Just three players dominate the wireless market today. We look at how this came about, and what it means for the government, the banks, and consumers

Pratap Vikram Singh | November 3, 2017 | New Delhi

Over about a year, the number of telecom operators in India has effectively shrunk from 14 to three: Idea Cellular-Vodafone; Bharti Airtel and Mukesh Ambani-owned behemoth Reliance Jio – apart from the state-run BSNL/MTNL. Virtually every other operator has wound up. Tata Teleservices and Telenor India have merged with Airtel. Reliance Communications, belonging to Mukesh’s brother Anil, attempted a merger with another fading telco, Aircel, but the deal fell through, and there are unconfirmed reports that the latter is planning to file for bankruptcy. A desperate Reliance Communications is scrambling to find buyers for its mobile towers. State-run BSNL and MTNL find their subscriber base depleting: “They will meet the same fate as Air India,” says a former senior official of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI). “We’ve gradually moved towards a forced oligopoly; later, we may move to a duopoly.”

INTERVIEW: Drop in revenue is a temporary phase: RS Sharma, chairman, TRAI

Market analysts say that across the globe, telecom is an oligopoly market, and therefore it is good for India. It has of course been good for Airtel and Reliance Jio, whose shares have gone up. For the first time in eight years, Airtel’s share price on BSE rose to Rs 471 (October 22). It had dipped to Rs 293.50 in December 2016, a time when Reliance Jio extended its free promotional offers for another three months. Reliance Industries Limited, the parent company of Reliance Jio, was trading at Rs 904.

But there is a heavy burden of debt on all telcos, which have been borrowing largely from public sector banks to buy spectrum. The telecom players together have a debt of some Rs 4.5 lakh-crore, according to unofficial estimates. Airtel owes Rs 1 lakh crore to banks, Reliance Jio roughly Rs 1.10 lakh crore, Idea Rs 65,000 crore, Tata Teleservices over Rs 45,000 crore, Reliance Communications Rs 47,000 crore, and Aircel Rs 14,000 crore. Among all only Airtel and Reliance Jio are well-placed to service their debts.

According to market pundits, in the coming 12 to 18 months, the three major telecom operators would need to rationalise tariffs, which would improve the revenues of the operators and help Reliance Jio break even. The tariff war, intended to acquire more customers, would soon subside. The new race will be about retaining the subscribers. The industry, which faces a whopping debt of several lakh crores, would require annual investment on networks. According to an industry veteran, operators would need investment to the tune of Rs 30,000 crore a year to be able to reasonably maintain a hold over the market. Thus mobile bills are bound to go up.

Good talking times

For subscribers, FY 2016-17 has been a feast year. Reliance Jio made high-speed internet accessible and affordable in an unprecedented way. The bonanza for subscribers began on September 1 last year when RIL chairman Mukesh Ambani launched a meticulously planned promotion offer, giving voice free for life and 4G data at throwaway prices. For other operators, voice constituted 80 percent of the revenue, so with Jio’s entry, they ended up with 60 percent reduction in revenue. Shares nosedived within hours of Jio making an entry.

Jio bundled voice and data into a single tariff, with customers paying only for data. To keep their noses above water, the others are competing to bundle voice and data at tariffs less than Rs 300 per month. They are also offering tons of data and voice calling. In less than a year, Jio had added 130 million subscribers. Over the year, Jio users consumed a staggering 100 crore GB every month – that’s more bytes per month than the number of seconds since the Big Bang.

The long-term impact cannot be understood or predicted, but in the short term, it is going to be a phase of consolidation in the industry. Predatory price-cuts, such as those offered by Jio, will be over soon. Service quality, though, is problematic. Call drops are of epidemic proportion. And though the average speed of mobile internet has risen to 5.6 Mbps, often the high-speed network would struggle to deliver 2G speed in metros, leave alone rural areas. The latest Akamai report says only 36 percent of Indian internet users access internet with over four Mbps. This gives us the lowest rank, along with the Philippines, among 15 Asia Pacific countries featured in the report. For India, even today, the definition of mobile broadband is 512 Kbps, not 2 Mbps, as in many other countries.

“What consumers want is the right service at the right price. Not cheap service at a cheap price. What we are getting now is literally cheap! There are people in the market who are willing to pay the right price,” says a senior analyst at a renowned brokerage firm in Mumbai. The operators including Jio may have claimed in their ads that they were aligned with prime minister Narendra Modi’s Digital India initiative. “We are nowhere near the quality of service required for a real Digital India. India is a services based economy and it needs ubiquitous dependable information and communications technology infrastructure and services. Newer technologies and the need for higher data speed means that network infrastructure constantly needs to be upgraded whereas we already have high levels of debt in the industry,” says Arpita Pal Agrawal, partner and leader, telecom, PwC India.

Spectrum, a limited resource

Although industry veterans say consolidation was unavoidable given the fragmentation of the spectrum and the market, it has raised several other questions: how could the industry reach this pass? And what was the role of the regulator? For the record, the telecom sector is a cash cow for the government, a means to curb government’s fiscal deficit. (Even this is illusory, as some experts point out, but we’ll come to that later.) Critics have been pointing at the artificial curbing of spectrum supply by the government to increase the auction price for the spectrum (See box for revenue collections in auctions). The root cause of the mess was mindless offering of telecom licences during A Raja’s tenure as telecom minister in 2008-09. The number of operators in the sector went up to 14. Spectrum is a finite resource: the greater the number of operators, the smaller the size of spectrum-holding per operator.

Globally, the mobile sector has been working with limited spectrum. “You can’t keep on pumping more and more competitors. The less the spectrum per operator, the lesser the efficiency of the network. It means more towers, more interference in ecology. If you look around the world, the average number of operators in any regime is three to four,” says TV Ramachandran, president of the Broadband India Forum, and founding director general of industry body Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI).

Rightly so, when the TRAI was found in 1997 by an Act of parliament, a couple of functions assigned to the regulator were: “to make recommendations, either suo motu or on a request from the licenser, on...need and timing for introduction of new service provider” and “efficient management of available spectrum”. Thanks to the auction design, set by the regulator and the department, the bids have gone through the roof. The government and the industry both are equally to be blamed.

“Primarily the whopping debt of over Rs 4 lakh crore is because of the four-five auctions since 2010,” says a former senior government official, adding that it became worse with the disruption caused by Reliance Jio. “All they (operators) were doing is paying the government for spectrum after borrowing from public sector banks, filling the government’s budgetary hole. In effect, it seemed as if the central government was itself borrowing from public sector banks to cover the fiscal deficit,” says a former bureaucrat who has held top positions in telecom. “Whether it was Pranab Mukherjee or whether it is Arun Jaitley [as finance minister], they are all doing the same thing.”

Beside auction money, operators pay 28-30 percent levy on their adjusted gross revenue, the highest anywhere in the world. The return on investment of Airtel, the largest operator, is close to four percent. “Forget about the second, third and fourth players,” says a telecom analyst with a Mumbai-based brokerage firm. Globally, operators have a return ratio of 15 to 18 percent – and that too with the cost of capital at four to five percent. In India it is the other way round. The cost of capital is eight to 10 percent and return ratio is four to five percent.

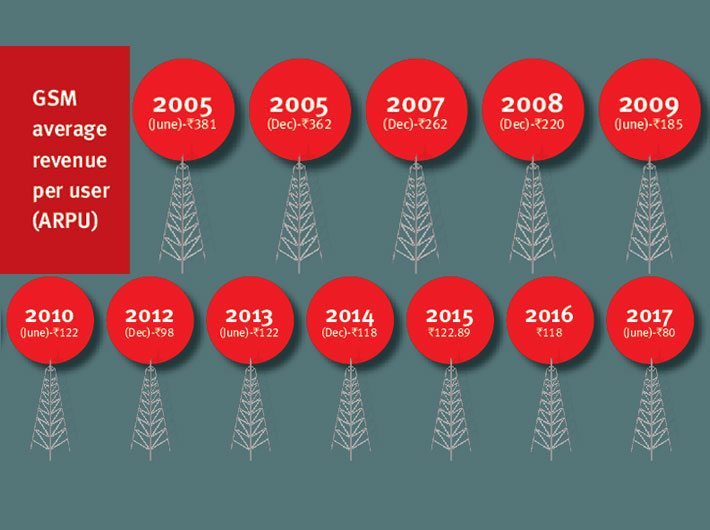

Moreover, the average revenue per user (ARPU), too, is the lowest in India. India is not about ‘scale’ as it is projected, the analyst argues. He compares the domestic market with that of the US and China. The India telecom market is $30 billion. The US market is $200 billion. Chinese state owned telco, China Mobile Communications Corporation, has a revenue of over $100 billion, which is more than India’s total spend on telecom. “If operators don’t make money, why would they invest? If they don’t invest, what is the quality of service that you get?” asks the analyst.

That remark must be seen in the light of what happened in after Reliance Jio offered voice for free and data at competitive pricing: All operators cumulatively registered a negative growth of 2 percent in their revenue for 2016-17. Their revenues have fallen quarter after quarter since June 2016 (see box). Evidently, this will cause loan repayment problems. The Reserve Bank of India has referred to telcos’ debt as stressed assets. “Any telco going belly up would mean creation of Rs 50,000 crore to Rs 60,000 crore NPA overnight, adding to the existing NPAs,” says the former TRAI official.

The genesis

The mobile services industry began as a duopoly. Before 1997, the department of telecom (DoT) was the policymaker, regulator, service provider and arbitrator, all in one. It was a time when there was no TRAI, Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL) or Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT). After the liberalisation of the Indian economy, the government realised it needed Rs 23,000 crore to increase basic telecom penetration. This led to the formulation of the first national telecom policy in 1994, which provided for setting up cellular networks in metro cities. With uncertainty of revenue, it was decided that only two players would be allowed to operate in a metro. The spectrum was bundled with the licence. The winners had to pay an annual licence fee to the DoT. For Delhi, Airtel and Sterling Cellular (later sold to the Ruias-owned Essar Cellular Delhi Service) were permitted as service providers. Right after the grant of metro licences, the government opened up state licences – what we now call the service licence areas (SLA). In subsequent years, however, a majority of the operators defaulted on their annual licence fee commitment, due to erroneous anticipation of revenue. That’s what prompted the National Telecom Policy 1999, changing the licensing regime to a fixed annual fee, a percentage of operators’ annual revenue.

On its part, the government wanted to introduce more competition in the sector and bring two additional players. “The industry was asked to give up duopoly to welcome two additional players. That’s how BSNL came up as the third player. Later, the CDMA operators came in,” says Rajan Mathews, director-general of the COAI. In those days none of the present-day companies existed. Today’s Idea started as Birla AT&T. When American firm AT&T exited, it became just Birla. Then Birla rebranded as Idea. Vodafone bought rights from Max Hutchinson (‘Hutch’). The Tatas came in later, tying up with Docomo. When Docomo exited, it became Tata Teleservices. Around 2001, the government decided to give licence to a fourth operator through a bidding process. An auction was held thereafter. None of the operators came forward for the auction. When the bids finally happened, the participants said that they were ready to pay (approximately Rs 1,056 crore) for licence if it was bundled with 4.4 Megahertz of spectrum.

This was the time when Reliance Communications made a backdoor entry in the market. Though it had a permit for a geographically limited technology called wireless in local loop (WLL), it went ahead and offered full mobility services, no different from the regular CDMA technology. Thus, compared to the competition, it got its licence for cheap, but offered nearly the same service. The company was taken to court, but a resolution was reached when it agreed to pay the licence fee it avoided for full mobility services. In 2003, the DoT introduced unified access service licence (UASL), allowing operators to offer fixed and mobile services under the same licence, using any technology. In the meantime, the DoT came up with subscriber linked spectrum allocation, wherein the operators were asked to show how many subscribers they were putting on and accordingly they would be allocated more. “Companies like Airtel started getting additional spectrum bands in each service licence area based on the number of subscribers. For some SLAs, it was as high as 8 Mhz,” says Mathew.

The crisis year

The sector was doing well till 2007-08 – the most notorious and infamous period in India’s telecom history. During Dayanidhi Maran’s tenure as minister for communications and IT, the government decided to issue more licences, claiming it wanted to increase competition. They decided to have seven to eight operators. That’s how five new licences were given to five new companies on a first-come-first -served basis. Then came A Raja. With his ‘come all’ policy, he started giving licences to friends and favourites indiscriminately, which together constituted the 2G spectrum scam. Raja’s first-come-first-served policy was in brazen violation of all rules and norms.

The story dates back to February 23, 2006, when then prime minister Manmohan Singh approved constitution of a group of ministers (GoM) to “look into issues relating to vacation of spectrum” as demand for spectrum grew. It included the ministers of defence, home affairs, finance, parliamentary affairs, information and broadcasting and communication and IT. The terms of reference of the GoM included suggesting a spectrum pricing policy and examining the possibility of creation of a spectrum relocation fund.

On August 28, 2007, the TRAI made recommendations on the same, which were later used by Raja to defy other existing norms and reservations from the prime minister’s office and allocate 2G spectrum on personal preferences. The TRAI said in its recommendations: “The present spectrum allocation criteria, pricing methodology and the management system suffer from a number of deficiencies and therefore the authority recommends that this whole issue is not to be dealt with in piecemeal but should be taken up as a long-term policy issue.”

Further, it said: “The authority in the context of 800, 900 and 1,800 MHz, is conscious of the legacy, i.e., prevailing practice and the overriding consideration of level playing field. Though the dual charge in present form does not reflect the present value of spectrum it needed to be continued for treating already specified bands for 2G services, i.e., 800, 900 and 1,800 MHz. It is in this background that the authority is not recommending the standard options pricing of spectrum. However, it has elsewhere in the recommendation made a strong case for adopting auction procedure in the allocation of all other spectrum bands except 800, 900 and 1,800 MHz.”

When the telecom commission, headed by the telecom secretary, deliberated on the regulator’s recommendations on October 10, 2007, the four non-permanent members – the secretaries of finance, department of industrial policy and promotion, department of information technology and planning commission – were not informed about the meeting, the supreme court ruling in the 2G case later noted.

“To say the least, the entire approach adopted by TRAI was lopsided and contrary to the decision taken by the council of ministers and its recommendations became a handle for the then minister of C&IT and the officers of the DoT who virtually gifted away the important national asset at throwaway prices by willfully ignoring the concerns raised from various quarters, including the prime minister, ministry of finance and also some of its own officers,” the court said. As a result, the SC struck down 122 2G licences. After the SC ruling, the sector turned gloomy for investors, says the former TRAI official. “If you had invested in telecom, you were screwed. Dubai’s Etisalat, Telenor, Birla and Tata...they all burnt their fingers,” he says. Although the Comptroller and Auditor General’s estimated figure of loss to the exchequer in the 2G scam is still disputed by many in the industry, the impact of issuing so many licences and expanding the sector to 14 operators continued to haunt the industry.

In 2010, the spectrum auctions happened in an aggressive fashion. The operators had paid Rs 67,718.95 crore to the government. In 2014, again the 2G spectrum prices went high. The government collected Rs 61,162.22 crore. The debt started piling up. “What started initially as a Rs 60,000 crore debt became Rs 3,25,000 crore,” says the former TRAI official.

The margin of EBITDA, or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation, was low in 2012 and in the two subsequent years. It started improving after 2014. “That’s why, you see, Idea and Airtel had a stranglehold over the market. The industry as a whole carried on with this huge debt burden,” the official says. In 2015, the government went for another auction. It earned over Rs 1 lakh crore in spectrum auctions. Idea was debt-free till the March 2015 auctions. Just after the auctions their debt rose to Rs 35,000 crore, he says. Then came the 2016 4G auctions. The government expected an earning of $84 billion. It earned only $9.8 billion (Rs 65,789 crore). The 700 Mhz band, for high-speed internet services with low operational cost, was left unsold. The 900 Mhz band remained unsold too. The auctions were called a failure.

In September 2016, Reliance Jio entered the market with predatory prices. “You went back to the time of 2008,” says the official. By the end of 2016, the debt rose to Rs 4.5 lakh crore. By March 2017, it was clear that assets were stressed. “Given the situation, where is the money required for investment in the network? With their major money going into the auctions, operators had only two choices: either service their debt or invest in networks,” says the official.

Powerplay

While the government was auctioning the 3G network spectrum band, globally the technology was making way for the fourth generation or 4G network. In developed markets, voice and data are bundled together and served on IP network. During the 2010 spectrum auctions, Infotel Broadband Services Private Limited, a small ISP, bought 4G spectrum by bidding Rs 12,847.77 crore (5,000 times its net worth). According to reports, within hours, the company was acquired by Reliance Industries Limited and renamed Reliance Jio Infocom. Because the 4G band was initially meant for only data, the spectrum usage charge was reduced from five percent to one percent. For 3G and 2G, the SUC charge was higher as the two could be used for both voice and data. Even globally the 2,300 Mhz band has been in use for data. “You could use voice, but only through voice over LTE (VOLTE) tech. But it was very untried, untested, and an extremely low quality voice experience,” says Mathews. “Even if you developed VOLTE, then you couldn’t use it. As the government had restricted it only for data.” That’s exactly why 4G band was sold at a lower premium than 3G. Obviously, Reliance Jio had had its plans. One option the company had was to convert the licence to allow voice over the 2,300 Mhz band.

In 2013, the DoT asked the TRAI for guidelines on unified licensing, taking away restrictions on the usage of the frequency bands. The department gave a choice to all service providers that they can migrate to unified licence. Reliance already had 4G band (2,300 band). It moved to unified licensing and paid Rs 1,056 crore for offering voice over the band. The amount it paid, however, was the same amount which was decided by the DoT way back in 2001 for allowing entry of the fourth operator. “We objected that Rs 1,056 crore is not the relevant price point. Taking into account inflation between 2001 and 2013, the figure would have been well above Rs 5,000 crore for that band of spectrum,” Mathews says. The DoT overruled.

“Since then Jio had been investing on perfecting the VOLTE technology. That took them another three years. In the meantime, the device ecosystem, which wasn’t there before, gradually picked up,” says Mathews. Eventually, Reliance Jio launched its services for a trial for four months on September 1, 2016, offering all services for free. The trial was extended for another three months thereafter. And then again for another three months. And so on.

“Under law, Reliance Jio has to go to the regulator for approval of its tariff. The operator can’t issue a tariff plan unless the TRAI has approved it. In this case, the TRAI didn’t disapprove, which is construed as approval,” says the former TRAI official. The other operators complained that TRAI was not applying its mind, and they went to TDSAT. The tribunal sent a communication to TRAI, asking the latter to take a decision. The regulator did nothing.

Between September 2016 and June 2017, it was a field day for Reliance Jio, the official says.

In June 2016, the sector’s gross revenue was Rs 73,334 crore. It fell to Rs 63,315 crore in March 2017 and remained Rs 64,889 crore by June 2017. Subsequently, their adjusted gross revenue fell from Rs 53,383 crore to Rs 40,381 crore (March 2017) to Rs 39,778 crore (June 2017). Naturally, the government revenues, which comes from levies on operators, fell. The average revenue per user for operators fell from Rs 118 in 2016 to Rs 80 by June 2017.

When things came to a head, the telecom commission, headed by telecom secretary JS Deepak, wrote to TRAI on February 23, 2017, conveying its concern over the free hand given to Reliance Jio in running the promotional offer for over 90 days and then subsequently continuing for another three months. It urged the regulator to discharge its duties in letter and spirit, as the government revenues were declining, and the adverse impact on the incumbents’ investment and repaying capacity. The Economic Times had reported that the free, promotional offers of Jio led to a revenue loss of Rs 685 crore to the government.

On Tuesday, February 28, Deepak left for Barcelona to attend the Mobile World Congress. On Wednesday, the government ordered his transfer as officer on special duty, designating him as India’s permanent representative to World Trade Organisation (WTO), with immediate effect from June 1. He was given a three-month paid leave. “If he had to be made the India representative at WTO, what was the need for taking charge from him three months in advance,” says the former TRAI official, indicating the orders came from the top – meaning, Mumbai, he clarified. And by 2015-16, companies which were making profits were now in huge debt, the former bureaucrat says.

Interconnection charges

Meanwhile, in 2016, the regulator had also floated a consultation paper to review the interconnection usage charges (IUC) – the amount paid by the calling party’s operator to the receiving party’s operator on per call basis. The last time it was revised was in 2015 when it was brought down from 20 paise to 14 paise, calculated using a model referred as ‘LRIC plus’ or ‘hybrid LRIC’, used world over by regulators to decide call termination charges.

The old players and the new entrant, Reliance Jio, were at loggerheads on interconnection charges. The old players demanded doubling of IUC, while the latter batted for a complete phase-out of interconnection charges and migration to a ‘bill and keep’ model, wherein the operators don’t charge each other for call termination.

After “wide consultation”, the TRAI issued an IUC amendment on September 19, slashing interconnection to six paise. The regulator used the pure LRIC model. The older players and several telecom experts, including former TRAI chairman Rahul Khullar, strongly criticised the move, asking the regulator to explain why it chose the pure LRIC model when globally, the hybrid LRIC method is used. “On IUC, it seems, the decision was already taken (to reduce it to six paise). The regulator justified it by taking whichever model that would help in calculating the lowest figure,” says another senior telecom expert. In the IUC ruling, the TRAI asked the operators to move to the IP network, which would reduce the cost of operation, and make termination charges redundant.

With time, certainly, there is need for operators to modernise their network. Yet they need to continue with the legacy network too. “At present, 50-60 percent of the subscribers still hold feature phones and will have to buy smartphones to be able to benefit from the IP network,” says the former TRAI official. The IUC cut will impact networks in rural areas, wherein the number of calls received is far greater than the number of calls made (outgoing calls). “It is like international calls, wherein maximum calls originate from abroad and less calls from India, because of the better paying capacity of those living abroad,” the former TRAI official says. Reacting to the ruling, Vodafone said that it may have to shut down some of its towers in rural areas.

Rural impact

If operators completely switch to 4G, what will happen to 60 percent subscribers, who still use 2G network? At present India has 200-225 million smartphones. “The remaining 400-500 million have feature phones. Where will the people go?” the official asks. “Subscribers in rural areas have limited purchasing power. Why would they shell out Rs 1,500 to Rs 2,500 when they are barely managing with a phone worth Rs 500? You can’t expect subscribers to act on whims and fancies of someone,” the analyst adds.

The drastic slashing of IUC, say telecom experts, will certainly have an adverse impact on subscribers in the northeast, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha – referred to as Circle C in the telecom jargon. It will adversely impact areas where market needs to be developed and networks need investment. Circle A and Circle B towns, where the market is huge, will not get impacted (see box). “These are established markets and operators have incentives to invest and hopefully provide service that people need. However, in areas where network is non-existent – and there are a large number of places like that – the competition in the market will not help,” says Mahesh Uppal, director, ComFirst – a telecom consultancy firm.

The extreme competition introduced by Reliance Jio and the subsequent IUC ruling will curtail whatever little bit of investment is going to the rural networks, say telecom experts. “I would think 1,00,000 villages across northeast, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha will be facing this problem,” Uppal says. Moreover, the chances of connecting the 50,000 unconnected and unserved villages look dim. The lack of investment for under-served areas becomes vicious. Because the demand is weak, operators don’t see a business case for setting up the network, and because they don’t develop network, the demand doesn’t go up.

Bold reforms

Apparently, India has the highest levy in the global telecom market. The countries going for spectrum auctions normally take minimal annual administrative fee of one to two percent. In India both the auctions and the spectrum usage charges coexist. Add to it six percent of licence fee, including five percent universal obligation fund and GST. “The USOF [universal service obligation fund] should be disbanded. If telcos have rolled out network in commercially viable rural areas why should they pay to the USOF?” asks the former TRAI official.

Currently they pay 28-30 percent of the revenue back to the government. “If you reduce those levies, the operators will get to keep more of the revenue that they make and will have the incentive to invest in places where currently they don’t,” says Uppal. The licence regime is at the core of the problem of this sector, he adds. On part of the government, the NTP 2012 clearly says that the government would rationalise the payout. It has not delivered on its commitment, notes the former TRAI official.

The second major area of reform is spectrum regulation. It doesn’t incentivise efficient use of spectrum or disincentivise inefficient usage. Here consumers and government both are at the receiving end. “If I have bought the spectrum and if I don’t generate revenues, I am using it inefficiently. There is no great incentive to use it efficiently,” says Uppal.

Eventually, it’s a zero-sum game. If there is x amount of capacity (bandwidth) and the subscribers are many, it will be divided several times, and that’s what we are experiencing.

One of the losers from Jio’s operation is the government itself because it is now figuring out that since the new operator is not making money as it doesn’t charge its consumer, there is no revenue that it gets and hence there would be no revenue share with the government, he says. To use spectrum more efficiently would mean getting more subscribers, providing better capacity and better bandwidth. “Currently you don’t have punishment for people who use spectrum inefficiently,” says Uppal. Reliance Jio offered services for free. It didn’t make revenues but it got more and more customers so it balanced out. But the government and competition lost out, say telecom experts.

Taking note of the poor financial health of the sector, the DoT formed an inter-ministerial group (IMG) in May to suggest corrective measures. The IMG, which included officials from the communications and finance ministries, had a limited mandate. Among its recommendations accepted by the telecom commission are allowing payment for auction over a period of 16 years as against the current 10-year duration and the lowering of interest rates on penalties imposed on operators. “These are like bandages, the industry requires a major surgery,” says the former TRAI official.

The telecom industry is now effectively a three-player market, an imposed oligopoly – which could be a problem for ensuring competition, believes Uppal. From a policy and regulatory angle there is need to ensure that competition would remain same and the quality of service is upheld. From a policy perspective, we need to ensure competition. One would not want to be in a situation where a set of operators hold subscribers to ransom, says Arpita Pal Agrawal of PwC India. “There should be consideration of investable funds with operators with the right checks and balances. One of the option is that the government could consider reducing revenue share to cover its administrative costs as operators have already paid for spectrum at market prices. If the government believes that the sector is truly an enabler then should revenue generation be a key consideration for deciding policy interventions?” says Agrawal.

In India regulators are personality driven, says the industry veteran quoted earlier in the story. There is no consistency and uniformity in regulations. Oligopoly is not a bad thing as long as the regulator is able to maintain the competition, the industry veteran says. Moreover, telecom is a highly capital intensive business. “If you don’t have the surplus you will not invest, especially if you are not seen as good debt for the banks. They won’t lend you money, and you won’t have surplus yourself,” says Uppal. “If you invest less, clearly the consumers will be impacted.”

pratap@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the November 15, 2017 issue)

As many as 1,351 candidates from 12 states /UTs are contesting elections in Phase 3 of Lok Sabha Elections 2024. The number includes eight contesting candidates for the adjourned poll in 29-Betul (ST) PC of Madhya Pradesh. Additionally, one candidate from Surat PC in Gujarat has been elected unopp

The provisional figures of direct tax collections for the financial year 2023-24 show that net collections are at Rs. 19.58 lakh crore, 17.70% more than Rs. 16.64 lakh crore in 2022-23. The Budget Estimates (BE) for Direct Tax revenue in the Union Budget for FY 2023-24 were fixed at Rs. 18.

The much-awaited General Elections of 2024, billed as the world’s biggest festival of democracy, began on Friday with Phase 1 of polling in 102 Parliamentary Constituencies (the highest among all seven phases) in 21 States/ UTs and 92 Assembly Constituencies in the State Assembly Elections in Arunach

Fit In, Stand Out, Walk: Stories from a Pushed Away Hill By Shailini Sheth Amin Notion Press, Rs 399

The recent European Union (EU) policy on artificial intelligence (AI) will be a game-changer and likely to become the de-facto standard not only for the conduct of businesses but also for the way consumers think about AI tools. Governments across the globe have been grappling with the rapid rise of AI tool

The Indian Railways is celebrating 171 glorious years of its existence. Going back in time, the first train in India (and Asia) ran between Mumbai and Thane on April 16, 1853. It was flagged off from Boribunder (where CSMT stands today). As the years passed, the Great Indian Peninsula Railway which ran the