Name: Unknown, Age: 40-45 yrs, Height: 5’5”

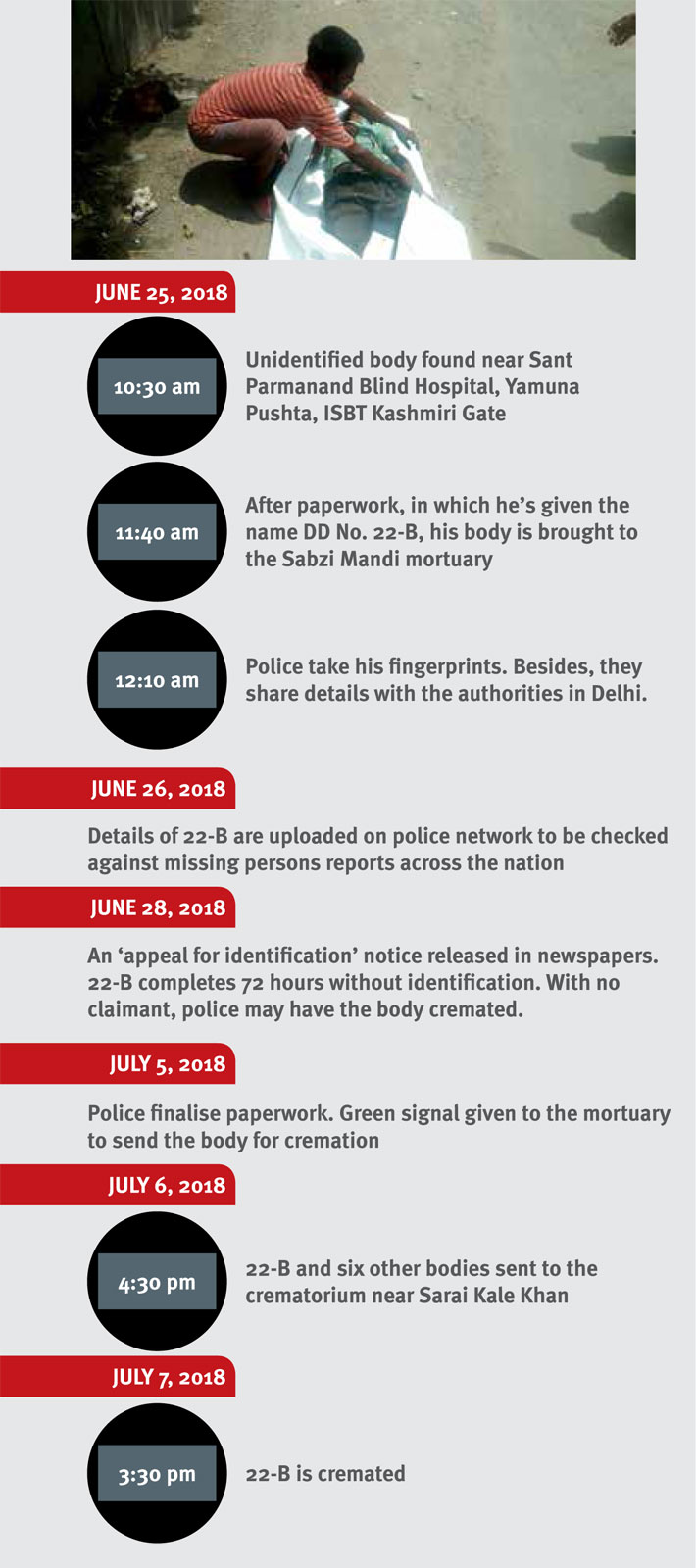

When they found him, no one knew his name. He couldn’t have told them, for he was dead. His body was found on June 25, when the temperature had gone beyond 40 degrees C even before noon, lying on a footpath in a narrow alleyway. It’s a cul-de-sac, ending in a narrow path leading to the Yamuna. Nearby stands the abandoned building of the Parmanand Blind Relief Hospital, which the authorities have sealed for encroachment on the floodplains. A little away is the Kashmiri Gate inter-state bus

terminus. Rickshaw-pullers, rag-pickers, poor migrant labourers wander in and out occasionally, but it’s otherwise desolate. Sometimes, constables walk by.

He was found by head constable Devendra and constable Narendra of Kashmiri Gate police station, one of 19 unindentified bodies found across Delhi that day. A dirty green shirt, grey trousers, a copper ring on his left hand, a pair of keys – that was all he had on him. After making sure he was dead, they informed their superior, sub-inspector Satish Kumar. The sub-inspector made an entry in the station’s daily diary (DD): 22-B. That would be the name he would go by in official papers. DD No. 22-B. In short, 22-B.

As a couple of layabouts helped the police lift his body into a van that would take 22-B to the mortuary, someone remarked, “Those keys found on him – they won’t be opening any locks anymore.”

For police stations in northern Delhi, it’s a common occurence. “The maximum number of vagabonds and migrant labourers with no homes are found in this part of Delhi,” says Satish Kumar. “Since there is no injury or other mark on the body, he probably died from overdosing on street drugs or from the heat.”

Constable Narendra, who has been patrolling the Kashmiri Gate area for a year now, says it is usual to find one unidentified body daily. During peak summer, it can go up to five or six in a day.

Police do not even write out a first information report (FIR) in such cases unless the body bears injuries or they suspect violence. Investigations happen only if there’s the remotest chance that the person might be from an achha ghar, or “good house”. In practice, that translates into someone from a middle or upper middle class home. So no FIR for 22-B. He will remain a DD entry.

“I will remain in charge of the body till it is cremated,” says Satish Kumar. “Generally, that takes about a week.”

So 22-B is sent to the mortuary, a low, white, single-storeyed building set in a semi-circular compound, it stands behind a wide, rusty gate. There is also a cluster of small structures, rooms for paperwork, two rooms for doctors, a waiting room. The gate opens only for vans bringing in the dead. It’s just a short walk from Metro Pillar No. 71 of the Red Line, between the Pul Bangash and Tiz Hazari metro stations. They call it the Sabzi Mandi mortuary, but there is no vegetable market in sight. Behind the building lies the forested area of Delhi’s Northern Ridge.

This is where 22-B will remain for now, till it is time to cremate him.

Inside, there is a pungent smell of chemicals and a stench hanging like a miasma. The waiting room is where families of people who have died in accidents, crimes or by suicide mill around. No one really seems to care. They go from the office room to the morgue and talk with the policemen. Quite often, they have to wait for more than eight hours, sometimes days.

Of bodies like that of 22-B, a worker at the mortuary says, “Most of the time, the authorities hand us decomposed bodies. Sometimes, parts are gnawed or eaten away by birds, rats, or other animals. The very sight is depressing. It’s impossible to even look at these bodies. Even policemen don’t want to be posted here. Given a choice, we would avoid this work, but we have to do our job.”

Meanwhile, Satish Kumar has circulated a photograph of 22-B on a WhatsApp group of the police department. He has also sent it to the Delhi state government, the police headquarters, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).

He has also had 22-B’s fingerprints matched against the records. “They don’t match any of our criminal records,” he says. The police have also decided that 22-B – probably because he’s uncircumcised – is a Hindu.

The next day, the sketchy details of 22-B are uploaded to the zonal integrated police site. At least from the paperwork, it is clear that the police have tried to reach all police stations across the country. There is no answer from anywhere. No matches with missing person reports at any police station. So 22-B will remain 22-B.

On June 28, the police put out a notice for 22-B in a newspaper, along with his mugshot. It was a bit vague and got the colour of the clothes wrong. It said:

Appeal for identification

General public is hereby informed that an unknown dead body was found near DDA Park near Sant Parmanand Blind Hospital, Yamuna Pushta, Delhi Dated 25-06-2018. In this regard a DD No - 22B dated 25-06-2018 has been lodged at P.S. Kashmiri Gate, Delhi.

The description of the dead body is given under:

Name: Unknown S/O: Unknown, R/O: Unknown, Sex: Male Age: 40-45 years, Height: 5’5’’ Complexion: Shallow (sic) Wearing: Sky blue shirt and dark blue pants, barefooted.

Sincere efforts have been made by local police to trace out the dead person but no clue has come to light so far. If anyone having any information about this dead person, please inform undersigned.

SHO, Kashmiri Gate

Meanwhile, 22-B lay on a gurney inside a cold room at the mortuary, wrapped in a white sheet. Since the police decided he did not die a violent death, there would be no post mortem.

Bodies are required to be kept for 72 hours before burial or cremation. But often, to save themselves frequent visits to the crematorium, the police wait till there are four or five bodies. In 22-B’s case, it took 12 days.

On July 6, around 4:30 pm, with no claim being made yet, 22-B’s body and six other bodies were taken to a crematorium run by the South Delhi municipal corporation near Sarai Kale Khan. There is no road leading to it. It is out of sight from the traffic-heavy Mahatma Gandhi Ring Road and the bustle of the bus terminus, on the Yamuna side. Hardly anyone knows of it. A mud path near the CNG pump on the eastern side of the main road takes you to a wooded area where some construction work is on. In an open area with a blue Shiva idol, there are two sheds for local villagers to cremate their dead. But the gatekeeper says locals hardly ever come there because it’s difficult to get wood, flowers and puja items here.

There is also a larger, structure of grey stone for those who die alone and unknown on the streets. In a cavernous hall with glass panes near the ceiling that are browned by soot and dirt stand two incinerators. The tiled walls too are dirty with soot. There is an air of grey and sombre dullness.

On the evening of July 6, an open white mini-truck with the legend ‘Guru ki langar seva’ brings in seven bodies, including that of 22-B. The bodies are all shrouded in white, bound with cord. Already, there are six bodies waiting there. “The eighth one among the 13 in the hall is of 22-B. It’s written on the rope binding it.” But all of them look alike, bound in death and anonymity.

An employee at the crematorium says the seven bodies that have been brought there that day will have to wait. Only one of two incinerators is working, and it takes two hours for a body to become ashes.

So the next day, July 7, a hot and humid Saturday, 22-B’s body is sent into the incinerator. No pyre, no flowers, no priest. He leaves alone. A worker murmurs, “May his soul rest in peace.”

So the next day, July 7, a hot and humid Saturday, 22-B’s body is sent into the incinerator. No pyre, no flowers, no priest. He leaves alone. A worker murmurs, “May his soul rest in peace.”

For sub-inspector Satish Kumar, there is still more paperwork to complete. “It could take nine months to a year,” he says. “We wait for a few months for missing person reports etc. After six months, we will send the papers to the sub-divisional magistrate’s office. Once the SDM signs the papers, the matter is considered disposed of.”

So one last time, 22-B will be remembered again. Albeit by policemen and officials to whom he was nothing more than DD No. 22-B.

deexa@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the August 15, 2018 issue)