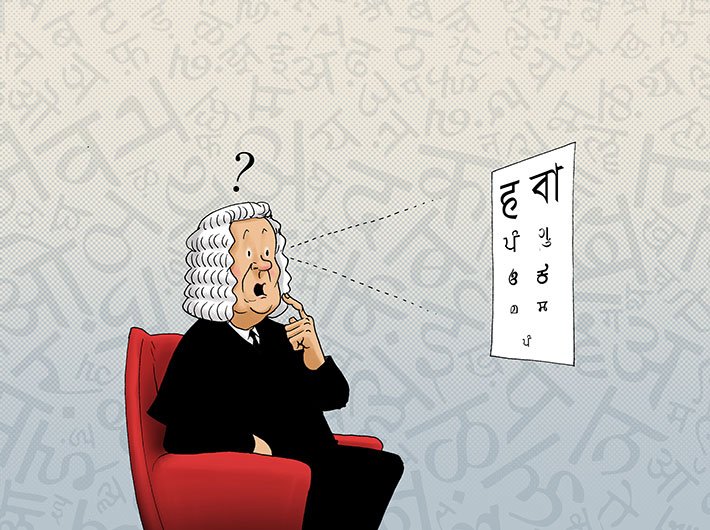

English as the lingua franca of the supreme court makes it inaccessible to the masses. It’s high time the judiciary went vernacular

I heard this interesting anecdote from a dear colleague in Lucknow, late Tahir Abbas. His father had attended a meeting addressed by Muhammad Ali Jinnah in Lucknow before Partition and returned quite dismayed at the great leader’s anglophile conduct. But the maulvis who attended the conference were quite impressed and heard saying, “Mian, Angrez bhi aisi angrezi nahi bol paate (Even Englishmen could not match his skill of speaking English)”.

True or not, there is little doubt that Jinnah’s linguistic skills, though largely incomprehensible for his target audience, ultimately endeared him to the Muslim clergy and masses that led to the division of the country. The moral of the story: in the Indian subcontinent the influence of English is far more pervasive and overweening than one believes.

Given this setting, chief justice of India Ranjan Gogoi’s rap on the knuckles on an additional district and session judge for his inability to speak in English did not come as a surprise. The details of the incident that took place in October are less relevant if we look at the larger picture, the language of justice.

It was of course not the first time the choice of language in conducting the business of the apex court made news. There have been umpteen occasions when some subaltern raises the issue. The maverick politician, Raj Narain, wanted to intervene in a case relating to socialist leader Madhu Limye, but the judges of the supreme court objected to his language, and his intervention was cancelled.

Of course, English is the official language of the supreme court. This stems from the constitution. Article 348 (“Language to be used in the Supreme Court and in the High Courts and for Acts, Bills, etc.”) states that “all proceedings in the Supreme Court and in every High Court … shall be in the English language.” This reflected the challenges, at the time of the constituent assembly debates, of building a nation in a multilingual setting. The constitution, however, has been amended several times over, and indeed for high courts a number of states have officially switched to the regional language after seeking assent of the president.

Also, Article 348 also mandates the use of English language for “the authoritative texts”, all bills/Acts of the central and state legislatures, as well as ordinances. But legislatures have moved on, and not only conduct the business in a variety of tongues, but the bills and Acts of parliament are published in English as well as Hindi.

However, even after seven decades of independence, India’s apex court has not only steadfastly retained certain colonial features but also successfully thwarted the process of democratisation within.

If parliament or state legislatures had retained those features and insisted on the primacy of English and put premium on the clipped accent of the speakers, India’s transition from Nehru to Lal Bahadur Shastri would have been impossible. No doubt, the legacy of the British Raj was so overpowering for decades that it was difficult for the institutions of the state to throw it off in a jiffy. Yet the democratisation of the polity ensured that the Indian legislature and the bureaucracy would gradually transform into multilingual entities in consonance with the features of Indian society. But the highest judiciary assiduously insulated itself from the process.

The apex court’s splendid isolation from the rest of the institutions of the state is often justified on assumption that the knowledge of law and its complexities flows from one’s ability to understand or speak English in the court. This and other such assumptions form the basis of the 216th report of the Law Commission, in 2008, whose very title is: ‘Non-feasibility of introduction of Hindi as compulsory language in the Supreme Court of India.’

The Committee of Parliament on Official Language has then proposed to amend Article 348 and dilute the English-only mandate. A reference was made to the Law Commission, which sought opinions of retired chief justices and judges of the supreme court, senior advocates and bar associations in different states. Based on the views of the fraternity, the panel recommended against introducing Hindi in the apex court (see box).

Among other things, the Law Commission report stated:

“At any rate no language should be thrust upon the Judges of the higher judiciary and they should be left free to deliver their judgments in the language they prefer. It is important to remember that every citizen, every Court has the right to understand the law laid down finally by the Apex Court and at present one should appreciate that such a language is only English.” (Emphasis in the original)

The case for English

What the law panel said in 2008

“The Commission has deeply gone into the views so obtained and has unanimously recommended that –

i) Language is a highly emotional issue for the citizens of any nation. It has a great unifying force and is a powerful instrument for national integration. No language should be thrust on any section of the people against their will since it is likely to become counterproductive.

ii) It is not merely a vehicle of thought and expression, but for Judges at the higher level, it is an integral part of their decision-making process. Judges have to hear and understand the submissions of both the sides, apply the law to adjust equities. Arguments are generally made in higher courts in English and the basic literature under the Indian system is primarily based on English and American text books and case laws. Thus, Judges at the higher level should be left free to evolve their own pattern of delivering judgments.

iii) It is particularly important to note that in view of the national transfer policy in respect of the High Court Judges, if any such Judge is compelled to deliver judgments in a language with which he is not wellversed, it might become extremely difficult for him to work judicially. On transfer from one part of the country to another, a High Court Judge is not expected to learn a new language at his age and to apply the same in delivering judgments.

iv) At any rate no language should be thrust upon the Judges of the higher judiciary and they should be left free to deliver their judgments in the language they prefer. It is important to remember that every citizen, every Court has the right to understand the law laid down finally by the Apex Court and at present one should appreciate that such a language is only English.

v) The use of English language also facilitates the movement of lawyers from High Courts to the Apex Court since they are not confronted with any linguistic problems and English remains the language at both the levels. Any survey of the society in general or its cross-sections will clearly substantiate the above proposition which does not admit of much debate, particularly in the present political, social and economic scenario.

vi) It may, however, be admitted that in so far as legislative drafting is concerned, every legislation although authoritatively enacted in English may have a Hindi authoritative translation along with the same at the central level. Same analogy may be applied even in respect of executive actions at the central level, but the higher judiciary should not be subjected to any kind of even persuasive change in the present societal context.”

Stoutly opposed

“I am of the firm opinion that the Constitution should not be amended to enable the Legislative Department to undertake original drafting in Hindi. I am even more stoutly opposed to the recommendation 16.8(e). Neither the Supreme Court nor the High Courts should be asked to deliver their judgements in Hindi. The judges of these courts are drawn from all over India and they are not all conversant with Hindi. The English language is now acquiring importance as the language of the world. We should not deny the new generation the benefit of English language.”

–YV Chandrachud, former CJI

Not by compulsion

“I am all for Hindi as a personal preference, but I am all against Hindi by compulsion, especially of judgments of the Supreme Court of India. I have many more reasons from a practical angle in support of the present system which I cannot elaborate here. … Wisdom is different from obscurantism. Let us give Hindi a high place in national expression and full facility for instant translation of every representation people wish to make to the higher courts as an integral part of free legal aid. The three-language formula which has some official status may well be considered for implementation, whatever be the cost it may involve. Linguistic militancy will alienate and divide but federal pluralism is democratic sensitivity.”

–Justice VR Krishna Iyer

Suicidal

“It appears to me that unless two generations of lawyers are trained to do legal transactions in Hindi, it would be suicidal to change the language of the High Courts and Supreme Court from English to Hindi. Further, the Supreme Court being composed of judges from different states, who may not be aware of Hindi at all, it would be next to impossible for them to conduct proceedings or write judgements in Hindi. In my considered view, the proposal to require the Supreme Court and the High Courts to deliver judgments in Hindi would definitely result in chaos and adversely affect the administration of justice.”

–Justice BN Srikrishna

Hasten slowly

“On the merits of the issue, one must acknowledge that Hindi as our national language must assert its rightful place in all areas of our national life and the higher judiciary should be no exception. The Committee of Parliament on Official Language has rightly emphasized the importance of this matter.

In the practical implementation of this philosophy, there may be some issues, arising out of circumstances that the legacy of the Common Law which we have inherited, the system of Public law, the International Human Rights regime, the International Intellectual Property regime and the increasingly integrating economic laws and trans-border transactions impose an integration with the legal systems of other countries and jurisdictions. All this may influence the policy of language in the superior courts. However we should respect the parliamentary views and a beginning has to be made through circumspection requires that we should hasten slowly.”

–Justice MN Venkatachaliah

Excerpted from the Law Commission report No 216

Ground reality, on the other hand, could not have been more contrary to this Macaulay-inspired position. Acknowledging every citizen’s right to understand the law laid down by the apex court is a praiseworthy sentiment, but English would be an inappropriate choice for the purpose. According to the 2001 census, India had only 2,26,449 people, or 0.02 percent of the total population, who reported English as their first language. Adding even those who claimed English as second language and also those who said it was their ‘third language’, the total still comes to barely 12.18 percent. Whereas Hindi, for example, covers 53.16 percent of the population considering all three types of speakers. Indeed, Hindi has the third highest number of speakers in the world (after Mandarin Chinese and English) but will remain sidelined at home. Of course, this is not to make a case for Hindi in particular, but for Indian languages in general.

Yet, the myth of the necessity of English in the judiciary is deliberately perpetuated to keep the portals of the higher courts as the exclusive domain of a privileged few who speak in a language incomprehensible to masses. The situation is reminiscent of the status of Sanskrit in religious matters: Hindu rituals are conducted only in Sanskrit and only the professional pandit can do so, whereas his client has no clue of what business is being conducted on his behalf. That might be the necessity of faith, but justice is not a ritual.

Unlike in religious matters, the language bar in courts comes with two costs. Firstly, it has raised the cost of justice so high that the higher judiciary is nearly inaccessible even for a reasonably rich man, let alone the common man. Secondly, the restricted pool of resources – judges and lawyers who can converse in Queen’s English – has led to a gargantuan pendency of cases, delaying and thus denying justice in a plethora of cases.

Remember the plight of a former secretary of the government of India, HC Gupta, who preferred to be in jail rather than paying a lawyer to fight corruption cases slapped against him by the CBI. His lament was simple: “I cannot pay the lawyer; so send me to jail and let me avoid ignominy of going through this process.” Gupta is known to be a rare bureaucrat with an impeccable career, without blemish, till the supreme court-mandated inquiry by the CBI in the coal scam implicated him.

Gupta’s plight is not an isolated case. Except for big corporate houses, bureaucrats with dubious credentials or politically high-profile cases, the exalted portals of the supreme court are prohibitively expensive to enter. It is well-nigh impossible for even a privileged middle-class Indian to hire a lawyer who can speak clipped English with sufficiently impressive academic background and genuine pedigree to plead for him in the country’s highest court.

Contrast this with the evolution of the legislature and the executive, and you would know the difference. In the early years of the republic, the elites in parliament and the executive found it easier to converse in English than an Indian language. But over the years Hindi and other regional languages contended for that space and enriched the debates by resorting to earthy wisdom of local tongues. The evolution of powerful regional satraps was related to the transformation that the Indian legislature had undergone due to democratisation. Leaders like Chandrashekhar, HD Deve Gowda, Atal Bihari Vajpayee or Narendra Modi may not speak English in an accent which is widely prevalent in Lutyen’s power circles but none of them found this a handicap in earning recognition of their leadership qualities. Similarly, the character of the bureaucracy has undergone complete transformation ever since candidates appearing for the civil services exams were allowed to take the test in their regional languages.

The rise of the subaltern in the legislature and the executive is frowned upon by the traditional elites as they found their erstwhile citadels thoroughly breached. That is why leaders who cannot speak English fluently like say Shashi Tharoor or Mani Shankar Aiyar are often mocked. But that hardly affects their politics. Modi, Lalu Prasad, Nitish Kumar, Mulayam Singh Yadav and Mayawati never vied for any endorsement from the India’s anglophile class to establish their political credentials. Ironically enough, Navin Patnaik who belonged to this elite class successfully de-classed himself (to borrow Marxist terminology) to launch himself in Odisha politics. They are big politicians in spite of this class. Similarly, there are few bureaucrats in the capital whose eloquence in English is their attribute for being successful.

But the higher judiciary has remained insulated from the rise of the subaltern.

It has also resisted reservation in judges’ appointment on the basis of social backwardness, a thesis which it endorsed for the bureaucracy. This is why the law ministry has often broached the issue of inadequate representation of women and various sections of society in the high courts and the supreme court. Similarly, the Right to Information (RTI) Act which is applicable to all institutions of the state is quite restricted when it relates to the higher judiciary.

In essence, India’s higher judiciary fits into a classical definition of “othering” the other institutions of the state, like the legislature and the executive, in “such a way as to reinforce and protect the self”. “Othering” is more about the self than others.

In the pre-independence phase, Mahatma Gandhi was conscious of this situation and tried to persuade Jinnah to converse in Gujarati – their common mother tongue – in order to make the latter to understand the spirit of India. Gandhi failed, and the result was obvious. Perhaps, the privilege that English enjoys in the higher judiciary needs to be diluted in order to make its portals accessible to those who speak languages different from the clipped and accented English of foreign-educated but exorbitantly expensive lawyers. The rise of the vernacular in the higher echelons of the judiciary is not only long overdue but also imminent. As only a constitutional amendment can launch the process of change, a renewed debate on the linguistic question – between the legal fraternity and the rest – is the need of the hour.

ajay@governancenow.com

(The column appears in November 30, 2018 edition)