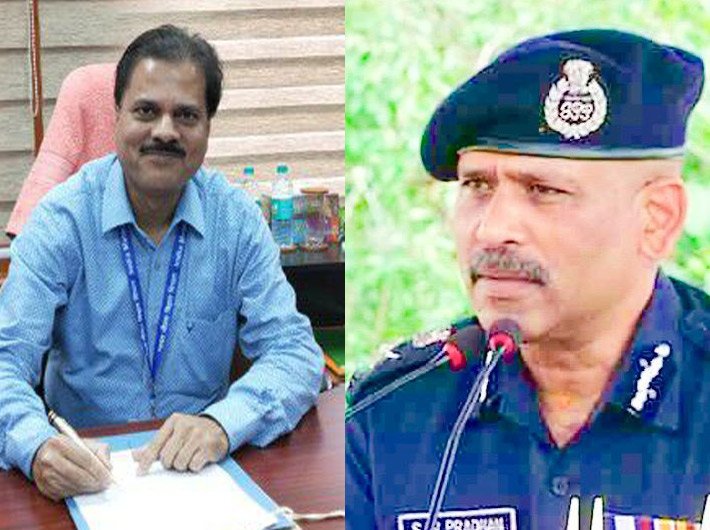

Met head Mohapatra and NDRF chief Pradhan share great rapport, join prediction with response

On May 19, India Meteorological Department (IMD) Director General (DG) Mrutyunjay Mohapatra followed his standard routine before a cyclone’s landfall: he had a series of meetings with experts, issued cyclone alerts, briefed media. Then, in his sixth-floor, corner-room office in Mausam Bhawan on Lodhi road in New Delhi, he spent the night, quietly tracking the movements of Very Severe Cyclone Amphan, which was to make landfall the next day.

“It’s a warlike situation. Pressure is intense on the night before the cyclone. We were alert every moment,” Mohapatra says.

An equally alert SN Pradhan, DG of National Disaster Response Force (NDRF), was in constant touch with his teams at Ground Zero – in West Bengal and Odisha – where the cyclone was headed.

“We are in operational readiness, on auto gear, always, and would swing into action and deliver the best, come what may. It’s our new normal,” Pradhan says, adding, “If NDRF doesn’t, then who?”

In between, Pradhan, a Jharkhand cadre IPS officer, kept enquiring, ‘Ladkon ko theek time par khana mil raha ya nahin’ (are the boys being served food on time?) “I get pictures of food served through WhatsApp from commandants,” Pradhan says, adding, “The culture of care is in built in NDRF. If you take good care of your internal constituency, they will do the same for the external constituency.”

Incidentally, both officers are from cyclone-prone Odisha and admittedly share a great personal and professional rapport.

Experts say cyclone response heavily depends on accurate prediction. Prediction and response are like the two sides of the same coin and both have a critical role in successful cyclone management. Not once but twice, within a fortnight, IMD and NDRF, successfully displayed their credentials as Cyclone Nisarga made its landfall near Mumbai on June 3 after Amphan’s near Sundarbans in West Bengal, two weeks ago. That too, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

They had done exactly the same in Odisha before and after Cyclone Fani of May 3, 2019.

“IMD and NDRF have been doing a splendid job. The country should be proud of Mohapatra and Pradhan,” says Aurobindo Behera, former IAS officer who headed Odisha State Disaster Management Authority (OSDMA) in its nascent years. Odisha is considered the pioneer in cyclone management in India.

The build-up

Though on May 1, Mohapatra got a hint from a model that a low pressure was going to be formed over the Andaman coast, which showed the nuances of turning into a cyclone-named Amphan, and it was confirmed that it had shaped into one on May 13. The same day after issuing the press release, at 3.30 pm, he conveyed to all field offices, through video conferencing, to ‘stay prepared.’

Radars were doubly checked to ensure that they were functioning properly and staff leave were cancelled as Mohapatra and ten experts manning the cyclone warning centre and the other 20 at the National Weather Forecasting Centre got down to business.

Recounting an incident post Cyclone Nargis (2008) in Myanmar, where he spotted an old man trying to set his ravaged thatched house into order, Mohapatra says, “Everyone wants to live. As weathermen, we must make accurate prediction and minimize casualty.”

Mohapatra, who has predicted several cyclones including Phailin (2013), Hudhud (2014), Fani and Bulbul (2019) with pinpoint accuracy, is credited with the transformation of India’s cyclone warning system. He is affectionately called the 'cyclone man of India.'

A cyclone, he explains, is a heartless killer. All its three stages – heavy rain, strong winds and tidal waves – are disasters in themselves; thus, a cyclone is a bundle of disasters.

Interestingly, with the monsoon approaching, the NDRF was prepared to meet a flood situation. Instead, two cyclones arrived first. “It was like an extended trial run for us,” says Pradhan.

Days before the cyclone’s landfall, India’s elite disaster response agency had deployed teams on ground in West Bengal (19 teams) and Odisha (20) where Amphan was headed. Later, 10 more teams rushed to West Bengal. In case of Nisarga, 43 teams had been stationed in Maharashtra and Gujarat. Post cyclone too, they worked round the clock, rescued those in peril, saved lives and assisted the local governments in restoration of communication and power.

For that, NDRF teams were equipped with, apart from chainsaws, tree-pole cutters, generators as well as satellite phones, wireless sets and other communication equipment. “We hope for the best, but prepare for the worst,” Pradhan claims.

Covid-19 challenge

Keeping the Covid-19 problems in mind, as early as from March, IMD had stopped taking upper air observation through balloons; it’s done in only 20 of the 56 field stations. These balloons are costly and often imported. The stocks saved proved handy during Amphan and Nisarga.

On the other hand, months ago, NDRF had a video conference with epidemiologists, procured dried (customized rainproof) PPEs and other essentials.

The pandemic created hurdles in everything, from forecasting - collection of data, analysis -to dissemination of information. “Our team had discussions over phone, each member worked overtime,” says Mohapatra. Experts were called in and made to stay in the guesthouse, while the National Media Centre was used for media briefing. Even journalists had to be briefed individually to maintain social distancing norms.

Usually, once the cyclone’s pressure is off, Mohapatra says he congratulates each of his team members individually, and they also organise a small party. “This time Covid prevented that,” he adds.

However, NDRF lacked such a luxury. According to Pradhan, the Force had realized soon that Covid-19 was going to be a ‘part of life’ for some more months, even years. Given the nature of their job, they were well aware of high risk of infection.

Incidentally, the ‘Men in Orange’, as the NDRF officers are called, have been pressed into the Covid-19 management too, from receiving passengers of the first flight from Wuhan, training over 80,000 professionals across airports, sea ports and borders on how to operate during the pandemic, to distribution of rations in cities, even in containment zones. And they have succeeded in their efforts.

However, success hasn’t come without a price. During the response to Cyclone Nisarga, two of its men suffered serious injuries – one of them had some of the fingers chopped by a chainsaw. Both are recuperating in a Mumbai hospital. Responding to Cyclone Amphan left at least 50 NDRF personnel with Covid-19 infection in West Bengal.

US-based celebrity chef, Vikas Khanna, who has been coordinating delivery of cooked and dry rations to those-in-need across 125 cities in India, is all praise for NDRF. Speaking from New York, he says, “They helped us reach out with dry rations to people in 15-16 cities, the entire logistics were taken care of by them efficiently. It was amazing, indeed.”

Khanna adds that by June 10 they have been able to reach out to approximately 12 million families. “Without Pradhan-ji and NDRF, we would have failed in this exercise,” he concedes.

Commending both IMD and NDRF, for their efforts, internationally acclaimed disaster management expert NM Prusty says the IMD’s smart forecast can be smarter by localizing weather data management. For some years Prusty, as head of the Indo-US bilateral initiatives on disaster management, had played a key role in IMD’s modernisation and NDRF’ institutional capacity building. He adds, “NDRF can make more impact by developing a seamless connectivity with disaster response forces at the respective state and community levels.”