Emerging evidence points to a parallel crisis: lead-induced anemia, often misdiagnosed as iron deficiency

In a village in Bihar, a mother brings her pale, lethargic child to a government health camp. A hemoglobin test confirms anemia. She leaves with iron tablets and dietary advice. Months later, the child remains unwell. What if the problem was never iron deficiency, but lead poisoning, silently damaging the child’s blood, brain and future?

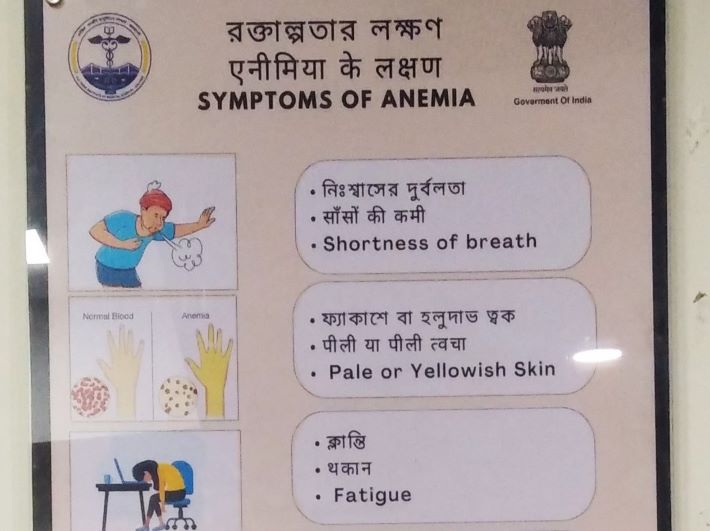

India has made notable progress in addressing childhood anemia. Programmes like Anemia Mukt Bharat and iron-folic acid supplementation under the National Health Mission reflect strong policy commitment. But emerging evidence points to a parallel crisis: lead-induced anemia, often misdiagnosed as iron deficiency.

Iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) and lead-induced anemia share clinical similarities. Both result in microcytic, hypochromic red blood cells, smaller and paler than normal. But the underlying mechanisms differ sharply. Iron deficiency arises from inadequate intake or absorption. Lead poisoning, by contrast, disrupts heme synthesis by inhibiting critical enzymes like Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) and ferrochelatase. It also damages red blood cells directly, reducing their lifespan and compounding anemia.

The interaction between iron and lead makes matters worse. In iron-deficient children, the body increases production of a protein called Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) to absorb more iron. Unfortunately, DMT1 also facilitates lead absorption. This means iron deficiency actually increases a child’s vulnerability to lead toxicity. Iron tablets may improve hemoglobin counts, but they cannot remove lead from the bloodstream or reverse its neurological damage.

Despite this, lead exposure is rarely considered in anemia diagnosis. Environmental health receives little attention in medical training. Most frontline health workers lack the tools to identify or test for toxic exposure. A 2020 report by UNICEF and Pure Earth estimated that 275 million Indian children have blood lead levels (BLL) above 5 micrograms per deciliter (µg/dL), the WHO’s reference level for concern.

India does not currently mandate BLL screening even in children with persistent anemia or developmental delays. Without routine surveillance or adequate diagnostic infrastructure, lead-induced anemia remains invisible in our health system. Children are misdiagnosed, mistreated and left to suffer the long-term consequences.

This demands immediate policy and clinical action.

First, India urgently needs to standardize BLL thresholds to enable consistent diagnosis, clinical intervention and public health surveillance of lead poisoning. Currently, there is no officially mandated reference value or treatment guideline, leaving clinicians and health workers without a clear framework for managing lead exposure, particularly in children.

BLL testing should be integrated into pediatric anemia protocols, particularly in high-risk areas such as industrial zones, mining regions and informal e-waste sites. District hospitals and primary health centers must be equipped with point-of-care lead testing tools like portable analyzers or dried blood spot kits. Frontline workers, including Anganwadi staff, ANMs and pediatrician smust be equipped to identify key signs of lead toxicity, such as persistent fatigue, irritability, growth delays and distinct physical indicators like the Burtonian line, a bluish discoloration along the gums, indicative of prolonged or chronic lead exposure.

Second, India must establish a National Lead Surveillance Programme. Just as we map diseases like malaria and tuberculosis, it is vital to identify lead exposure hotspots by integrating environmental and health data. This will enable targeted interventions and resource allocation in vulnerable communities.

Third, environmental toxicology must become a core part of medical education. The clinicians need to be well equipped to address the hidden burden of environmental exposures especially as industrialization and informal sectors expand across the country.

Fourth, India must align its threshold with international standards and strengthen regulatory oversight of lead in consumer products including cosmetics, cookware, toys, spices and paints. Regulating lead content in everyday items is essential to safeguarding public health and preventing long-term exposure.

Lead does not cause anemia but it often leads to its misdiagnosis. By interfering with blood formation, lead exposure can mimic iron deficiency. The symptoms seem familiar: fatigue, pallor, low haemoglobin. The prescription is predictable: iron tablets. But when lead is the hidden factor, this treatment misses the mark and the child continues to suffer.

This isn’t just a diagnostic error; it’s a systemic blind spot. A 2021 World Bank report estimates that India loses $236 billion every year to productivity losses from childhood lead exposure. That figure reflects not just economic damage, but futures dimmed and potential lost.

India’s nutrition-focused anaemia efforts have made progress. But unless we address environmental threats like lead, we risk treating numbers not children. Iron tablets can’t remove lead from the body. They can’t repair the brain. And they can’t prevent the harm we fail to see.

To truly protect our children, we must look beyond iron deficiency. Accurate diagnosis, lead testing in high-risk areas and clean environments must become part of our public health response. Only then can we claim a meaningful victory against childhood anaemia.

Dr Sahil Parmar is a Fellow at Pahlé India Foundation. Shreya Anjali is a Public Health Analyst at Pahlé India Foundation, and Sneha Chetri is a Research Associate at Pahlé India Foundation.

Photo Credit: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/Symptoms_of_anemia_are_written_in_Bengali%2C_Hindi_and_English_language_on_a_board_at_AIIMS_Kalyani_-_1.jpg