AAP’s latest troubles – like its earlier success – underline the fact that people want principled politics

Sceptics are writing the obituary of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). First came the debacle in the Goa and Punjab assembly elections, then the rout on the home ground, in the Delhi civic elections. Soon the party’s internal disputes became public. The speculation, not without reason, is that AAP will soon die a natural death.

It may however be important to look at the AAP’s electoral performance in detail. In Punjab and Goa, it managed to secure 24% and 6% vote share, respectively, against two well-established parties. At a time when the non-BJP national parties are finding it difficult to hold their own in the face of a Modi wave, AAP’s performance was not bad. It is not unusual for a new entrant to face electoral defeat after a grand victory. If at all, the failure indicates the unreasonable expectations from the party.

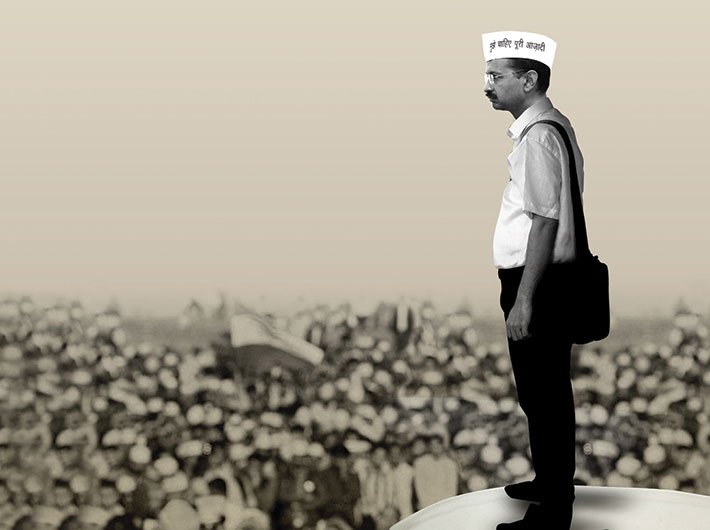

Such expectations from the AAP were largely because of its unusual origin. AAP originated out of a movement. Not just that, AAP originated out of a movement that demanded alternative politics based on principles and probity in public life. It was symbolic of a desire to change the existing nature of politics that was perceived as corrupt, opportunistic and based on bargains and compromises.

The rise of AAP must also be seen in the context of the desire of the ‘middle class’ (which was its core support base) to achieve economic well-being, growth and political power. A look into the socioeconomic context of AAP becomes instructive here.

With increased per capita income and declining poverty rates, India has seen a burgeoning middle class. According to a report by global consulting firm McKinsey, the Indian middle class stood at 250 million in 2007. National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) identified a class of aspirers immediately below this middle class, whose population increased by 12 percentage points in the past decade to 33.9 percent of the total populace. The census too shows the rise of a new class of consumers with ‘neo middle class’ characteristics that has expanded rapidly in the previous decade, adding 10-20 percent of the country’s population to its folds. The middle class is not just an economic category; it is also a social category. Despite the heterogeneity of the middle class, the expansion in its size had political consequences, in terms of its political aspirations.

The desire of the middle class to influence the political process was evident almost since 2012, when the country witnessed a series of civil society movements, especially the India Against Corruption movement and protests after the Delhi gang-rape, which elicited widespread participation not just in urban centres but also in semi-urban centres. The AAP provided the middle class with a vision of alternative politics and a platform to practise it. While the contours of this vision and its ideological moorings were not firmly established and there were pulls from different directions, the AAP demonstrated that there were alternative strategies of mobilisation and alternative ways of doing politics. It is this vision that won AAP the Delhi elections in 2014 and 2015.

Unlike many other regional political parties, AAP was not a splinter group, nor was it born out of dissensions within the existing parties. In that sense, AAP was not a chip of the old block. Its leadership was not made up of ‘career politicians’ in the strictest sense. Hence, AAP was perceived as a political formation created by a motley group of well-intentioned middle class intelligentsia that wanted to reclaim the lost ground of principled politics. Hidden in it was also a desire among the middle class to reassert its leadership in the political process. For a while, the party managed to capture the imagination of people across the caste-class and gender divide.

Where the AAP erred was to fall into the trap of aiming for continued electoral success at all levels and in all the states, without giving due consideration to the fact that success of a political formation depends on creating an organisational structure and a team of committed local level leaders. This is a time taking and painful process. It is difficult to sustain the momentum and morale of party workers during the phase of organisation building. Arvind Kejriwal, AAP’s founder and Delhi CM, did not have the patience for this. To keep the momentum going, the AAP adopted a confrontationist stand, especially in Delhi, where it was always at loggerheads with the lieutenant governor. It consistently projected itself as an anti-establishment party, raking up various issues of corruption in high places. In the process it won more enemies than friends. In a bid to expand rapidly, it did not focus adequately on governance of Delhi, its home ground. Some of the measures that it undertook including the odd-even number traffic rationalisation scheme to control pollution and grading of Delhi schools were not adequately thought through. The manner in which it handled the dengue outbreak last year also left much to be desired.

Once on the downside, AAP fell back on traditional strategies of mobilisation: publicity mongering, allegations of corruption in high places, advertising and blame game. The more the AAP relied on the traditional methods, the more it distanced itself from its middle class support base that had brought it to power and went against the very grain of its creation.

Despite its missteps and irrespective of its failure, what the AAP experiment shows is that there is enough space for alternative politics based on the principles and probity in public life. Indians are yearning for principled politics. Any political formation that taps this yearning is in all probability likely to be suitably rewarded. The mainstream parties, particularly the BJP, have been quick to learn these lessons. The BJP successfully scripted a narrative on the issues of corruption and black money during demonetisation. And despite the failure of demonetisation to achieve its originally stated objective, the support for the BJP has not diminished. The BJP’s success in the Uttar Pradesh election amply demonstrates this.

Secondly, the AAP has validated the disjuncture between political parties and people’s movement. Political parties remain relevant only as long as their connect with the people remains strong. Historically, the Congress’s dominance till 1967 was largely on account of its connect with the masses. The Janata Party, which came to power with a huge mandate in 1977, was also born out of a movement. Elsewhere in the world too, movement-based parties have enjoyed considerable mass support. However, it is the party organisation that channelises the movement into the political system. The organisation structure of political parties is of great importance in this regard. They have to be sufficiently open to accommodate people’s interest and sufficiently disciplined to sieve and articulate them. Most political parties in India have failed to nurture their links with the people through organised formal structures. Often they have been reduced to personal fiefdoms, with no inner party democracy and high command culture, which do not resonate the demands of their workers.

The AAP is a reminder to the mainstream parties to renew their ties with the masses, restructure their organisation and build leadership or else face the consequences. AAP’s stint with power and its failure may just the beginning of an unfolding political process or the end of a political formation. Whatever it may be, one is reminded of the dialogue of a popular Bollywood movie: “Picture abhi baaki hai (the story is yet to unfold)”.

Manisha is associate professor, Political Science, SNDT Women’s University.

(The column appears in the June 1-15, 2017 issue of Governance Now)