[This article was published in the October 1-15, 2013 edition, when LK Advani was of course in a different sort of predicament.]

I will begin with a disclaimer. Any narrative about the rise and fall of a political personality will contain subjective assessments, prejudices and maybe even some preconceived notions. This attempt to delineate the political journey of a leader of LK Advani’s stature, who virtually dictated the country’s political agenda for 15 years from 1989, is unlikely to be an exception.

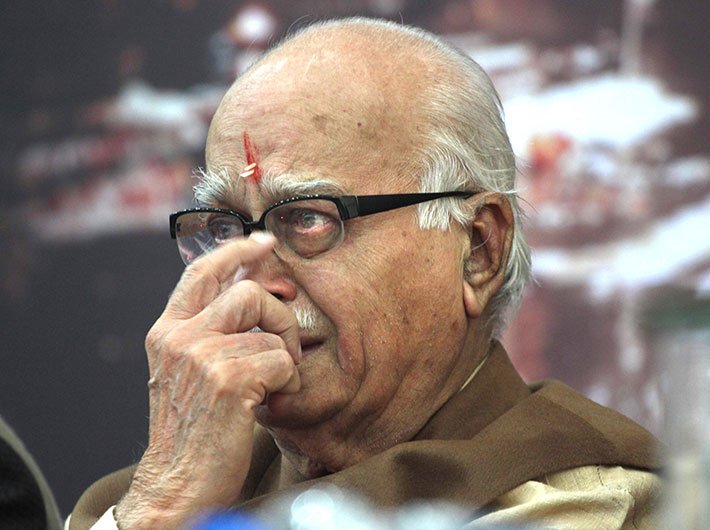

Advani’s fortunes have been on the decline for a long time now, slowly but steadily eroding his stature as a political and ideological colossus within and outside the saffron brotherhood. But he has never been in a place where he might have been staring at splendid isolation from his political progeny. His influence may have been on the wane, but his stature, especially in the public sphere, was intact. Just a few years ago, it would have been silly to imagine that Advani would ever fall from grace or that he would take the precipitous tumble towards total irrelevance. That has now happened.

Advani built the BJP and his career on his farsightedness, astuteness and a dogged pursuit of Hindutva. Today that doggedness is seen as burden, as a severe case of myopia with no hope of healing. His fight for relevance evokes more ridicule than admiration even within the brotherhood. Those who owe their political careers to him laugh at his isolation and describe it as a “well-deserved fate”. One of his aides went as far as to remark that “the reality is that today the party cadre does not even want to see his picture on posters, but he does not see this reality”. His open opposition to the coronation of Narendra Modi, the new star of the Sangh brotherhood, has evoked derision and ridicule in the party and in the public. The exasperation is palpable: Doesn’t he see the writing on the wall? Can’t he see that his time at the top is over? Why doesn’t he go in grace?

To judge, rather condemn, the grand old man of the Hindutva family exclusively in the context of his immediate political grandstanding – as a stubborn roadblock in Modi’s path and his refusal to fade away into oblivion despite a determined push by his political off-springs – will be to do injustice to his enormous political legacy nurtured over five decades of a sterling career. So a deep dive into Advani’s long innings and his contribution to shaping the BJP and the nation’s politics is called for.

It is impossible to conceive that in the matter of a just a decade, a person once described as an excellent organiser and the epitome of political shrewdness and the lifeblood of the BJP could mutate into a self-seeking and scheming persona with little to contribute for the party. Another political stalwart had once warned Advani that the RSS would not blink even once to pluck him out and cast him aside. This was in 1977. Chaudhary Charan Singh was the home minister in Morarji Desai’s Janata Party government. He was unhappy about many things but his principal grouse was the dominance of the upper castes in Morarji’s government. He was constantly taking pot-shots at Morarji and his son Kanti Desai. Advani was concerned that this constant clanging between the prime minister and his number two man could put the first non-Congress government of the country at risk (that ultimately happened) and tried to dissuade Charan Singh from raising a banner of revolt on caste lines. Charan Singh brushed him off with a stinging retort: “Aap Sindhi ho Advani. Aap jaatiwad nahi samjhoge. Vajpayee Brahmin hain. Iss liye RSS unko kabhi chhoo bhi nahi sakti lekin aapko ek jhatke mein kinaraa kar degi (You are a Sindhi so you will not understand the full significance of caste dynamics of India. Vajpayee is a Brahmin, so

the RSS will never be able to hurt him but it can cast you aside in the blink of an eye).”

How prescient! But Advani, then just 50, paid no particular attention to this great insight from the tallest leader of the backward castes perhaps taking it as the rant of an old man out of depth with the reality of his time (just what many think of Advani now). Advani had already spent as many decades as Vajpayee partaking of the same ideological fountainhead (RSS) which preached religion (Hindutva) as a grand identity subsuming all caste identities. So, to think that such an organisation would discriminate on caste lines was unthinkable for him. He did not realise the political wisdom of Charan Singh.

During the Janata Party regime, Morarji was extremely fond of Advani. As an English-speaking Jana Sangh leader, Advani came across as quite liberal in his outlook and exceptionally straightforward in his conduct. Desai regarded him as a dedicated performer as I&B minister and a leader with great potential. Advani was considered an amiable, non-confrontationist and suave leader even by his rivals.

But this genteel façade concealed a tough bargainer. This became evident when the Janata Party experiment failed. Chandra Shekhar tried to foist Madhu Limaye as the president of the rump of the Janata Party of which the erstwhile Jana Sangh was a part. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Advani’s senior, acquiesced but Advani resisted strongly. “You are not making Vajpayee the president simply because he belongs to the Jana Sangh,” Advani told the veteran socialist without sounding hostile. That meeting at Advani’s Pandara Park residence sowed the seeds of a new political party, the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party). “We are being treated like untouchables,” he told Vajpayee and proposed floating the BJP as a new party that would do politics on its terms and make its place under the sun. Vajpayee agreed.

There are many anecdotal accounts to prove that the BJP’s inception and its onward journey were full of hiccups. Vajpayee agreed to don the role of the party president after several leaders refused to take up the assignment. Bhai Mahavir and Vijaya Raje Scindia, for example, flatly refused to take up the job. The choice ultimately fell on the Vajpayee-Advani duo. Between them, they shouldered the responsibility of leading the party, negotiating one crisis after another. On its debut, the BJP won 13 seats in the 1980 general elections. But in the 1984 elections on the back of Indira Gandhi’s assassination, it was reduced to two seats in the Lok Sabha. From this point, the BJP could have gone the way of scores of other parties before it, downhill and straight into dustbin of history. But it did not. The party stumbled upon the idea of the Ram Janmabhoomi campaign.

Advani was quick to understand the simmering social discontent and warned Rajiv Gandhi when the latter called on him after the Shah Bano episode. (Rajiv had gone to Advani’s place to condole the death of the veteran leader’s father.) “You are walking into a trap,” he cautioned the youthful PM who chose to ignore the advice. (Shah Bano a Muslim divorcee was granted alimony by the apex court. The Muslim clergy rose up in arms contending that this was against the Sharia. Rajiv Gandhi’s government brought in a regressive law to nullify the ruling.) He found an opportune moment when VP Singh’s rebellion over the Bofors payoff kicked off an impromptu anti-corruption movement across the country. Advani asked the BJP cadre to join the mass movement. As a young party of around ten years, the BJP cadre then had no experience of a mass movement and Advani shrewdly piggybacked on V P Singh’s charisma to give his inexperienced party cadre the taste of a national political movement. This experience would come in handy for the BJP in the early 90s during the Ram Janmabhoomi movement.

In 1989, when V P Singh was getting ready to fight the elections against the Congress with the BJP’s support, Advani again demonstrated his skills as a hard bargainer. He extracted a large share of seats for the BJP telling V P Singh that “if I were to withdraw, my party’s cadre would be happy but you would lose the chance of becoming the PM”. This argument clinched the deal between Singh’s Janata Dal and the BJP. It was a different matter that this deal was honoured more in breach than in practice.

That was an alliance of two divergent ideologies, so how did Singh fall for the trap? Singh did not mind any prop that would help oust the Rajiv government. He was cocksure of marginalising the BJP once the government was formed. Singh’s assessment was premised on the assumption that forces that coalesced to form the Janata Dal would remain intact. “I was sure that I would bring the BJP down to its original position (or two seats in the Lok Sabha). If the Janata Dal had not split, I would have accomplished that,” Singh once told this correspondent when asked if he held himself responsible for the ascendance of the Hindutva forces.

But Singh admired Advani’s skills as a politician. “The problem with him is that he flouts the rules of the game and puts a goal from outside the D,” he would say in football analogy. But, he told this correspondent, he had warned Advani that he would ultimately end up the loser for launching a movement on the shoulders of sadhus of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad. “Maine Advani ji ko kaha thha ki yeh sadhu apne maa baap ke nahi hote hai toh aap ke kaise honge? (These sadhus have dumped even their parents, how can you depend on them?).” Singh revealed this in 1999, when the VHP was trying to rake up the mandir issue even as Vajpayee-Advani’s NDA was trying to avoid it.

Advani’s strident rath yatra gave many a sleepless nights to prime minister V P Singh. Advani launched his yatra from Somnath much against the wishes of Vajpayee. Vajpayee believed that a leader riding on a motorised chariot was the kind of drama which might suit NT Ramarao, given his background as a film star, but not a mainstream politician. That is why Vajpayee never boarded the Toyota chariot though he agreed to join it and flag it off on certain occasions.

Advani drew strength from his perceived resonance with the RSS ideology at a time when the chasm between Vajpayee’s moderation and the Sangh Parivar’s militant Hindutva was widening. Advani was the Sangh’s favourite while Vajpayee was considered a barely tolerable leader – tolerated thanks only to his stature, oratory and his Brahmin identity. Despite being at odds with Vajpayee many times, the RSS hardliners could not muster enough courage to marginalise him beyond a point though there were occasions when he was pushed around more than a little bit.

BJP’s former ideologue KN Govindacharya is a key witness to the power struggle aimed at upstaging Vajpayee in the 1990s. After the 1991 elections, the BJP emerged as the main opposition party and was thus entitled to the post of leader of the opposition. Bhaurao Deoras, the joint general secretary of the RSS, sent for Govindacharya and conveyed to him an unambiguous message that the post should go to Advani. Govindacharya recalls that Advani initially hesitated but finally accepted the RSS’s command. Vajpayee was relegated to number two for the first time. It was only after the Babri mosque demolition that the RSS, in need of a moderate face, allowed Vajpayee’s reinstatement as numero uno.

Govindacharya denies the charge that Advani is a self-seeking politician. But at the same time he argues that he is essentially a power-seeking politician for whom the ends justify the means. He would use any and all means to attain power even if it meant undermining the core ideology of the sangh. The reference here is to Advani’s fondness for Pramod Mahajan, the biggest fundraiser for the party. Mahajan’s indiscretions and his dubious role as a wheeler-dealer were never a concern for the BJP patriarch so long as he operated without their having to get involved directly. Mahajan was pretty open about it. “I don’t raise money for myself. I do it for the party. Let my leaders say that the party does not need the money, I will stop collecting,” Mahajan once told this correspondent in his trademark candour bordering on arrogance.

Through all this, though, Advani always gave new life and direction to the BJP and ensured it stayed on course to becoming the only real challenger to the stranglehold of the Congress party at the centre. In the 1990s, it was Advani who introduced “pragmatism” as a new idiom in the party’s political culture. After the Babri mosque demolition the BJP quickly became a political pariah. Party after political party drifted away from its “communal” politics. To rub salt on its wounds, in the elections that followed soon after, the BJP was routed in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh. Advani quickly understood the risk of isolation and political ‘untouchability’. In the following years he went out of the way to court allies insisting that ideology should not come in the way of forging political alliances. Soon he won over unlikely allies in George Fernandes and Nitish Kumar. “Ideology has nothing to do with governance,” was his new formulation. It did not go down well at all with the RSS hardliners because, as Govindacharya suggested above, it was seen as ends justifying the means. Given Advani’s centrality to the BJP’s scheme of things and his national eminence, he carried the day. By the time the BJP went into elections in 1999 Advani had managed to tie up pre-poll alliances with a galaxy of 20-odd parties straddling the entire the political spectrum. This included Chandrababu Naidu’s TDP, Mamata Banerjee’s TMC and even Farooq Abdullah’s National Conference.

This meant a complete burial of the Mandir agenda and so another debit entry was made on his score sheet by the RSS. Having begun the short BJP reign with a trust deficit, Advani started to lose his ground within the Sangh Parivar during the six years of the NDA regime. Along with Vajpayee, he was also seen as a leader not amenable to the Sangh Parivar’s vision of governance and politics. A major confrontation came up when as home minister Advani could not ensure the safe release of four RSS workers who were abducted by insurgent groups in the northeast. His tepid response to the RSS entreaties for “effective intervention” fell on deaf ears and the captives were murdered. Advani fell a few more notches in the eyes of the RSS.

This period also coincided with serious differences cropping up between Vajpayee and Advani over certain issues of functioning. The most prominent among them was the dual job profile of Vajpayee’s aide Brajesh Mishra, as the national security adviser and principal secretary to the PMO. Given Mishra’s family background (son of DP Mishra, veteran Congress leader and once the chief minister of Madhya Pradesh), the RSS had serious reservations about him. Advani raised the issue with Vajpayee who refused to be dictated on the choice of his aide. The RSS again felt let down by the man on whom they relied the most. Advani contended that it would be difficult to run a coalition government if such differences were stretched beyond limits. This led to further devaluation of his currency with the RSS. But because he had nurtured the second-generation leadership of the BJP, his overweening influence on the party structure was still intact. But this shield of invincibility would last only as it was powered by, well, power.

The real troubles for Advani began in 2004 when the NDA lost power. Advani chose to become the leader of the opposition while Vajpayee was made chairman of the NDA parliamentary party. This demonstrable streak of ambition became more pronounced when he took over as party president in 2005 from a weakling M Venkaiah Naidu, a rootless leader from Andhra Pradesh who owed his pre-eminence in the party to his proximity to Advani. A chagrined RSS leadership had been seething in silence over these deft manoeuvres by Advani who had done all this without taking RSS on board. For the first time, the RSS-VHP combine was seen as openly ranged against him. The VHP boycotted Advani during a meeting of its stalwarts at Haridwar in 2005.

This ongoing tussle had its impact within the BJP as a section of the RSS pracharaks loaned to the BJP started fuelling resentment over the veteran leader’s style of functioning. His unilateralism came in for much criticism and his reliance on his own family was much frowned upon. In this atmosphere of growing distrust and hostility, Advani’s visit to Pakistan and his comments on Mohammad Ali Jinnah turned out to be the last straw on the RSS’ back. To give a “secular” certificate to the originator of the two-nation theory was to pollute the ideological bloodstream of the RSS. He was deserted by even his understudies who by now started seeing their growth in Advani’s decline.

Advani was taken aback by this aggressive stance of the RSS and the reaction of his supporters. In his attempt to retain his position of pre-eminence he alternatively vacillated, hit back and struck conciliatory postures. But it all only added up to undermining his moral authority within the Sangh Parivar. For the first time in his career he was on the defensive, unsure and contradicting himself. At times he found himself ranged against successive BJP presidents like Rajnath Singh and Nitin Gadkari. He loathed their tendency to rush to Nagpur to solve party crises and the undue interest the RSS was taking in the day-to-day functioning of its political arm. But he himself became a regular Nagpur pilgrim. For most of the history of the BJP, if he was seen as pushing Vajpayee into the forefront in selfless service of the party, now his actions were being seen as machinations to arrogate power to himself resulting in a crisis of credibility. This impression was cemented when, after losing the 2009 election and under pressure from the RSS to make way for young blood, he gave up the position of the leader of opposition to Sushma Swaraj but created a new position of chairman of the parliamentary board for himself.

Does this mean the end of Advani’s era in the saffron brotherhood? This piece is not meant as a political obituary of Advani but to shed some light on the conduct of a leader whose influence in shaping India’s politics has been significant. So that question will have to go unanswered for some more time. But, yes, Advani has lost the clout and wherewithal to match the energy and ruthless ambition of the new generation of the BJP’s leadership symbolised by Narendra Modi. However, it would be naive to believe that the veteran has lost his strategic acumen. Advani is neither a pushover like Mauli Chandra Sharma and Balraj Madhok (his Jana Sangh predecessors) nor is he Atal Bihari Vajpayee who could retain his pre-eminence even after many face-offs with the RSS. Advani will spend the rest of his political life in the space between past greatness and present diminution. And while waiting there for an unlikely return to relevance, the wisdom of Chaudhary Charan Singh’s advice must be ringing in his ears reminding him about his inability to comprehend the deeper dynamics of Indian politics. To the high priest of political Hindutva as an overarching political identity that must be both humbling and ironical.