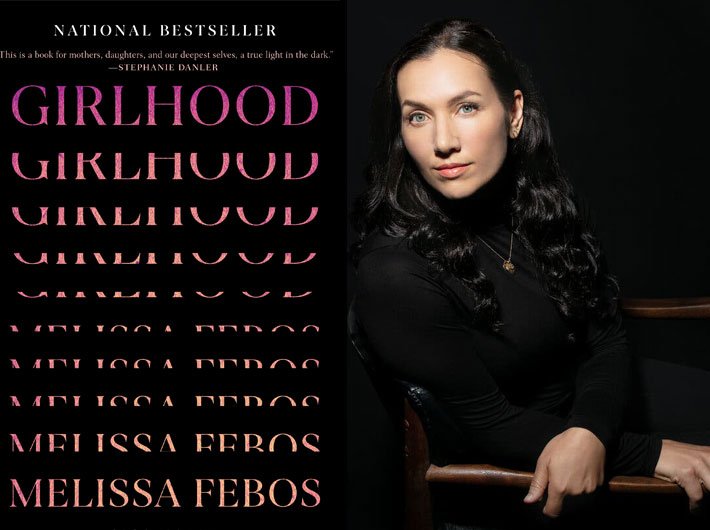

Melissa Febos’s new collection offers gripping stories about the forces that shape girls and the adults they become

GIRLHOOD

By Melissa Febos

Bloomsbury / 336 pages

Melissa Febos wowed readers and critics with her ‘Whip Smart: A Memoir’ (2010). It was followed up by another collection, ‘Abandon Me: Memoirs’ (2017). This year, with ‘Girlhood’, she has now turned her preference for personal essays and memoirs to explore what it means to grow up as girls and come to terms with the body.

Febos, an associate professor at the University of Iowa, where she teaches in the Nonfiction Writing Program, “examines the narratives women are told about what it means to be female and what it takes to free oneself from them.”

Written with her characteristic precision, lyricism, and insight, ‘Girlhood’ is a philosophical treatise, an anthem for women, and a searing study of the transitions into and away from girlhood, toward a chosen self.

Here is an excerpt from what the New York Times Book Review described as “the feminist testament to survival”:

L E S C A L A N Q U E S

I HAVE SEEN PICTURES of Cassis, and so am unsurprised though still seduced by its beauty—the narrow winding roads and stucco buildings that lead downward, the shocking turquoise blue of the bay, or the castle-topped cliffs that rise around the nestled port town. No one has told me about the cicadas, though. When my taxi from Marseille stops at my destination and I open the door, I startle at their song. It surges from the trees, blankets everything in its pulsing whir. It sounds machinelike, though I know it is thousands of giant insects, their bodies heaving with desire.

I have come to Cassis for a month, along with ten other artists. I will live alone in a small apartment on the top floor of a building whose tall windows overlook the bay with its green-eyed lighthouse (Fitzgerald finished ‘The Great Gatsby’ not far from here, and it is rumored that its green light was inspired by this one), the cliff of Cap Canaille that changes color with the position of the sun, the town beach crowded with bodies, and the relentless blue Mediterranean that stretches to the horizon where it meets the relentless blue sky.

Every morning I pull open the windows and bathe in the early-morning breeze off the water. I have recently suffered a back spasm whose symptoms cascaded down my body in a manner so painful no medicine could assuage it. While no longer in pain, I have learned something of my body’s fragility. At thirty-seven years old, I do not expect it to reverse.

When all of the windows are open, I eat a perfectly ripe peach over the porcelain sink in the tiny kitchen, its juice streaming down my forearm. Then I perform a series of gentle stretches that were not possible eight weeks ago. By the time I finish, the cicadas have risen with the sun, its heat engorging their abdominal membranes enough to produce that sound. I meditate for twenty minutes. My eyes closed, I imagine their thrumming as a ring of light that surrounds the building, each insect body a bright ember.

The call of a male cicada can be heard by a female a mile away, and some are so loud they would cause hearing loss in humans were the insect to sing close enough to the ear. Cicada nymphs drop from the trees in which they hatch and burrow into the ground, often eight feet below the surface. The cicadas in southern France spend almost four years underground, though a brood rises every summer to sing and screw for a few months before they die. All of the souvenir shops in Cassis sell porcelain cicadas, wooden cicadas, tea towels with cicadas

printed on them. North American species of cicadas, those of my own childhood, have longer life cycles and often spend seventeen years underground before tunneling their way to the sunlight and climbing out of their old bodies.

It has been seventeen years since my last visit to France, a trip I haven’t thought about in a long time, but whose details start returning to me the way the language does. Words emerge from my mouth at the market that I didn’t know were buried there—seulement, les fenêtres, désolée— jostled loose by the voices around me, risen from wherever they have been sleeping for nearly two decades.

IN THE SUMMER OF 2001, before my final semester of college, I got a job at the New Press, an independent leftist publisher whose list included works by Noam Chomsky, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Simone de Beauvoir. My job was to sit in the air-conditioned Manhattan loft and, among other light administrative tasks, respond to the novelists who often mailed us their entire printed manuscripts for consideration. “Dear Author,” I would type. “The New Press rarely publishes novels and never those by American authors.” This fact was immediately obvious if one simply glanced at our catalog. Still, myself an aspiring novelist, I pitied them as I dropped their manuscripts into the recycling bin with a funereal thunk. Most mornings I wandered through the cavernous store-room with its twelve-foot industrial shelves of books and selected one or two to read that day at my desk. If I liked a book especially, I brought it home in my purse. I still have my stolen copy of Studs Terkel’s Working. It would have been a great job for the person I would have been if I had not been addicted to heroin.

I was only twenty, but already beyond the charmed phase of believing I could outsmart the drug. I had begun trying to stop and still thought I might be able to do so without help. […]

[Excerpt reproduced with permission of the publishers.]