy and a voice in national security considerations, the much weakened Indian army lost the border war of 1962. Between 1962 and 1965, and with the 1950s in recall, the state of the Indian armed forces was abysmal. Hurried attempts to raise new formations were underway. In two or three years, modern equipment does not flow nor can a military absorb all that.

The military was also in a state of shock after its defeat and was just emerging from it. To top it, the economic situation in India wasn’t too good with crop failures, and dependence on the US food aid programme doing no good to the nation’s self-esteem. The crisis of the theft of a single strand of the Prophet Mohammad’s beard from the Hazratbal shrine in J&K had been so politicised that Kashmir was still reeling under turbulence. To add to this, language riots had broken out in Tamil Nadu; the state of unity wasn’t much to write about either.

Nehru died a broken man on May 27, 1964, and his successor Lal Bahadur Shastri did not inspire confidence by either his personality or demeanour. For Pakistan, this was a major indicator of the ‘time being ripe’. There were other happenings such as Pakistan’s outreach to China, India’s nemesis, and the illegal ceding of 5,000 square km of territory in the Shaksgam valley with the hope that China would embroil India in the eastern front, while Pakistan would do its bit in the west. It was a smart strategy and has paid Pakistan dividends over the long term. While Pakistan did not have China’s nod to initiate hostilities, it perceived that it had China’s tacit support.

The last of the important observations about the run-up to the war relates to the Ayub-Bhutto-Musa trio; Ayub was then president of Pakistan, ZA Bhutto the foreign minister and Mohammad Musa the army chief. Bhutto convinced Ayub about the ‘now or never’ situation. The fatal advice which Bhutto gave was also related to the appreciated capability of PM Shastri to extend the war to Punjab and Rajasthan borders, if Pakistan initiated it in J&K. He said that was impossible; the PM did not have the strategic courage and his military advisers were still probably suffering from the hangover of defeat. On the basis of this advice, which apparently General Musa’s better military sense did not endorse, the Pakistan army did not even cancel the leave of its soldiers once India crossed the ceasefire line (CFL) in J&K on August 26, 1965.

Operations in Brief

Wars between neighbours usually start with the testing of waters which was done by Pakistan in Kutch and Kargil, two extreme ends, where it undertook operations from April to June, 1965. The Bhuj stand-off involved aggressive patrolling, evicting Indian troops from Kanjarkot, and capturing Sardar post occupied by Indian forces in 1956 and four other posts in the same area. In Kargil, extensive shelling commenced along the CFL in January 1965. In May, the Indian army recaptured Pt 13620 and Black Rock, two features which had been occupied by the Pakistan army along the Dras-Leh road. A brokered ceasefire by the British government brought an end to hostilities on July 1 but Pakistan appeared to perceive a victory. There was a self-delusional belief about the superiority of the Pakistani soldier vis-à-vis the Indian jawan.

Operations Gibraltar & Grand Slam

J&K was the objective and Pakistan’s diabolical plan under Operation Gibraltar was to infiltrate a couple of thousand regular soldiers, along with locals, from PoK into J&K in the form of irregular forces akin to Lashkers that had been employed in 1947-48. From Gurez in the north to Naushehra in the south, they were to penetrate, engage rear areas, destroy infrastructure and logistics installations, severe the national highway and get to Srinagar to declare the Revolutionary Council of J&K having taken control. This was to be followed by Operation Grand Slam, an armoured-infantry thrust to capture the strategic town of Akhnur, along with the iron bridge over river Chenab, thus effectively cutting off Poonch and Rajouri from Jammu. That was about all; it was J&K centric with the presumption that the Indian army would never have the courage to extend the war to Punjab and further south. Of course it needs to be mentioned that Pakistan did perceive the full support of the major Islamic countries and of the US, being a partner under the alliances SEATO and CENTO.

Indian intelligence had failed to pick up activity of recruitment, training and creation of the Gibraltar force. The intelligence bureau (no R&AW at that time) was still smarting under the failure of 1962 when the Gibraltar force was launched from August 5, 1965. In the bargain, first reports of presence of these elements were from Bakarwals (shepherds) in the higher reaches. Rapid engagements followed but there was a dearth of troops for reaction; an additional brigade was rushed to the valley but obviously infiltration could not be controlled. The intended occupation of Srinagar, the airfield and the radio station did not materialise. Significantly, the people of J&K did not support the infiltrators. Identifying the core center of Operation Gibraltar, lying in the central area of Haji Pir Bulge, had the Indian army advising PM Shastri of a riposte leading him to state, “India cannot go on pushing the Pakistanis off its territory. If infiltration continues, we will have to carry the fight to the other side.” Operation Bakshi was launched on August 26, 1965 from Uri and Operation Faulad from Poonch. The critical Haji Pir Pass fell into Indian hands on August 28 through a coup de main by Major Ranjit Dayal (decorated with Maha Vir Chakra and rose to a Lt General) of 1st PARA and consolidation continued over the next 10 days.

Sensing the dwindling fortunes of Operation Gibraltar, Ayub authorised Musa to launch Operation Grand Slam for the capture of Akhnur, on September 1, 1965. It was designed to capture crucial territory and create a criticality for the Indian troops south of the Pir Panjal. Indian intelligence again failed as concentration of two armoured regiments and move of 7 Pak Division opposite Chamb-Jaurian in Akhnur sector could not be picked up. Facing Pakistan’s forces was a weak squadron of tanks and an infantry battalion. The initial operations were undertaken by two Pakistani brigades but both failed to cross Tawi river on the first day – September 1. It probably instigated a change of command with the Pakistan army chief flying into the battle zone and replacing Major General Akhtar Malik with Major General Yahya Khan, GOC, 7 Division. Yahya took a tactical pause of 24 hours thus allowing the Indian army to reinforce Akhnur, the one major factor which changed the course of the operations and destinies in the battle in the sector. Akhnur could not be captured but instigated a response leading to launch of a counter offensive into Pakistan’s Punjab province; it was an operational necessity.

India launched an offensive in Punjab on September 6. Jalandhar-based 11 Corps worked on a three-pronged offensive across the Amritsar IB towards Lahore achieving complete surprise. The success brought the Indian army to the anti-tank obstacle of the Ichogil Canal and crossing over it was secured. However, there was no plan to exploit that and had to be subsequently vacated. There was good reason for 11 Corps not to overstretch itself as further inroads would have embroiled it in the built up area of Lahore, which any operational commander would avoid. Penetration to Burki, along Khalra–Burki axis, and the capture of even Dograi was achieved. Yet, it was equally important that the flanks be secure especially as the whereabouts of Pakistan’s main formation, 1 Armoured Division, was not known.

Pakistan responded with its 11 Division and 1 Armoured Division in the south at Khem Karan in an attempt to turn the Indian flank. Major tank battles ensued with the Pakistan armour, and its modern Patton tanks bogged in the quagmire created by the bursting of canal bunds and wet soil of the monsoon months. However, the virtual turning movement attempted by Pakistan was a major threat to the Grand Trunk Road and the possibility of Pakistan being able to cut off Amritsar which would have forced India’s 11 Corps to withdraw to the security of the line of Beas river. The army chief, General Choudhry, apparently did order that but it was Lt General Harbaksh’s dogged refusal which saved the day. Indian troops fought at Asal Uttar and created the Pakistan tank graveyard for which Company Quarter Master Havildar (CQMH) Abdul Hamid, 4 Grenadiers, posthumously won the Param Vir Chakra.

The second offensive was launched by 1 Corps on September 9, in the Sialkot sector opposite Jammu-Samba. Here, it was the lone Indian Armoured Division (First), which encountered resistance from Pakistan’s 6th Armoured Division, the existence of which was not known.

Once again, a hard slogging match occurred between the Pattons and India’s Centurions, and the lesser proficient Shermans at battlefields such as Chawinda, Phillaura and Buttur Dograndi. Splendid actions by Poona Horse of the Armoured Corps and 8 Garhwal Rifles (losing both CO and 2IC in a single battle) exemplified that the Indians had their basics right, knew their equipment with its limitations and upheld the spirit of their regiments. This front was a stalemate with losses to both sides. The second PVC was won by Lt Col AB Tarapore of Poona Horse. Deeper south in Rajasthan, neither side had the resources to exploit the ‘tankability’ of the desert. Yet, incursions by both took place at Gadra Road, Munabao and Miajlar with no major decisive results, although the intensity of fighting was high.

The Indian air force came into its own on September 1, 1965 and was involved less in counter air and more in counter surface force operations. With its antiquated Gnats, Vampires and Mysteres against the PAF’s modern F-86 Sabre jets and star fighters, it put up a splendid performance although its material losses were heavy and losses on the ground inexcusable. Operations in the east were avoided primarily to prevent any instigation of the Chinese. The navy had a very limited defensive role off the coast of Dwarka, as India was reluctant to take the war to the high seas and extend its ambit.

The ceasefire came under pressure of the UN Security Council. India accepted the condition of return to territorial positions of August 5, 1965. Although only 14 percent ammunition had been expended by India (against Pakistan’s few days left as balance) and the war could have continued, to force capture of more territory, India decided to follow its strategy of avoiding all-out war. In retrospect, some territory could have been gained and it would have been possible to bargain for retention of Haji Pir in PoK.

Lessons of 1965

It is reiterated that India won the war in terms of capture of territory, destruction of wherewithal and denial of intent. The armed forces learnt the major lesson that without modernisation of equipment and tactics, victory could be elusive; they were fortunate that they won simply because the ‘man behind the weapon’ in their case proved to be more dedicated and proficient. There were many other lessons but majorly four need to be mentioned here. Firstly, at the national level, it was the decisiveness of PM Shastri and his willingness to listen to military advice. This lesson was carried to the situation in 1971 when PM Indira Gandhi similarly accepted military advice from the army chief Sam Maneckshaw. It needs reiteration today as the armed forces once again are losing their place in the decision cycle of the government.

Secondly, there is no denying that in 1965 there was never any inter-service cooperation; it is still lacking although we have achieved much.

In modern warfare, no single service can ever win a war. Thirdly, the field of intelligence has come a long way. In 1965, we appeared to be surprised at most times. Today’s challenge in the complex irregular warfare is not just the pickups, but the timely dissemination to the user end and the willingness to consider it seriously. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly; if a nation gives the impression that it is weak and does not have the will to defend itself by audacious and aggressive response, it will always be targeted. India made the mistake of giving that impression in 1965. Hopefully it is not providing similar inputs today when Pakistan once again appears to be crossing the limit of our tolerance.

Fortunately, on September 6, 2015 – Defence Day (of Pakistan), is attracting mature and sensible writing from Pakistan’s civil society which accepts Ayub’s mistake and hopes Pakistan will not follow his example and remain prudent.

Lt General Ata Hasnain (veteran) is a former general officer commanding of the Srinagar-based 15 Corps, which fought the 1965 War in J&K. He retired as the military secretary of the Indian army. Currently, he is associated with the Vivekananda International Foundation and Delhi Policy Group.

(The article appears in the September 16-30, 2015 issue)