PM is nervous and on back-foot. Here is why

In October, during yet another of his visits to Gujarat, prime minister Narendra Modi inaugurated a curious range of projects in Vadodara: a transport hub and multi-level parking facility as well as a waste-to-energy plant of the municipal corporation. If there were no elections coming closer, it would have been the mayor who would’ve cut the ribbon. This, amid a rush of launching several other projects (‘dedicating to the nation’ the campus of IIT Gandhinagar, which was established in 2008) and making several populist moves (raising MSP) ahead of the delayed announcement of the elections. Not that it ended with the election commission’s official announcement: many have given credit to Gujarat polls for the November 10 GST reset.

Does this betray a certain nervousness on the part of the PM?

Understandably, it is critical for the PM to deliver victory in his home state before he seeks national mandate again. But then this is Modi’s home ground. His oratory can be even more persuasive in his mother tongue. And for the first time, he will be seeking votes as PM. His popularity too can be expected to be higher in Gujarat than elsewhere. If he and BJP president Amit Shah can lead the party to historic wins in far more challenging states like Uttar Pradesh, they should face no difficulty in Gujarat. More so, considering that the party has been in power since 1995 (with a small break) and has grown deep organisational roots, whereas the Congress is in disarray. Indeed, a few months ago, it seemed that Modi as PM would fetch more seats that Modi as CM ever did.

Against this background, it is rather surprising to see the BJP on the back-foot. The story of BJP in Gujarat since the mid-1980s has always been an upward chart, not counting a couple of quite minor setbacks. The story of Modi since 2001 is no different. Then what would account for this nervousness all of a sudden?

Is it that these are the first state elections after Modi left Gandhinagar? That is partly a factor: his successors lack his crisis management skills; otherwise several caste-based agitations might not have found widespread support (just as they had not when Modi was CM). Also, his successors may not have been able to make the bureaucracy deliver efficiently.

Are the three young caste campaigners a factor? No, they have been around for a year or two, and the ruling party must have discounted whatever impact they can make. Yes, thanks to them, caste has surfaced as an issue in Gujarat. All these years, on the face of it, caste was not a factor in Gujarat, because it was successfully subsumed under Hindutva and ‘development’ – though it did matter very much in candidate selection.

Again, the campaign which claims that “development has gone crazy” is not a factor in itself, though it is a rather unusual development. All these years, social media was the BJP’s own playground; making fun of the Congress and the Family and so on, and getting good traction from people. But when Amit Shah has to tell his party cadres to be alert and active on social media and not to fall prey to anti-BJP propaganda, something has changed.

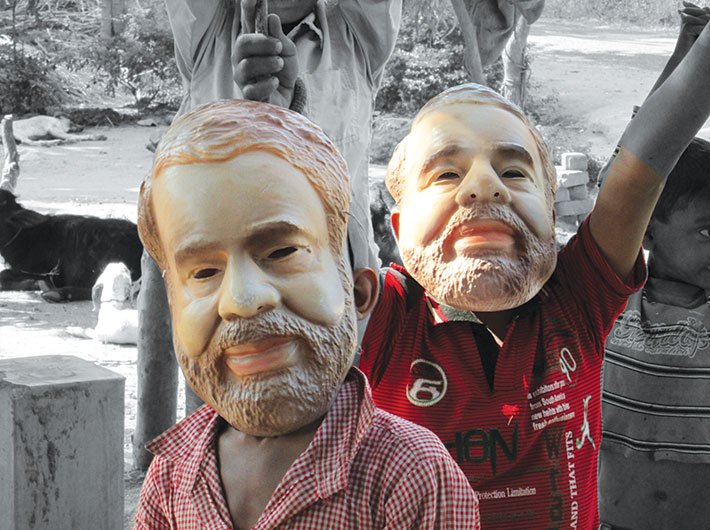

Next in the list of non-factors is Rahul Gandhi. He is interacting with people rather than making speeches. There are reports that he is eliciting a warm response. But his strengths are limited. He is not offering a new narrative – and even resorting to the old Congress tactic of soft religious appeal to Hindus. Rahul is going to temples more frequently than a typical religious-minded person would and he seems in hurry to tick off all major pilgrimage spots in the state in a matter of two months, whereas the devout Gujarati Hindu usually takes years to achieve the feat. Rahul himself, as of today, does not spell a serious threat to the BJP.

The only factor that explains the BJP’s nervousness is a vague resentment, especially among the urban middle class – the BJP’s core constituency – about the central government’s economy management. These are the people who happily supported demonetisation, giving the PM more than the 60 days that he had demanded to set everything right. These are the people who celebrated the one-nation-one-tax moment though they had several questions about the complicated procedures of GST. But as the GDP growth rate went down for six quarters in a row (nearly half of Modi’s term so far), reaching 5.7 percent, their faith in the leadership is shaking. Jobs are scarce, credit growth is not picking up, new investments have not happened. And even the government has stopped claiming that ‘Achchhe Din’ are just round the corner. It too has finally acknowledged that the economy is indeed in a bad shape.

People – anywhere and anytime – do usually have a vague resentment and dissatisfaction with the government of the day. Modi in any case is facing a three-year itch suffered by many of his predecessors. But in Gujarat, he is in a peculiar spot. Over the past decades, as BJP consolidated its base in the state, it made good use of this general resentment because there was a central government run by somebody else. The exception was 2004, when the NDA government’s term ended. Modi was a supremely popular leader in Gujarat and he led the BJP campaign in the state. Yet, the results were near fifty-fifty: 14 seats to BJP and 12 to Congress. Because with BJP ruling in Delhi as well as in Gandhinagar, where do you deflect people’s routine resentment and daily discontent?

The assembly elections in December come with the same context: BJP in Delhi, BJP in Gandhinagar. This is when floating voters can go against Modi, just as they helped him in 2014.

Two decades of near-continous rule means BJP in Gujarat is like the Congress at the national level. BJP in Delhi can blame the “60 years of Congress rule” for any ill, but in Gujarat, the last time Congress ruled was 1995: a significant portion of voters have no memory of that.

Yet, the BJP saga in the state is not likely to end soon. For one, the Modi-Shah duo can be banked upon to deliver in the crux game. Two, they have the organizational advantage, which is the decider in close contests. Three, being in power also gives an upper hand. Four, though people have always thrown up most unpredictable alternatives, but for Gujarat and for now, the ‘there is no alternative’ (TINA) factor is very much valid, given the faces on the other side. And lastly, faced with fragmented Hindu votes, expect a dash of saffron to take them to the finish line.

ashishm@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the November 30, 2017 issue)